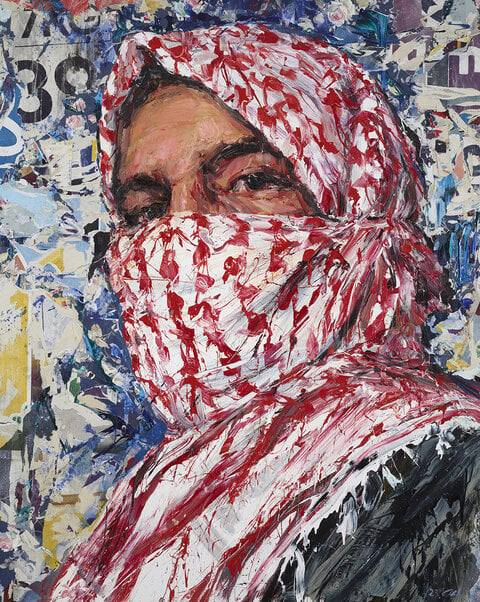

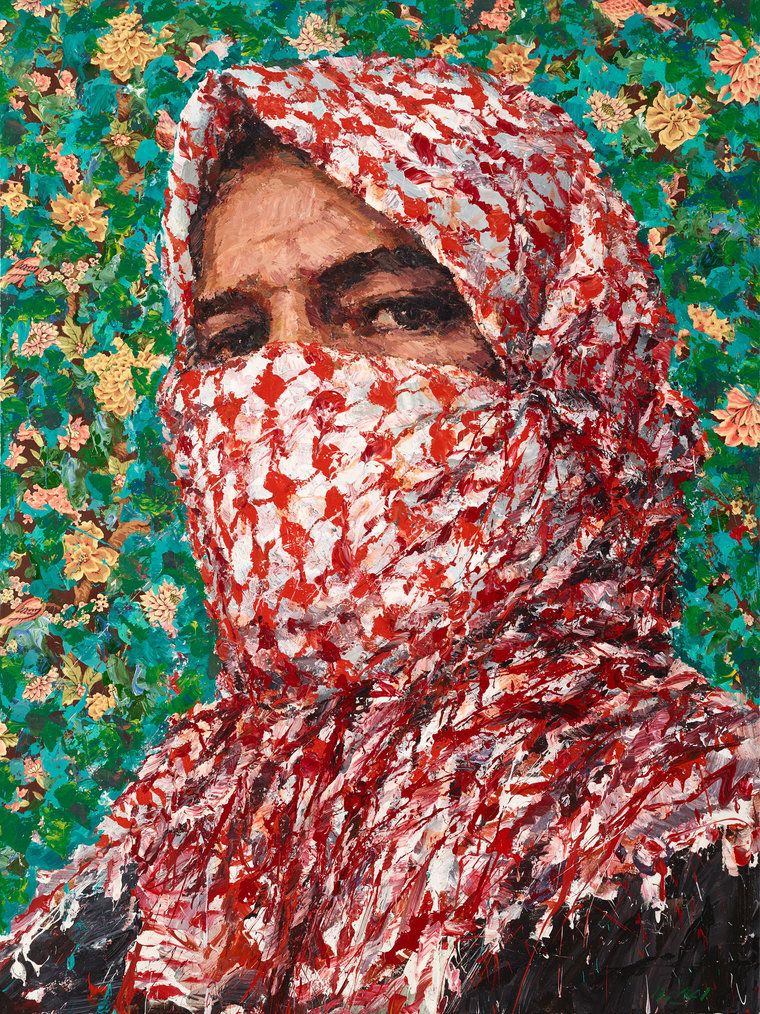

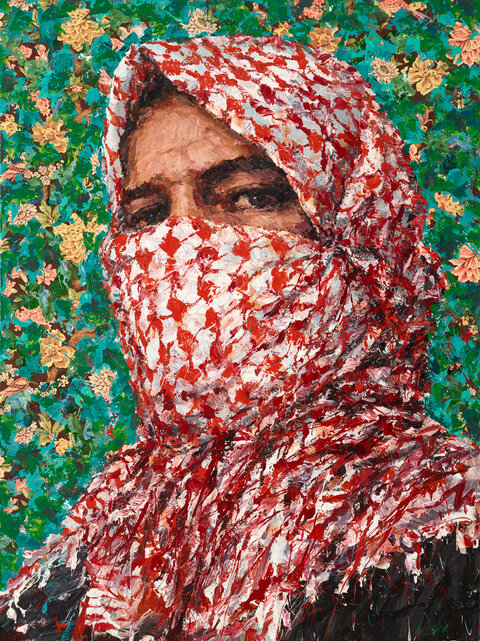

In one of his most celebrated and controversial sequence of portraiture known as

al-Mulatham (the masked), 2013, Ayman Baalbaki experiments with the

often-contradictory themes of anonymity and visibility. This large-scale painting, in

acrylic on fabric laid on canvas, features one gigantic bust view portrait of a fida’i (a

freedom fighter) against a vibrant flowery background. The head and face are

obscured in a white and red checkered keffiyeh, and only the shadowed sharp eyes

are spared.

Though stunning in its animated patterns and bright colors, the portrait echoes uncertainty and disillusionment. As part of a series of works, Baalbaki explains that these portraits “incarnate both hope and despair.” He also adds, “in every portrait, I seek to offer a different interpretation and a new way of reading.” Curiously, author Michel Fani perceives Al-Mulatham as Baalbaki’s self-portrait in the guise of a fida’i. The word fida’i is usually associated with Palestinian freedom fighters. However, it generally translates to “the one who sacrifices himself” and is associated with Christ as savior. Therefore, the fida’i can be anyone seeking redemption or salvation.

In Al-Mulatham, Baalbaki examines the keffiyeh as an iconographic symbol. The keffiyeh, a white square cotton scarf checkered in black or red, was initially used as a traditional headdress and soon evolved into a glorified symbol of the Palestinian resistance. In the west, it has become a symbol of Islamist extremists. However, for Baalbaki, Al-Mulatham is neither a glorified symbol nor a symbol of terror. Though Baalbaki’s keffiyeh is imposing, it is painted with frenzied red and white brush strokes. The fida’i holds no weapons and is drawn against a ‘kitschy’ background, insinuating how Al-Mulatham is a complex and often misread masked hero.

.jpg)

.jpg)