Although modern-day Saudi Arabia is often associated with oil wealth and rapid urban growth, its artistic heritage dates back millennia, rooted in a profound connection to the landscape and local customs. The Arabian Peninsula has a rich history of artistic practices, with ancient rock paintings dating back thousands of years.[1]

These paintings, depicting animals and humans, often held symbolic meanings tied to the beliefs of the time.[2]

Female figures across these works were frequently depicted as large, possibly reflecting their social status or roles in religious worship, with some scenes suggesting women's involvement in war, marriage, and birth.[3]

Before Islam, cities such as al-Faw[4] showcased art through sculptures and murals.[5] For instance, murals from the 1st century CE in al-Faw depicted women of high social standing, highlighting their importance and the societal structures of that time.[6]

With the advent of Islam, art shifted away from painting and sculpture – due to their ties to pre-Islamic paganism – towards architecture, applied arts, and Arabic calligraphy.[7] Women contributed to these arts through traditional crafts such as prayer rugs, henna designs, and tent weaving – women from Aseer, for example, were known for their wall decorations,[8] which has been listed on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list.[9] Society across the Arabian Peninsula was predominantly based on trade and, as such, craftsmanship was especially valued with artisans regarded as artists in their own right.[10]

Over the past century, Saudi Arabia’s art scene has undergone a remarkable transformation, mirroring the nation’s shifting cultural and political dynamics.[11] The evolution of Saudi art and education was influenced by sociopolitical changes throughout various phases – from early government initiatives to the conservatism of the Sahwa period, and finally to the progressive ambitions of Vision 2030.[12] Each phase of the Kingdom’s history has left its mark on the development of Saudi art. This evolution has provided both challenges and opportunities for artists, shaping the narratives that define their work. The following exploration highlights the historical and cultural backdrop that continues to shape Saudi Arabia’s artistic landscape.

General Overview of Saudi Arabia and Education

The territory that comprises the modern-day Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is largely made up of four major regions: the Hejaz, Najd, and the eastern and southern areas. Before the establishment of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932, these regions experienced a series of political and social transformations. In the early 18th century, the Al Saud family, under the leadership of Muhammad (Ibin Saud Al Muqrin) Al Saud, Emir of Diryah, known mononymously as (Ibn Saud)[13], formed an alliance with the religious reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. This partnership led to the creation of the Emirate of Diriyah (in Najd) in 1727, marking the rise of the First Saudi State. The state expanded rapidly, encompassing much of present-day Saudi Arabia, and was characterized by the spread of Wahhabism, a strict interpretation of Sunni Islam. However, in 1818, the Ottoman Empire, aiming to suppress the Wahhabi movement, destroyed Diriyah and ended the First Saudi State. The Al Saud family re-established their power in the region by founding the Emirate of Najd in 1824, with Riyadh as its capital. This period, known as the Second Saudi State, was marked by internal conflicts and external pressures.

The early 20th century saw the decline of Ottoman influence in the region, especially after World War I. During this time, King Abdulaziz Al Saud,[14] the eldest son of Muhammad bin Saud Al Muqrin, also known as Ibn Saud, emerged as a significant leader. In 1902, he recaptured Riyadh, initiating a series of military campaigns that led to the unification of various regions under his rule. By 1926, King Ibn Saud had established the Kingdom of Hejaz and Najd, and in 1932, he proclaimed the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, uniting the Arabian Peninsula under a single nation-state.

Education before the 20th century was limited, since neither the Bedouin communities nor those in the cities had much access to it.[15] King Ibn Saud’s reign from 1932 till 1953 focused primarily on establishing the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and laying its foundational infrastructure.[16] His efforts centered on consolidating various regions under one centralized government while maintaining the authority of the Saudi royal family, a process that included balancing political control with the legitimacy provided by Wahhabi Sunni Islam.[17] During this period, official public education began in 1925, and was primarily religious in nature with public schooling only available for boys while girls were taught at home.[18] Traditional crafts were passed down within families,[19] and there were no formal institutions that provided opportunities for public discourse between the government and its people.[20]

Regarding art education, King Abdulaziz Al Saud’s reign saw limited institutionalized programs, and art was largely confined to traditional handicrafts and manual skills.[21] However, there were several minor, but important, steps that marked this period. For instance, in 1908, drawing materials (a phrase used to indicate art education) were included in the study plan at a charity school in Makkah, marking one of the earliest occurrences of formal art instruction.[22] By 1925, traditional crafts were being taught in schools of Islamic sciences in Medina with drawing included for students in the third and fourth grades.[23] The Ministry of Education (named Almaref) was established in 1936, and the teaching of drawing in weekly high school classes was approved.[24] The study of painting began in elementary schools in 1929, and was then expanded to middle and secondary schools in 1944.[25] For a period of time after 1944, the study of painting as a school subject was canceled for religious reasons, with Arabic calligraphy and handicrafts becoming part of extracurricular activities.[26] However, since many Saudis were being sent abroad to specialize in fields such as architectural engineering, medicine, and fine arts, these subjects were reincorporated into schooling and developed further in 1953.[27] Motivated by religious beliefs, there was initial opposition to teaching Western arts such as drawing, viewed as incompatible with Islam. Overall, this era was defined by a conservative approach that prioritized stability over cultural diversification.

Between 1953 and 1964, under the reign of King Abdulaziz’s son, King Saud bin Abdulaziz,[28] Saudi Arabia underwent significant economic and cultural changes. In terms of education, previously, the emphasis had primarily been on educating male students, making the opening of the first girls’ school in 1955 a significant milestone.[29] A more concrete step that marked the beginning of art education was in 1957, when the first curriculum plan was approved which included art.[30] Art education as a school subject for high schoolers was called “decoration”, and in 1959 King Saud opened the first art exhibition in school.[31] That same year, the subject of “Arts and Crafts” was available as part of public education for girls with “the aim […] to train the students in manual skills in the use and formation of raw materials in order to familiarize the students with patience, perseverance, and self-confidence.”[32] After receiving formal accreditation in 1962, the subject was formally renamed into “Art Education” so it could encompass the wider range of visual arts as they evolve, and in order to compete with neighboring countries.[33] During this period, oil production soared, yielding revenues that climbed from $7 million to $200 million and spurring the establishment of the National Commercial Bank in 1953—marking the start of the Kingdom’s financial system.[34] However, this period was also marked by limited effective economic planning, resulting in lavish spending, deficits, and foreign borrowing.[35] Meanwhile, cultural life blossomed, particularly along the western coast, with the rise of new radio stations, schools, universities, and newspapers.[36]

When King Faisal bin Abdulaziz bin Abdulrahman[37] came to power, 1964 till 1975,[38] his approach to education, both broadly and specifically in the realm of art, showed a considerable shift from the policies of his predecessors. His wife Queen Iffat bint Mohammad Al Thunayan was known as a pioneer and activist for women's education. She founded the first women’s academy Dar al Hanan to raise good mothers and wives.

