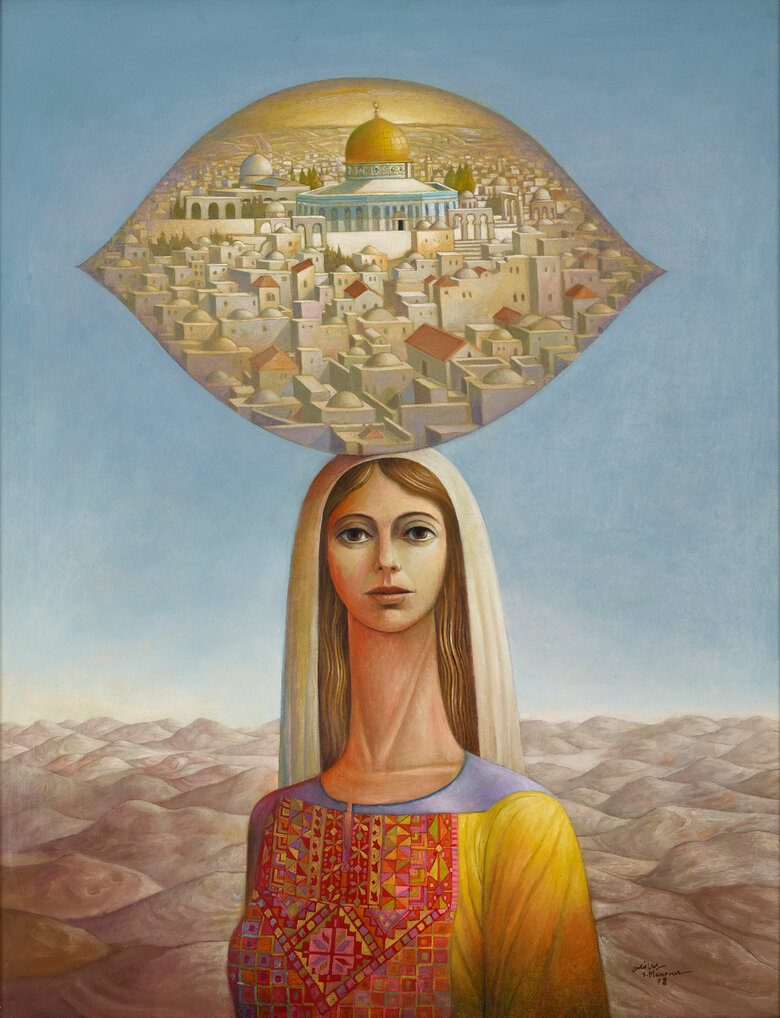

Sliman Anis Mansour's seminal painting, Jamal al Mahamel III, 2005, also known as The Camel/Carrier of Hardships, 2005, is titled by the famous Palestinian poet Emile Habibi. The term ‘camel’ is used because it is a symbol of patience and endurance, which is poignant as the main theme this painting explores is that of exile within Palestine. Burdened by longing and loss, a fatigued old porter is shown carrying Jerusalem on his back from within an endless void. The sky is painted with soft, interrupted brushstrokes of diluted blue, grey, and yellow acrylic paint. The painting's solemn vision is accentuated through the matte and smooth effect of this paint, which intensifies the oppressiveness of the expansive light blue and gray surrounding. The bright red of the scarf in the middle of the painting simultaneously breaks the monotony and keeps it from further diluting.

