Moroccan-French artist Sara Ouhaddou’s work is rooted in long-term collaboration with Moroccan artisans and a sustained exploration of craft as both a cultural language and a tool for empowerment. Through projects that merge material research, fieldwork, and abstract visual systems, Ouhaddou repositions craft not as a passive inheritance, but as a dynamic, living archive. Her works Bahija Idriss – Atchana, 2023, in Arabic( بهيجة إدريس ,عطشانة), and Partition I, 2023 exemplify her commitment to collaborative making, regional knowledge, and the reclamation of aesthetic traditions often excluded from dominant narratives of art history.

Craft, for Ouhaddou, is not merely a technique or decorative tradition. It is a mode of thinking and producing that engages with questions of geography, labor, and cultural resilience. Since 2013, she has developed workshops with artisans across Morocco, from ceramicists in the Ourika Valley to glassmakers in urban medinas. These partnerships are grounded in mutual learning and experimentation, creating what she describes as "spaces of emancipation." They resist the pressures of global art markets by prioritizing community-based creativity and sustainable collaboration rooted in local knowledge.

Bahija Idriss – Atchana reflects Ouhaddou’s material sensitivity and collaborative ethos. The piece combines cedar wood, various types of traditionally stained glass (Iraqi, and Moorish), brass, and copper. These materials carry historical and symbolic weight, evoking Moroccan architecture, artisanal heritage, and a deep tactile intimacy with craft traditions. The work is a nod to Bahija Idriss, a beloved Moroccan singer of the mid-20th century, and takes its title from one of Bahija Idriss’s songs, Atchana (thirsty), which evokes emotional yearning.

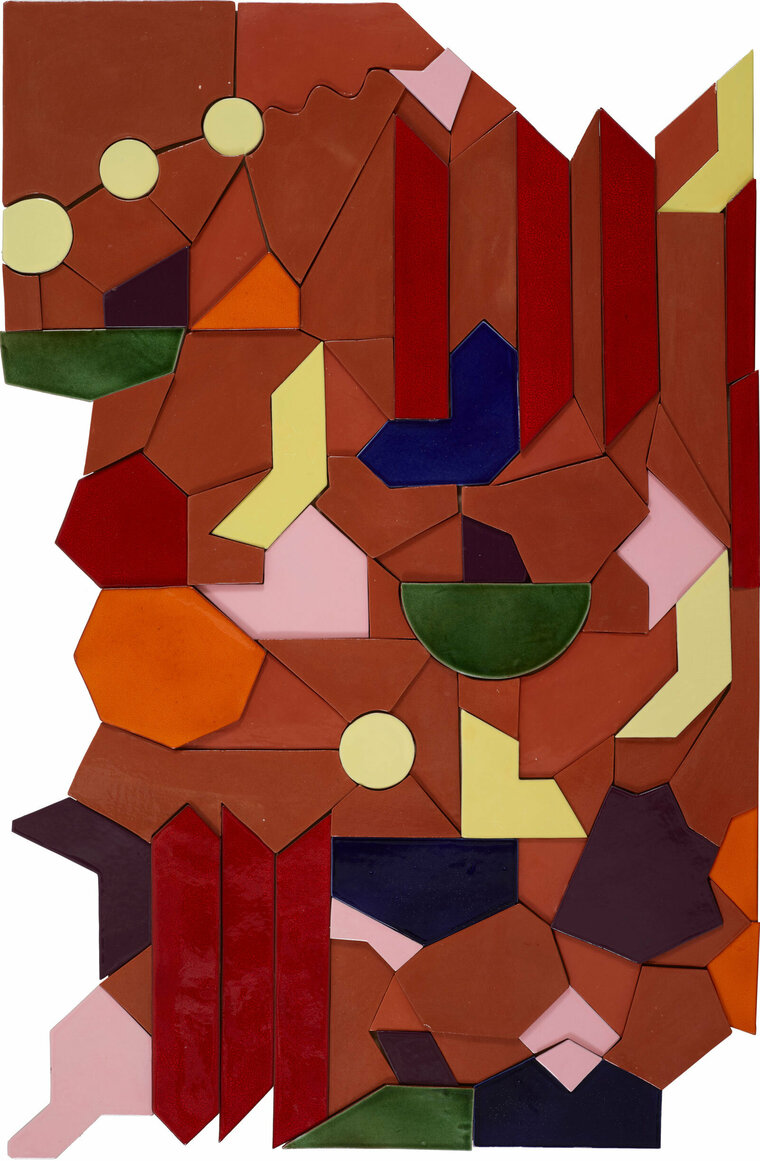

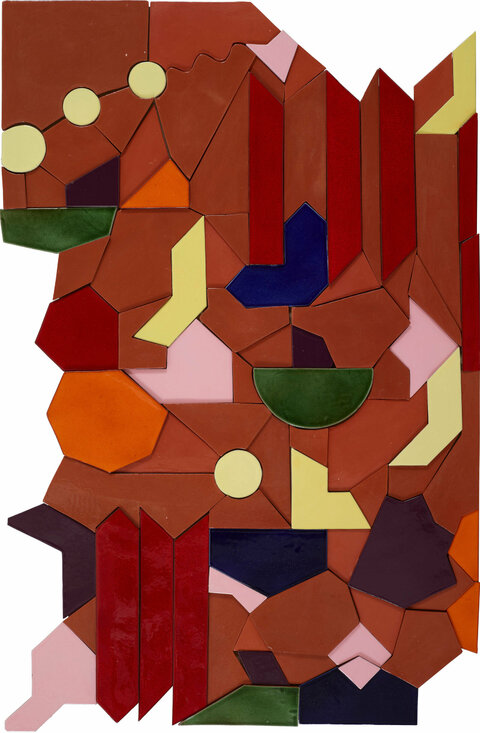

Partition I also emerges from Ouhaddou’s commitment to collaboration, material exploration, and the layered presence of language. While one is titled after a song and the other remains more enigmatic, both works are anchored in artisanal practices and constructed through close dialogue with Moroccan craftspeople. In Partition I, hand-sculpted ceramic and glazes reflect methods drawn from rural ceramic communities, just as Atchana integrates traditional glasswork and carpentry.

Both works are shaped by Ouhaddou’s ongoing interest in the Arabic alphabet. Since 2015, she has been developing a new font made up of abstract, geometric versions of Arabic letters. These forms do not appear clearly in the works, but they influence how she builds patterns and shapes. This changing, unreadable script reflects Ouhaddou’s view of craft as something alive, always evolving, and passed between generations. In both pieces, language is not always visible, but it is present, quietly guiding the structure and linking the works to ideas of memory, heritage, and reinterpretation.

Ouhaddou’s practice is significant not only for its aesthetic outcomes but for what it proposes institutionally and ethically. By embedding collaboration into her methodology, she redefines the boundaries of contemporary art. Her work challenges hierarchies between artist and artisan, fine art and craft, concept and technique. In doing so, she brings renewed attention to the value of knowledge systems that are often marginalized, particularly those rooted in women’s labor, regional traditions, and oral transmission.