King Faisal’s reign was defined by a dramatic increase in oil revenues, which fueled rapid economic growth and social development. His policies focused on infrastructure expansion, the formalization of state planning, and the improvement of social services, particularly in education and healthcare, while also consolidating the state through an expanded bureaucracy and the shift from royal gifts to institutionalized salaries.[39] King Faisal’s first priority was consolidating the state apparatus and modernizing the country’s institutions, especially the educational system. However, society remained deeply conservative, with social norms reflecting a commitment to traditional Islamic values.

King Faisal’s vision was to ensure that Saudi Arabia could thrive economically, politically, and culturally in a rapidly changing world. Under his rule, the Saudi government dedicated a significant portion of oil revenues to building new schools and improving existing ones. Within this context, the government’s investment in the arts created a controlled environment for cultural exploration. Artists were encouraged and directed to focus on themes that aligned with Saudi national identity, such as heritage, Islamic values, and the nation’s rapid transformation, which were seen as central to fostering a unified cultural narrative.[40] Furthermore, during this period, students were sent abroad to study, bringing back much needed new knowledge and expertise.[41] Scholarships were also provided to students to study art abroad in cultural hubs such as Cairo, Rome, Florence, and the United States.[42] These opportunities enabled a generation of artists to gain exposure to global art movements and return with new techniques and ideas. Notable artists who benefited include Abdulhalim Radwi,[43] who earned his BA from the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome in 1964, and Mohammed Al-Saleem, who studied at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze in the early 1970s.[44] Upon returning, these artists became educators and pioneers, significantly contributing to the Kingdom's artistic development.

King Faisal also sought to expand educational opportunities for girls and women, while remaining within the parameters of the principles of Sharia.[45] Unlike the early years of King Saud's reign, King Faisal's era saw the development of more structured guidelines for art education. Policies of this era showed a greater willingness to integrate modern ideas and practices while still adhering to cultural values. This period saw more significant steps towards institutionalizing girls’ education, with the establishment of girls’ public schools in 1960.[46] This was met with resistance from religious and conservative segments of Saudi society. In response, and in order to pacify the dissident voices, King Faisal established a separate educational institution for girls, the Department of Religious Guidance, which the Mufti was head and director of, unlike the boys whose education was controlled by the Ministry of Education.[47]

A significant turning point came with the establishment of the Institute of Art Education in Riyadh in 1965, which marked the kingdom’s growing commitment to cultural and artistic development.[48] Building on this foundation, the Ministry of Education played a central role, integrating art programs into public schools and universities, and establishing art departments in higher education institutions to train future art teachers, and in order to cultivate awareness of art expression and research.[49] During this period, Saudi artist Safeya Binzagr (b. 1940), a pioneer of the kingdom’s fine arts movement, made history in 1968 when, alongside her friend Mounirah Mosly, she held an exhibition at the Dar Al Tarbiya girls’ school.[50] This event marked a groundbreaking moment, as she became one of only two female artists to ever showcase their work in the country at the time.[51] Furthermore, in 1995, she founded Darat Safeya Binzagr, a private cultural center that houses her artwork, cultural collection, studio, and an art and literature library, which also held arts exhibitions to promote student and faculty engagement with the arts.[52]

During the 1970s, public art schools began integrating classical art that consists of Islamic motifs, clay production, sewing and embroidery.[53] This period also saw the first college for girls being opened, in 1970, in response to a shortage of female teachers, but the only courses offered were related to teaching and basic housekeeping subjects such as cooking.[54] In 1975, a year after the Ministry of Education abolished art education to make room for other subjects, they were forced to reinclude it as part of the curriculum.[55] Initially, during this period, instructors came from Europe, the US, and other Arab nations like Egypt, Iraq, and Sudan.[56] Interestingly, the majority of art colleges in the Kingdom were for women.[57] While these colleges operated under certain constraints, they offered students more artistic license than schools. Women in these college programs could create figurative art and portraits, and experiment with diverse techniques.[58] Despite this increased freedom of expression, students were typically guided to create art that showcased their Saudi and Arab heritage.[59]

The artistic exploration of this era emphasized communal identity and celebrated Saudi Arabia’s cultural heritage.[60] Many modernist artists of the 1960s and 1970s drew inspiration from the natural arid landscapes; Bedouin life, and traditional crafts, incorporating motifs such as desert dunes, oases, tents, camels, and tribal attire; and traditional crafts like weaving, embroidery, and pottery. These elements were blended with modern forms such as abstract compositions, geometric patterns, and contemporary materials, creating a distinctly Saudi expression of art.[61] Their work often focused on themes of national identity and cultural preservation, aligned with the government's vision of fostering a cohesive societal narrative during a time of rapid modernization. King Faisal was seen as a builder and reformer whose rule catapulted the Kingdom’s wealth and respect on a global scale.[62]

After the assassination of King Faisal in 1975, he was succeeded by King Khalid bin Abdulaziz bin Rahman[63] who remained in power till his passing in 1982. The overarching objective of art education during this period was to highlight Islamic heritage as expressed in artwork and decorative elements.[64] In 1977, the Ministry of Education issued the following goals for art education in k12 and college: “emotional growth, intellectual development, physical development, perception, social development, aesthetics, creativity, the use of the senses, respect for and love of work, self expression, self confidence, knowledge of tools, the expansion of knowledge in general and specifically knowledge of the terminology of art, and the ability to take advantage of free time in order to benefit the person and the society.”[65] These goals were reissued in 1988.[66]

Saudi Arabia’s sociocultural landscape shifted notably during the reign of King Khalid. Rapid economic development spurred materialism, creating a stark contrast with the state’s emphasis on Islamic values.[67] External events further shaped this era: the 1979 Iranian Revolution heightened fears about communism and Islamic activism, prompting the kingdom to strengthen ties with the United States.[68] Meanwhile, domestic criticism of perceived government corruption and Western influence culminated in the 1979 siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca[69]. In response, authorities expanded support for religious institutions, introduced more stringent social policies, and intensified security measures.[70] Following the siege and the influence of Iran’s new Islamic regime, Saudi officials worked closely with religious leaders, reinforcing traditional practices and norms. This conservative shift deeply affected cultural and artistic expression, favoring Islamic and traditional art while reducing exposure to contemporary styles. Schools emphasized traditional crafts and nationalistic artwork, reflecting a broader governmental desire to safeguard cultural identity against foreign influences.