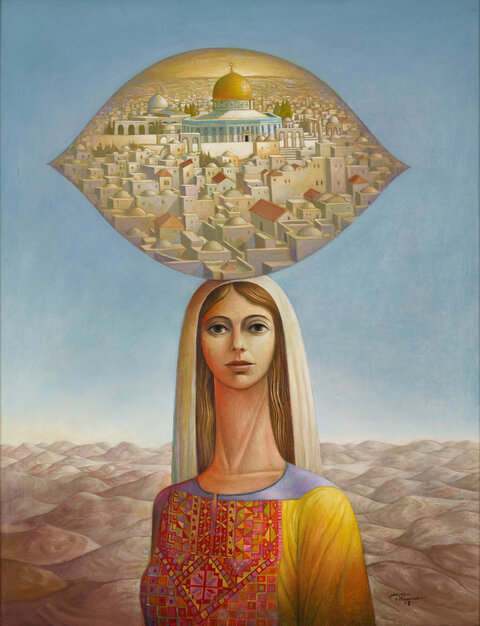

The painting is both surreal and hyperreal. The surreal characteristics are demonstrated in the way Jerusalem is depicted. It is engulfed within a huge eye, which symbolizes a portal between the inner, subjective self and the external world. Through this eye, Mansour disrupts complacency and invites the viewer to explore a new reality where Jerusalem is rendered as a paradise lost or an idealistic safe haven that is untouched and untainted by conflict and warfare.

The artist has chosen to locate the horizon line at a low level, emphasizing a vast and dramatic sky, and making the subject, the porter, appear larger and more significant. This creates a worm's-eye view perspective, lending the image a hyperreal visual quality. By doing so, Mansour portrays a reality that is more intense and detailed than life, a "better" version of reality. Additionally, a significant hypereal characteristic is the oversized extremities of the porter's legs and hands, which are closely related and symbolic of the burden and hardship that porters bear, as well as the unfair life that workers in society face.

Rooted in heritage and reaffirming the Arab Palestinian identity and sense of belonging, the work echoes the influence of Mexican artist Diego Rivera, who used iconography to represent the working class and their struggles, emphasizing the collective suffering and history embedded in the bodies of people. The Palestinian porter, barefoot and dressed in traditional clothing, his shoulders slumped under the weight, evokes the image of fathers and grandfathers who are similarly muted. The figure carries the burden everywhere, both physically and metaphorically, holding onto the truth while symbolizing the political, cultural, and religious struggles of Palestinians.

This artwork was painted in three versions. One was created in 1973 and has been owned by a London-based collector; another was created in 1975 and was owned by Muammar al-Gaddafi and destroyed during the U.S. bombings of his military base in Tripoli, Libya, in 1986. The third version is Jamal El Mahamel III, which resurfaced at a Christie's auction in 2015, was incorrectly titled Jamal El Mahamel II, as it was believed to be the second version, rather than the third. At the same Christie's evening auction in 2015, the aforementioned London-based collector confirmed his ownership of the first version, created in 1973, and explained that the 1975 version was destroyed, and the one in the auction should be considered the third version. Christie's cleared its authentication with the artist himself, and the late Dr. Ramzi Dalloul acquired it during that 2015 auction. It is now part of the Dalloul Art Foundation collection. The Jamal al Mahamel III, 2005 version is larger and brighter than the two before it. Jerusalem, the city, is now depicted with the Dome of the Rock and its crescent atop it, and a church facing it with a cross clearly painted on top. The skyline symbolizes holiness for Muslims, Christians, and Jews. During the re-creation of Jamal El Mahamel III in 2005, workers informed the artist that he should have depicted the rope on the porter's head as flat, rather than a braided rope like the one shown in versions one and two. They explained that porters use flat ropes to carry boxes or goods on their heads; this correction was incorporated into the third version in 2005.

This painting, along with many others by Mansour, was reproduced as posters or postcards for ease of acquisition and circulation. This allowed the artists and their work to both serve the cause and preserve the visual history. Reproduction of such artworks in print was especially crucial for Palestinian artists at the time because there were virtually no permanent galleries or art centers in occupied Palestine until the mid-1990s.

Instead of creating art solely in the service of national political movements, works like Mansour's stressed the dissolution of life by removing clear horizon lines and abstracting landscapes. Here, for instance, Mansour illustrated Jerusalem as a glowing, utopian city with meticulous architecture, and the Dome of the Rock disproportionately large behind the porter's head. This idealistic scene is held together within the contours of an eye-shaped space. At the same time, the porter's face lacks the details of defined features, especially in his eyes. Instead, what he carries on his tired back is what his eyes really see – a sight larger than life, too large to fit within the old man's sunken face.

Signed in Arabic and English on the lower right front

_SuleimanAnisMansour_Front.jpg)