In comparison, King Fahd bin Abdulaziz’s[71] reign from 1982 until 2005 was a time of significant economic fluctuations, attempts at limited political reform, and social changes that laid the groundwork for future transformation in Saudi Arabia. King Fahd’s reign preserved Saudi Arabia’s strong Islamic identity and traditional norms – exemplified by his adoption of the title “Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques” in 1986.[72] The kingdom faced economic austerity due to falling oil prices, but remained broadly dedicated to development.[73] However, cultural and educational practices continued to be shaped by conservative views, with women’s roles sparking debate and reforms that advanced their education but left many restrictions firmly in place.[74]

In the 1980s, art education in Saudi Arabia began to expand with the establishment of bachelor’s degree programs in art education at King Saud University (1975) and Umm Al-Qura University (1977).[75] During that period, 52 humanities colleges had been opened, with five offering art education programs. These universities primarily focused on four specializations: ceramics, textiles, metals, and printing.[76] The curricula were largely standardized and have remained largely unchanged, with minor updates over the years. The development of these programs marked a significant step in formalizing art education, as students were required to undergo practical training in teaching art in public schools, alongside their academic studies.[77]

When global oil prices plummeted in the 1980s, Saudi Arabia experienced severe economic pressures. Under King Fahd, the government promoted “Saudization,” aiming to reduce reliance on foreign labor.[78] These efforts coincided with growing social divisions between the wealthy elite and marginalized groups that were increasingly conscious of inequality. The Saudi government grappled with a growing wave of discontent centered on its close alliance with the United States.[79]

Despite these tensions, the kingdom continued to depend on American military cooperation for its security, particularly as a means to counter regional growing powers such as Iran. Yet these policies, along with an expanding Western presence, met with mounting criticism among Saudis who saw Western influence as a source of moral and social corruption. Non-governmental religious organizations and a younger generation of self-appointed religious enforcers gained prominence by calling for greater Islamic “authenticity” and criticizing Western encroachment.[80]

Debates over the balance between Islamic values and modernization flourished, reflecting rising skepticism about the kingdom’s close alliance with the United States.[81]

The heightened conservatism of this era had a notable impact on society[82] and on the arts. While educational institutions emphasized traditional and Islamic art forms, some contemporary artists ventured to use their work as vehicles for social critique. However, the space for such expressions remained limited due to a climate shaped by religious conservatism and apprehension over Western cultural influence.

The Impact of the Sahwa (Post-1979 Islamic Awakening)

The 1979 Islamic Revolution[83] in Iran marked a turning point for many societies in the Middle East, and Saudi Arabia was no exception.[84] While Saudi Arabia was already deeply rooted in Islamic principles, the Revolution acted as a catalyst for the kingdom to reinforce its religious identity amidst fears of ideological influence from Shi’a Iran. In response, Saudi Arabia underwent a significant shift toward conservatism in a movement known as the Sahwa or Islamic Awakening.[85] The Sahwa brought about a heightened emphasis on religious adherence, reshaping public and private life in Saudi Arabia to align more closely with conservative Sunni Islamic values. The Saudi society of the 1960s and early 1970s was more permissive, with artistic and cultural activities flourishing alongside modernization efforts. However, the post-1979 era marked a sharp departure as the kingdom sought to counteract external influences and reassert its religious authority in the Islamic world.

During the late 1970s and 1980s, the Sahwa (“Islamic Awakening”) movement gained momentum in Saudi Arabia, profoundly reshaping social and cultural norms – particularly in relation to women’s roles and public visibility. While the Saudi government had previously expanded educational opportunities for women in the 1960s and 1970s as part of a broader modernization effort, it began reversing these policies in the 1980s to reinforce its religious credentials.[86] In partnership with religious scholars (ulama), the state imposed greater restrictions that curtailed women’s freedoms and heightened their surveillance in public spaces.[87] This shift was accelerated by events such as the 1979 Grand Mosque siege, where the underlying demands and critiques pushed the government to adopt more conservative policies as a conciliatory way to quell radical Islamist sentiment and maintain itself as the guardian of Islamic identity.[88]

New guidelines limited state scholarships available to women pursuing studies overseas. and fatwas (religious rulings) further restricted women’s public roles.[89] Increased scrutiny from both the government and religious authorities led to tighter enforcement of gender segregation and the requirement that women be accompanied by a male guardian (mahram) when traveling.[90] This policy not only impeded women’s mobility but also hindered their ability to pursue higher education outside the kingdom. Additionally, women were prohibited from marrying non-Saudis without special permission, reflecting the growing emphasis on preserving what was viewed as a more “authentic” Saudi Islamic identity.[91] As a result, women became a focal point in the broader ideological struggle, with competing actors – state authorities, religious scholars, and conservative factions – vying to define and control their roles.[92]

These developments represented a significant reversal of earlier trends. Despite initial resistance from some in the religious establishment, the state had previously championed women’s education as part of its modernization and nation-building initiatives. In the 1960s, the government even entrusted girls’ education to religious scholars in order to overcome opposition at the time. By the 1980s, however, the state used its alliances with conservative clerics to enforce stricter regulations on women’s social participation and educational pursuits, underscoring a broader strategy of “Islamization” meant to consolidate political legitimacy and counteract perceived threats from both radical Islamists and Western influences.[93] The new framework left women primarily in roles aligned with the nation’s vision of piety, thus narrowing the scope of their public and professional engagement.[94]

This period saw the rise of the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice (CPVPV), often referred to as the religious police, whose authority extended into nearly every aspect of daily life. Under the CPVPV’s influence, public spaces became heavily regulated, and religious policing was used to enforce dress codes, gender segregation, and restricted social interactions. The arts were among the sectors most affected by the Sahwa’s conservative turn. Creative expression was confined to boundaries that adhered to strict interpretations of Islamic principles and a preference for geometric and floral motifs inspired by Islamic art,[95] and limitations on performances or exhibitions that could be perceived as un-Islamic.

Cultural institutions such as the Ministry of Culture and Information, responsible for regulating media and cultural policies, and the King Fahd Cultural Center, which served as a hub for artistic and cultural events, faced increased scrutiny during this period.[96] These restrictions were primarily enforced by the government, which acted under the influence of the CPVPV to ensure compliance with the Sahwa’s conservative agenda.[97] This heavy regulation curtailed public artistic expression, leaving many artists to work within private or underground networks to sustain their creative practices.

For women artists, the Sahwa era brought further limitations on visibility and public participation. Even before this period, women faced significant barriers, such as societal expectations that prioritized domestic roles over professional ambitions, and scarce opportunities to participate in public exhibitions.[98] These challenges were compounded as women’s roles were strictly defined, and female artists had limited access to public exhibition spaces, leading many to create art in private without the opportunity to share their work with a broader audience.[99] This restrictive environment stalled the growth of contemporary Saudi art, especially for women, whose work remained largely unseen outside close circles or confined spaces. The constraints on public art and creative freedom persisted through the 1980s and 1990s, only beginning to ease near the early 2000s and 2010s, as the Kingdom’s cultural policies shifted toward greater openness and inclusion.

Post–9/11 Environment: International Pressure and State Reforms

In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, Saudi Arabia came under intense international scrutiny due to its perceived links to religious radicalism. As questions arose about the kingdom’s handling of extremism and its broader social policies, the government faced mounting criticism over the status of women in Saudi society.[100] In response, officials embarked on a series of reforms aimed at both mitigating global concerns and addressing internal demands for change. These initiatives included promoting greater visibility of women in public life, expanding their educational and employment opportunities, and gradually weakening the power of religious authorities over women’s affairs.[101] By adopting the language of progress and modernity, the state signaled a shift in how it approached women’s roles, hoping to portray itself as a champion of emancipation.[102]

Until 2002, women's education at all levels in Saudi Arabia was managed by the Department of Religious Guidance, while boys' education was overseen by the Ministry of Education to ensure women's education aligned with traditional roles of being good wives and mothers.[103] In 2002, following a deadly fire at a girls' school in Mecca that exposed the role of the religious police in preventing firemen from entering, the General Presidency for Girls' Education and the Ministry of Education were merged, in response to public demand.[104] This merger led to significant resistance from conservative scholars who believed women's education should be governed by religious authorities, and it highlighted ongoing dissatisfaction with the state's treatment of women's education, including unsafe school conditions and lower funding compared to male education.[105]

This period of reform opened new channels for women to articulate their views, a departure from earlier eras of more stringent restrictions. Educated women – many holding advanced degrees from abroad – began to use the media, literature, and online platforms to advocate for women’s rights and call out issues such as domestic violence.[106] Simultaneously, the government appointed women to official positions and incorporated them into national dialogues, seeking to showcase their achievements as part of its modernization narrative. For instance, the appointment of a woman for the first time as a Deputy Minister in the Ministry of Education in 2009 was seen as a significant step in the state's efforts to improve women's status and visibility within government institutions.[107] This appointment was part of the broader initiative to promote women's participation in sectors like education and employment, signaling the state's commitment to advancing women's rights, though still within the confines of its broader political strategy.[108]

As women gained prominence, discussions around gender became more visible in the public sphere. The state not only permitted but also encouraged debates on women’s economic participation and social freedoms. This environment created space for liberal and moderate Islamist perspectives to challenge the previously dominant conservative discourse, further weakening the grip of religious radicalism on women’s issues.

Although the post-9/11 era introduced more complex conversations about women’s rights, key continuities remained. Many women still grappled with deeply ingrained patriarchal norms that constrained their day-to-day autonomy. The landscape for women grew more diverse and contested, but it remained defined by structural limitations and ongoing negotiations between reform-minded citizens, conservative religious figures, and the Saudi state.[109]

The period following 2005 in Saudi Arabia is primarily characterized by the reign of King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz[110] from 2005-2015, and the subsequent reign of King Salman bin Abdulaziz[111] from 2015-present. This era has seen significant social, economic, and political shifts, with a notable focus on modernization and reform. Educational scholarships were reintroduced, with both men and women sent abroad on government-funded scholarships, while others enrolled in newly established local institutions and training colleges.[112] Saudi women have increasingly demanded greater participation in the economy and social issues, calling for the removal of restrictions like male guardianship and the driving ban (which was lifted in 2018).[113] While some women defend the current system as protecting tradition, other internal voices and international human rights organizations highlighted the ongoing gender discrimination and lack of autonomy under male guardianship.[114]

During this period, the Saudi government began actively diminishing the authority of religious scholars, especially in social matters where women had traditionally been subject to strict oversight. This shift led to a marked increase in women’s visibility and public participation: they were granted seats on the Consultative Council (Shura Council) in 2011 and allowed to run and vote in municipal elections for the first time.[115] Women also benefited from rapidly expanding internet and satellite television platforms, utilizing these new modes of communication to address a wide range of issues that affected their daily lives.[116] State-controlled media featured women in prominent roles, and businesswomen emerged as regular participants in economic forums. These reforms went hand in hand with new legislation and initiatives to boost women’s economic empowerment.[117] At the same time, liberal and moderate Islamist perspectives gained traction, challenging the older religious discourse on gender.

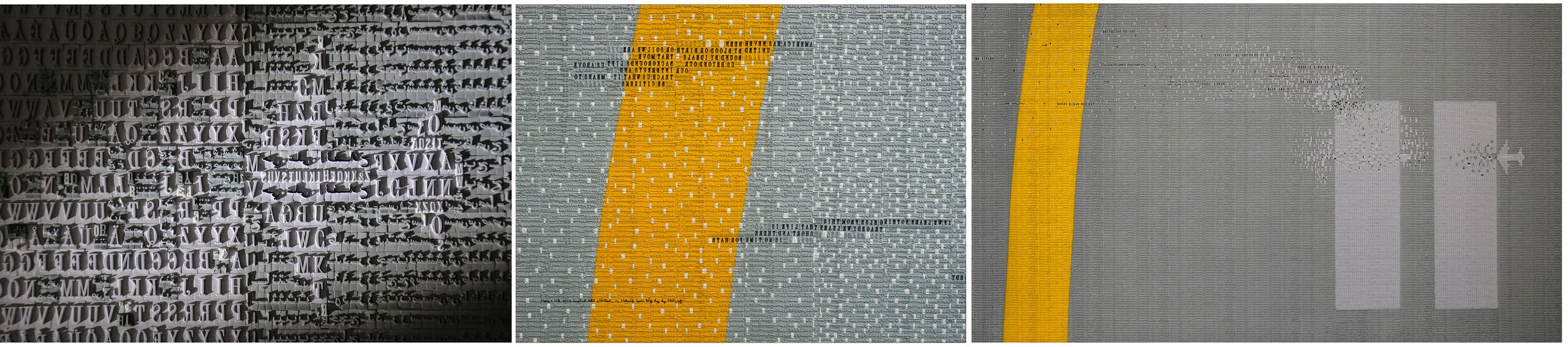

Artists like Maha Malluh (b.1959), a conceptual and mixed-media artist, found subtle ways to critique and document cultural limitations imposed on women in ways that were possibly not as accessible before. For example, in her 2012 series Food for Thought – a collection of large-scale mixed-media installations – Malluh repurposed everyday items, such as used enameled cooking pots, to explore themes of identity and cultural memory. Similarly, in Do You Want to Be Happy, a body of work from the series Food for Thoughts, and part of the Dalloul Art Foundation Collection, Malluh uses a collection of cassette tapes, recordings of hardline instructional religious sermons targeting women, stacked on a wooden tray from old bakeries. These tapes, sourced from local flea markets and junk shops, reflect the cultural transformation caused by the widespread distribution of such cassettes, promoting a new paradigm of thought and a redefined way of life. As Malluh notes, these recordings played a significant role in shaping societal views on women, dictating their behavior, thoughts, and existence to be seen as virtuous. Instead of nurturing their bodies with bread, people were ‘feeding’ their souls with rigid religious sermons, revealing the deep cultural shift within Saudi society. By assembling these blackened, flame-scarred pots and cassette tapes into visual poems, Malluh bridges the past with contemporary narratives, transforming mundane objects into powerful symbols of Saudi heritage and a critique of the restrictive era.

Transformations Across the Art Scene 2000 – present

At the start of the new millennium, art education in Saudi Arabia began to gain traction as part of a broader recognition of art’s importance within society. For instance, schools introduced art education textbooks in 2008, aiming to enhance students' drawing, painting, and design skills; these textbooks cover traditional art techniques, ceramics, calligraphy, weaving, cultural artifacts, and the economic benefits of traditional art.[118] At the colleges level, the number of institutions offering art education for women exceeds those for men, leading many male artists to be self-taught or seek education abroad, which influences their art and its reception in Saudi Arabia, while female artists have more opportunities to attend art colleges domestically.[119]

It's important to note also that while the Ministry of Youth supported the arts, its focus remained on promoting traditional and nationalistic art rather than contemporary or diverse forms.[120]

However, there still remains a clear shift in the development of the arts scene, exemplified by the increasing number of art galleries in Saudi Arabia – around sixty art galleries, mostly privately owned and concentrated in Jeddah.[121] Saudi women have played a leading role in this process: In 2007, Princess Adwa Yazid bin Abdallah Al Saud established the Arts and Skills Institute, Riyadh's first visual arts school, while Neama Al-Sudairy founded Alaan Artspace in 2012, one of Riyadh’s first galleries, which operated until last year.[122] Also in Riyadh, Naila Art Gallery, founded by artist Naifa al-Fayez in 2012, serves as both a gallery and a creative hub, offering workshops, art talks, seminars, and mentoring for emerging artists.[123]

This period saw the rise of prominent artistic collectives that continue to shape the artistic landscape, such as Edge of Arabia, which was founded in 2003 by British artist and entrepreneur Stephen Stapleton, artist Abdulnasser Gharem, previously a military officer, and artist Ahmed Mater, who was an emergency room physician. The movement emerged in response to societal issues. Gharem and Mater, both from the Aseer region, were pivotal members of an earlier artistic collective during the 1990s called Shaziyya (meaning fragmented or shattered), which fostered a new worldview and distinctly Saudi model for creating art, blending local and global influences, addressing cultural and social issues, drawing inspiration from the online world, and establishing a shared social space.[124]

At the start of the new millennia, three significant factors converged to elevate Saudi Arabia’s arts movement onto the global stage: a growing Western curiosity about the Middle East, increased charitable support for the arts within Saudi Arabia, and the emergence of internet technologies that enabled the low-cost promotion of contemporary art.[125] This combination of circumstances created an opportunity for Saudi artists to connect with a broader audience. The name, Edge of Arabia, was inspired by a National Geographic article that depicted Saudi Arabia as being on the "edge" of cultural collapse, which the artists then actively reclaimed to instead reflect the country’s geographical location and the cutting-edge nature of their art.[126] Over the next few years, the trio traveled across Saudi Arabia to recruit artists and patrons to join the movement.[127] Edge of Arabia quickly gained recognition, organizing exhibitions in cities like London, Venice, and Dubai, with its artists’ works being acquired by major institutions such as the British Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum.[128] With a strong international focus, Edge of Arabia has held exhibitions in cities around the world, promoting Saudi art on the global stage and building bridges of understanding between Saudi society and the rest of the world.[129] It has evolved over time, with some members focusing on creating local spaces for dialogue and others working to establish galleries internationally, further cementing Saudi art’s place in the global art scene.[130]

Several women artists, like Arwa al-Neami (Mater’s wife), Sarah Mohanna al-Abdali, and Manal Al Dowayan played a significant role in the Edge of Arabia collective, using their art as a platform for cultural commentary and social change. These artists were integral to the "grassroots journey" that Edge of Arabia founders embarked upon across Saudi Arabia, where they encountered a growing number of women engaged in the art scene, highlighting the important role of female voices in shaping the country's cultural landscape. They defied social norms and engaged with the evolving discourse on gender, identity, and society in Saudi Arabia by contributing powerful pieces that reflected the experiences and challenges of Saudi women.[131] These artists challenged the misconception that Saudi society is inherently opposed to art and modernity, showing that art can be a transformative force for both individual and collective expression as they contributed to a larger narrative of cultural renewal and social progress within the kingdom.[132]

Saudi Arabia’s modernization efforts accelerated, spurred significantly by the announcement of Vision 2030. Vision 2030, announced by Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman (MbS) in 2016, aims to reform Saudi Arabia’s economy and reduce its reliance on oil by fostering economic diversification, with the creative industries playing a key role in the transformation into a knowledge economy. The government recognized the arts as a means to generate economic growth and job opportunities, particularly for young Saudis, while promoting social reform and creating a platform for open dialogue on social and economic issues. As part of the Vision, there is a strong emphasis on developing the cultural and entertainment sector, drawing inspiration from global cultural hubs like London and New York. By integrating the arts into the Vision 2030 plan, the government aims to encourage dialogue and promote a more contemporary, yet culturally grounded, image of Saudi Arabia.

Within this energized landscape, the MiSK Foundation, a nonprofit founded by MbS in 2011, plays a key role in supporting creativity, grassroots cultural production, and cultural exchange by sponsoring art festivals and creating partnerships with media companies.[133] Misk Art Institute (a subsidiary of MiSK), which Ahmed Mater was Founder Director of in 2017-2018,[134] is committed to fostering local artistic talent by offering educational and training opportunities, facilitating collaboration between local and international artists, and providing access to global techniques and trends through its programs and cultural events.[135]

Additionally, fine arts departments were introduced in existing universities like Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University and King Abdulaziz University, providing formal avenues for art education that were previously limited.[136] Furthermore, the establishment of government bodies like the Saudi General Entertainment Authority (GEA) and investments in the film industry aim to foster a vibrant cultural scene and create jobs for young Saudis.[137] Art has also been used as a tool to promote national dialogue on socioeconomic reform, with the government showcasing Saudi artists at high-profile political events to build a positive image of the kingdom. While this support has contributed to the growth of the Saudi arts scene, it has also sparked debate about the independence of artists receiving government funding.[138] Despite this, artists have managed to address sensitive issues and navigate evolving social and cultural norms, using government support to further their careers, address complex social issues, and influence public opinion while working within the system.[139] Contemporary artists of this period have continued to embed cultural symbolism and heritage into their work while engaging with global art movements and addressing broader themes such as globalization, gender, and societal change.[140] This shift reflects a broader dialogue between tradition and the evolving complexities of Saudi society in a more interconnected world.

Major cities like Riyadh, Jeddah, and cultural hubs such as AlUla have hosted numerous exhibitions and festivals. AlUla, a historic region known for its stunning landscapes and ancient archaeological sites, has become a key cultural destination in Saudi Arabia, hosting international art events like Desert X AlUla. For instance, the inaugural Desert X AlUla[141] in 2020 brought international contemporary art to the historic landscapes of AlUla, and the annual Misk Art Week[142] in Riyadh has become a central platform for artists since its launch in 2017. These events reflect a broader cultural shift that invited artists to explore themes previously considered sensitive or taboo, such as gender, identity, and social change.[143]

In tandem with public art initiatives, significant advancements were made in art education and institutional support.[144] Universities across the Kingdom, such as Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University[145] and King Abdulaziz University,[146] began to offer students specialized tracks in disciplines like painting, sculpture, and graphic design. These programs provided formal training opportunities that were previously unavailable. Major museums, including the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture (Ithra)[147] and the Diriyah Biennale Foundation,[148] now serve as essential venues for education, exhibitions, and international collaborations, providing Saudi artists with platforms to gain recognition both locally and globally. Vision 2030’s emphasis on women empowerment has significantly increased opportunities for female artists to participate in public life, study fine arts, and exhibit their work.

Artists like Manal Al Dowayan, a participatory and multimedia artist, and Dana Awartani, a Saudi-Palestinian artist known for her contemporary reinterpretations of traditional Islamic art forms, have gained prominence, presenting their work at major exhibitions both inside and outside the Kingdom. These developments have lifted longstanding barriers on artistic expression, marking the gradual transformation of Saudi identity towards embracing both tradition and progressive values. By embedding arts and culture into the national framework, the kingdom has laid the foundation for a vibrant and more inclusive creative ecosystem.

Al Dowayan’s work, which speaks to the experiences of Saudi women navigating societal expectations, aligns with the spirit of Vision 2030’s transformation.[149] Through her large-scale installations such as Suspended Together, 2011, which features fiberglass doves bearing copies of women’s travel permits, Al Dowayan critiques the guardianship laws that once restricted Saudi women’s autonomy.

Through her art, the artist captures the complexities of a society in flux, reflecting a newfound visibility for women in the public sphere and a reshaping of traditional gender roles. Her work exemplifies the spirit of a Saudi renaissance, where artistic expression serves as a powerful tool for both personal and collective commentary on the changing fabric of Saudi society.[150]

Similarly, in her 2022 work Just Paper, the artist presents delicate porcelain scrolls with smooth, slightly glossy surfaces, onto which she imprints Arabic script. Using silkscreen printing, she transfers text from now-decommissioned religious books before rolling the porcelain. This artwork symbolizes the historical perception of women as fragile, requiring protection – much like the porcelain itself, which risks breaking if handled or read too closely. Through this piece, Al Dowayan challenges the authority of religious texts written by men, reclaiming the power of words. Additionally, the work evokes the women-only spaces from her past, spaces free from the control of the former religious police.[151]

Conclusion

The evolution of the art scene in Saudi Arabia and the role that women played throughout the years was heavily influenced by the shifts and changes that occurred within the Kingdom’s social and educational landscape. Each era saw varying developments related to broader cultural, political, and economic transformations that affected access to education and art and has been deeply intertwined with the nation's journey from its inception as a modern state to its current position on the global stage. Educational institutions, which initially focused on more conventional and conservative subjects, have increasingly opened their doors to art programs that embrace both local traditions and global trends. This shift has been crucial in fostering the growth of a contemporary art scene, one in which women have begun to play a prominent role.

The changes introduced by Vision 2030 have opened doors for artists to explore themes of identity, social change, and empowerment. The impact of these changes on women's participation in visual art has been significant, especially in relation to access to the tools, platforms, and networks necessary to pursue careers in the arts. Despite facing a myriad of societal and cultural challenges, women artists in Saudi Arabia have steadily built recognition both locally and internationally. Their increasing visibility within the art world reflects the broader societal shifts towards greater gender equality and empowerment.

Bibliography

"Abdel Halim Radwi." Jameel National Gallery of Fine Arts. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://nationalgallery.org/artist/abdel-halim-radwi.

"Al-Qatt al-Asiri: Female Traditional Interior Wall Decoration in Asir, Saudi Arabia." UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Accessed January 24, 2025. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/al-qatt-al-asiri-female-traditional-interior-wall-decoration-in-asir-saudi-arabia-01261.

"Beyond Tradition and Modernity: Dilemmas of Transformation in Saudi Arabia." Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, May 14, 2018. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://studies.aljazeera.net/en/reports/2018/05/tradition-modernity-dilemmas-transformation-saudi-arabia-180514084243670.html.

"King Fahd Cultural Center." Saudipedia. Accessed December 3, 2024. https://saudipedia.com/en/article/1996/culture/cultural-affairs/king-fahd-cultural-center.

"Saudi Arabia and Political, Economic, and Social Development." Vision 2030 Report. May 2017. Accessed November 13, 2024.

"Saudi Vision 2030: A Blueprint for Transformative Change." Saudi Arabia Insights, August 7, 2024. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://saudiarabia.com/insights/saudi-vision-2030-a-blueprint-for-transformative-change/.

"The Saudi Artists Who Paved the Way." Ithra. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.ithra.com/en/news/saudi-artists-who-paved-way.

Afary, Janet. "Iranian Revolution: Summary, Causes, Effects, & Facts." Encyclopaedia Britannica, last updated October 26, 2024. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Iranian-Revolution.

Alajmi, Nouf. “Overcoming Obstacles: Portrayal of Saudi Women through Art.” Riyadh: Scientific Research Publishing, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4236/adr.2019.72006.

Al Jazeera. "The Sixties in the Arab World: Culture." Al Jazeera World, August 11, 2022. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/program/al-jazeera-world/2022/8/11/the-sixties-in-the-arab-world-culture.

Albakri, Ghadah Shukri H. Transforming Art Education in Saudi Arabia: Inclusion of Social Issues in Art Education. PhD diss., University of North Texas, 2020. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1707324/m2/1/high_res_d/ALBAKRI-DISSERTATION-2020.pdf.

Alharbi, Fahad. "The development of curriculum for girls in Saudi Arabia." Creative Education 5, no. 24 (2014): 2021.

Al-Harbi, Yousif. "The Renaissance of Saudi Art." Ithraeyat, August 13, 2023. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://ithraeyat.ithra.com/ar/editions.

Al-Jamil, Fawz. The Story of the Beginnings: The Role of Saudi Institutions in the Growth of Art Education. Translated by the platform. December 2, 2024. Mana. https://en.mana.net/the-story-of-the-beginnings-the-role-of-saudi-institutions-in-the-growth-of-art-education/.

Al-Rasheed, Madawi. A History of Saudi Arabia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Al-Rasheed, Madawi. A Most Masculine State: Gender, Politics, and Religion in Saudi Arabia. London: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Al-Senan, Maha. "Considerations on Society Through Saudi Women's Art." International Journal of Development Research 5, no. 5 (2015): 4536.

Amos, Deborah. "A New Generation of Saudi Artists Pushes the Boundaries." KQED, February 8, 2016. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.kqed.org/arts/11310418/a-new-generation-of-saudi-artists-pushes-the-boundaries.

Austin, Peter E. "Middle East – Saudi Arabia." The 1960s Project. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.the1960sproject.com.

Ayad, Myrna. "So Much to Say, So Much to See and So Much Has Happened: Khamseen – 50 Years of Saudi Art." Sotheby’s Modern & Contemporary Middle East, August 8, 2024. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/so-much-to-say-so-much-to-see-and-so-much-has-happened-khamseen-50-years-of-saudi-art.

Choudhary, Homara. “The Rise of Contemporary Art in the Arabian Gulf.” AramcoWorld, July 1, 2024. https://www.aramcoworld.com/articles/2024/the-rise-of-contemporary-art-in-the-arabian-gulf

Foley, Sean. Changing Saudi Arabia: Art, Culture, and Society in the Kingdom. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2019.

Hamdan, Amani. "Women and education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and achievements." International Education Journal 6, no. 1 (2005): 42-64.

Khadraoui, Wided Rihana. "Don’t Forget the Women Who Forged Saudi Arabia’s Art Scene." Artsy, July 13, 2018. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-forget-women-forged-saudi-arabias-art-scene.

Lieske, Diana Elena. "Saudi Contemporary Art as a commentary on the social issues present in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the 21st century." (2017).

Lutfi, Dina Abdelhamid. Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education in Saudi Arabia Within High Schools and Colleges. EdD diss., Teachers College, Columbia University, 2018. https://lib.manaraa.com/books/Understanding%20the%20Dynamics%20of%20Art%20Education%20in%20Saudi%20Arabia%20within%20High%20Schools%20and%20Colleges.pdf.

Mater, Ahmed. "Development of the Saudi Art Scene from 1960." Ahmed Mater Official Website. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.ahmedmater.com/essays/development-of-the-saudi-art-scene-from-1960.

Shamra, Gouri. “Manal AlDowayan on Keeping Pace with Change.” Frieze, April 18, 2024. https://www.frieze.com/article/venice-biennale-2024-manal-aldowayan-profile.

Solomon, Tessa. "Safeya Binzagr, Pioneering Artist Who Preserved Saudi Arabia’s Culture, Dies at 84." ARTnews, September 13, 2024. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/safeya-binzagr-artist-dead-1234717569/.

[1] Maha Al-Senan, "Considerations on Society Through Saudi Women's Art," International Journal of Development Research 5, no. 5 (2015), 4536.

[2] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society,” 4536.

[3] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society,” 4536.

[4] Qaryat Al Faw was the capital of the first Kindah kingdom. It is located about 700 km southwest of Riyadh, the capital city of Saudi Arabia.

[5] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society,” 4536.

[6] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society,” 4536.

[7] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society,” 4536.

[8] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society,” 4536.

[9] UNESCO, “Al-Qatt Al-Asiri, female traditional interior wall decoration in Asir, Saudi Arabia,” 2017, accessed January 2025, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/al-qatt-al-asiri-female-traditional-interior-wall-decoration-in-asir-saudi-arabia-01261

[10] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society,” 4536.

[11] Ahmed Mater, “Development of the Saudi Art Scene from 1960,” https://www.ahmedmater.com/essays/development-of-the-saudi-art-scene-from-1960

[12] Fouad C. Khalifeh, “Saudi Vision 2030: A Blueprint for Transformative Change,” August 7, 2024, https://saudiarabia.com/insights/saudi-vision-2030-a-blueprint-for-transformative-change/

[13] Muhammad Bin Saud Al Muqrin Al Saud; (1687–1765), also known as Ibn Saud, was the emir of Diriyah and is considered the founder of the First Saudi State and the Saud dynasty, named after his father, Saud bin Muhammad Al Muqrin.His reign lasted between 1727 and 1765.

[14] Abdulaziz Bin Muhammad Al Saud (1720–1803) was the second ruler of the Emirate of Diriyah. He was the eldest son of Muhammad bin Saud and the son-in-law of Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab. Abdulaziz ruled the Emirate from 1765 until 1803.

[15] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society Through Saudi Women’s Art,” 4536.

[16] Peter E. Austin, “Middle East – Saudi Arabia,” The 1960s Project, accessed November 13, 2024, https://www.the1960sproject.com.

[17] Austin, “Middle East – Saudi Arabia.”

[18] Fahad Alharbi, “The Development of Curriculum for Girls in Saudi Arabia,” Creative Education 5, no. 24 (2014): 2021, https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2014.524229

[19] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society,” 4536

[20] Austin, “Middle East - Saudi Arabia.”

[21] Austin, “Middle East – Saudi Arabia.”

[22] Ghadah Shukri H. Albakri, Transforming Art Education in Saudi Arabia: Inclusion of Social Issues in Art Education, (PhD diss., University of North Texas, 2020), 15-16.

[23] Albakri, Transforming Art Education, 15.

[24] Albakri, Transforming Art Education, 15.

[25] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society,” 4536.

[26] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society,” 4537.

[27] Al-Senan, “Considerations on Society,” 4537.

[28] The Saudi Arabian throne succession follows a lineage within the House of Saud. After each King's death, the crown prince typically succeeds him, chosen through a loose system of seniority among the sons of Ibn Saud. However, various family members have been passed over for different reasons over time. King Saud was King Ibn Saud’s second son.

[29] Dina Abdelhamid Lutfi, Understanding The Dynamics of Art Education in Saudi Arabia Within Highschool and Colleges, (PhD. diss, Columbia University, 2018), 202.

[30] Albakri, Transforming Art Education, 15.

[31] Albakri, Transforming Art Education, 16

[32] Albakri, Transforming Art Education, 16.

[33] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 86.

[34] Austin, “Middle East – Saudi Arabia.”

[35] Austin, “Middle East – Saudi Arabia.”

[36] Austin, “Middle East – Saudi Arabia.”

[37] Second son of Abdulaziz Al Saud (Ibn Saud)

[38] After King Saud ascended to the throne in 1953, King Faisal was appointed Crown Prince and served as foreign minister. In 1958, amid an economic downturn, King Saud delegated full executive authority to him. King Faisal briefly resigned in 1960 but resumed his roles in 1962. By March 1964, he assumed complete executive control. King Saud was removed from power by religious leaders, senior members of the ruling family, and the Council of Ministers. Subsequently, King Faisal was crowned king in November 1964.

[39] Madawi Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 116-123.

[40] Sean Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia: Art, Culture, and Society in the Kingdom (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2019).

[41] Austin, “Middle East – Saudi Arabia.”

[42] Mater, “Development of the Saudi Art Scene from 1960”

[43] Abdel Halim Radwi, National Gallery, accessed January 29, 2025, https://nationalgallery.org/artist/abdel-halim-radwi/

[44] Myrna Ayad, “So Much to Say, So Much to See and So Much Has Happened – Khamseen: 50 Years of Saudi Art,” August 8, 2024, https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/so-much-to-say-so-much-to-see-and-so-much-has-happened-khamseen-50-years-of-saudi-art

[45] Austin, “Middle East – Saudi Arabia.”

[46] Alharabi, “The Development of Curriculum,” 2.

[47] Alharabi, “The Development of Curriculum,” 2-3.

[48] Fawz Al-Jamil, The Story of the Beginnings: The Role of Saudi Institutions in the Growth of Art Education, trans. by Mana Platform, December 2, 2024, Mana, https://en.mana.net/the-story-of-the-beginnings-the-role-of-saudi-institutions-in-the-growth-of-art-education/.

[49] Albakri, Transforming Art Education, 18.

[50] Tessa Solomon, "Safeya Binzagr, Pioneering Artist Who Preserved Saudi Arabia’s Culture, Dies at 84," ARTnews, September 13, 2024, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/safeya-binzagr-artist-dead-1234717569/.

[51] Solomon, “Safeya Binzagr”.

[52] Al-Jamil, The Story of the Beginnings.

[53] Al-Jamil, The Story of the Beginnings.

[54] Alharbi, “The Development of Curriculum,” 3.

[55] Albakri, Transforming Art Education, 18.

[56] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 89.

[57] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 89.

[58] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 89.

[59] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 89.

[60] Mater, “Development of the Saudi Art Scene from 1960”

[61] Mater, “Development of the Saudi Art Scene from 1960”

[62] Austin, “Middle East – Saudi Arabia.”

[63] King Abdulaziz bin Rahman’s (Ibn Saud) fifth son.

[64] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 176.

[65] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 88, citing Ministry of Education, 2005, p. 21.

[66] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 88.

[67] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 138.

[68] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 130.

[69] On November 20, 1979, a group of Islamic extremists, led by Saudi preacher Juhayman al-Otaybi, attacked the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca. The assailants, including militants from various regions of the Muslim world and some American converts, took control of the mosque, trapping tens of thousands of worshippers inside. The siege lasted two weeks and resulted in hundreds of casualties. The situation was eventually resolved through the intervention of the Saudi National Guard and French Special Forces.

[70] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 130-157.

[71] King Ibn Saud’s eighth son.

[72] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 130-157.

[73] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 130-157.

[74] Nouf Alajmi, “Overcoming Obstacles: Portrayal of Saudi Women through Art,” (Riyadh: Scientific Research Publishing, 2019), https://doi.org/10.4236/adr.2019.72006.

[75] Al-Jamil, The Story of the Beginnings.

[76] Al-Jamil, The Story of the Beginnings.

[77] Al-Jamil, The Story of the Beginnings.

[78] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 146.

[79] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 130-157.

[80] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 130-157.

[81] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 130-157.

[82] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 150.

[83] The Islamic Revolution in Iran was a major political and social upheaval that overthrew the Pahlavi monarchy, replacing it with an Islamic theocracy under Ayatollah Khomeini. It inspired movements across the region to reassert Islamic governance and values.

[84] Janet Afary, "Iranian Revolution: Summary, Causes, Effects, & Facts." Last updated October 26, 2024. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Iranian-Revolution.

[85] Aseel Bashraheel, “Rise and fall of the Saudi religious police,” September 22, 2019, https://www.arabnews.com/node/1558176/saudi-arabia

[86] Madawi Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State: Gender, Politics, and Religion in Saudi Arabia, (London: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 20.

[87] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 20.

[88] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 25.

[89] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 114.

[90] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 114.

[91] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 124-125.

[92] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 39.

[93] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 20.

[94] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 108-133.

[95] Deborah Amos, “A New Generation of Saudi Artists Pushes the Boundaries,” February 9,2016, https://www.kqed.org/arts/11310418/a-new-generation-of-saudi-artists-pushes-the-boundaries

[96] King Fahd Cultural Center, Saudipedia, accessed Februrary 2, 2025, https://saudipedia.com/en/article/1996/culture/cultural-affairs/king-fahd-cultural-center

[97] Mignanego, ““Saudi Arabia: Soft Power through Contemporary Art,” https://www.luxurytribune.com/en/saudi-arabia-soft-power-through-contemporary-art

[98] Wided Rihana Khadraoui, “Don’t Forget the Women Who Forged Saudi Arabia’s Art Scene,” July 13, 2018, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-forget-women-forged-saudi-arabias-art-scene

[99] Bashraheel, “Rise and fall of the Saudi religious police,” https://www.arabnews.com/node/1558176/saudi-arabia

[100] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 134-174.

[101] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 134-174.

[102] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 134-174.

[103] Amani Hamdan, "Women and Education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and Achievements," International Education Journal 6, no. 1 (2005): 44.

[104] Hamdan, “Women and Education,” 44. The incident, in which religious police allegedly prevented firemen from rescuing the girls due to concerns over modesty, sparked public outrage and led to debates over the role of the religious police and the state of women's education in Saudi Arabia. Prior to the fire, public dissatisfaction had already grown due to the inadequate funding and unsafe conditions of girls' schools.

[105] Hamdan, “Women and Education,” 44.

[106] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 134-174.

[107] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 161.

[108] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 134-174.

[109] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 134-174.

[110] King Ibn Saud’s eleventh son.

[111] King Ibn Saud’s twenty-fifth son.

[112] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 260.

[113] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 269-270.

[114] Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia, 270.

[115] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 21.

[116] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 138.

[117] Al-Rasheed, A Most Masculine State, 134-174.

[118] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 180-181.

[119] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 7-9.

[120] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 11.

[121] Lutfi, Understanding the Dynamics of Art Education, 11.

[122] Wided Rihana Khadraoui, "Don’t Forget the Women Who Forged Saudi Arabia’s Art Scene," Artsy, July 13, 2018, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-forget-women-forged-saudi-arabias-art-scene.

[123] Khadraoui, "Don’t Forget the Women."

[124] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 38.

[125] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 43.

[126] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 47.

[127] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 44.

[128] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 50.

[129] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 50-51.

[130] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 46-54.

[131] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 51-52.

[132] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 46-54.

[133] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 163-188.

[134] https://www.ahmedmater.com/biography

[135] https://miskartinstitute.org/en/about

[136] Princess Nourah Bint Abdul Rahman University, https://pnu.edu.sa/ar/Pages/Home.aspx

[137] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 163-188.

[138] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 163-188.

[139] Foley, Changing Saudi Arabia, 163-188.

[140] Diana Elena Lieske, Saudi Contemporary Art as a Commentary on the Social Issues Present in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the 21st Century (2017).

[141] Desert X, https://desertx.org/

[142] Misk Art Week, https://miskartinstitute.org/en

[143] Khalideh, “Saudi Vision 2030: A Blueprint for Transformative Change.”

[144] Bashraheel, “Rise and fall of the Saudi religious police,” https://www.arabnews.com/node/1558176/saudi-arabia

[145] Princess Nourah Bint Abdul Rahman University, https://pnu.edu.sa/ar/Pages/Home.aspx

[146] King Abdulaziz University, https://www.kau.edu.sa/home_english.aspx

[147] Ithra by Aramco, https://www.ithra.com

[148] Diriyah Biennale Foundation, https://biennale.org.sa

[149] Gouri Shamra, “Manal AlDowayan on Keeping Pace with Change,” Frieze, April 18, 2024, https://www.frieze.com/article/venice-biennale-2024-manal-aldowayan-profile

[150] Homara Choudhary, “The Rise of Contemporary Art in the Arabian Gulf,” AramcoWorld, July 1, 2024,https://www.aramcoworld.com/articles/2024/the-rise-of-contemporary-art-in-the-arabian-gulf

[151] Christelle Al Chamy, “Manal Al Dowayan: Biography”, Accessed February 7, 2025. https://dafbeirut.org/en/MANAL-AL-DOWAYAN.

Comments on A Cultural Landscape in Flux: The Evolution of Saudi Art and Society