18th and 19th Century Printmaking: Planography/Lithography, Offset, and Silkscreen – (Germany, England, and France)

It was not until over a century later, in 1796 CE, that a radical new print process was developed when Alois Senefelder, a German actor and playwright who wanted to print his own plays, developed lithography, a chemical printing process on limestone. To produce a lithograph, an image is drawn on a flat surface, most commonly made of limestone, and at times metal, with a greasy material, such as crayons or oily ink. The surface is dampened with water, which repels the greasy design, while ink adheres only to the greasy areas. When pressed onto paper using a flatbed lithographic press, the ink transfers the image preserving the artist's original marks, enabling a variety of effects resembling pen lines, crayon drawings, or brushwork.

Lithography was the first printmaking process, also known as planography, where image and background areas were on the same level. This allowed printmakers to create a wider range of tone and markings, and reduced the need for years of training and precise skill needed for woodblock carving, metal engraving, or mezzotint burnishing, making printmaking more accessible to artists.

.jpeg)

At the end of the 19th century CE, mechanical developments further industrialized printmaking and hugely increased the speed and quantity of prints. In England, 1875 CE, Robert Barclay developed rotary offset printing, which used the chemical process of lithography on a rotating cylinder to transfer an image from a metal plate to a rubber blanket and then to the printing surface. Just five years later, the British Arts and Crafts movement sought to move away from mass production and mechanization, calling for a return to craft techniques made by hand, which fueled an interest in woodcuts and printmaking as a crucial art form moving into the 20th century CE.[1]

Silkscreen-printing was introduced to Europe via the Silk Road[2] trade in the 18th century CE, but did not gain traction until the 19th century CE when silk became an affordable resource in Europe. English and French craftsmen began to use screens of silk and stencils for printing on fabric and copying the Japanese fabrics in world fairs. In 1907 CE, Englishman Samuel Simon patented the process.

Early in 1910 CE, along with photography, screen printers began experimenting with photo-reactive chemical processes, whereby a photosensitive emulsion is applied evenly to the screen and a transparent film with the desired design is placed on top. When exposed to light, the emulsion hardens the areas not covered by the design, creating a stencil through which ink can pass. This photo-emulsion method replaced the earlier manual process of cutting stencils by hand, offering greater detail and efficiency in screen-printing.

20th Century Printmaking

Art printmaking experienced a global artistic revival in the 20th century as an avant-garde and revolutionary art medium. Reproducible and accessible, the print genre was both an artistic pushback to mechanization and a way for artists' work to be more politically engaged. Artists set out to explore traditional, non-commercial methods in creating prints that could be appreciated as unique works of art.

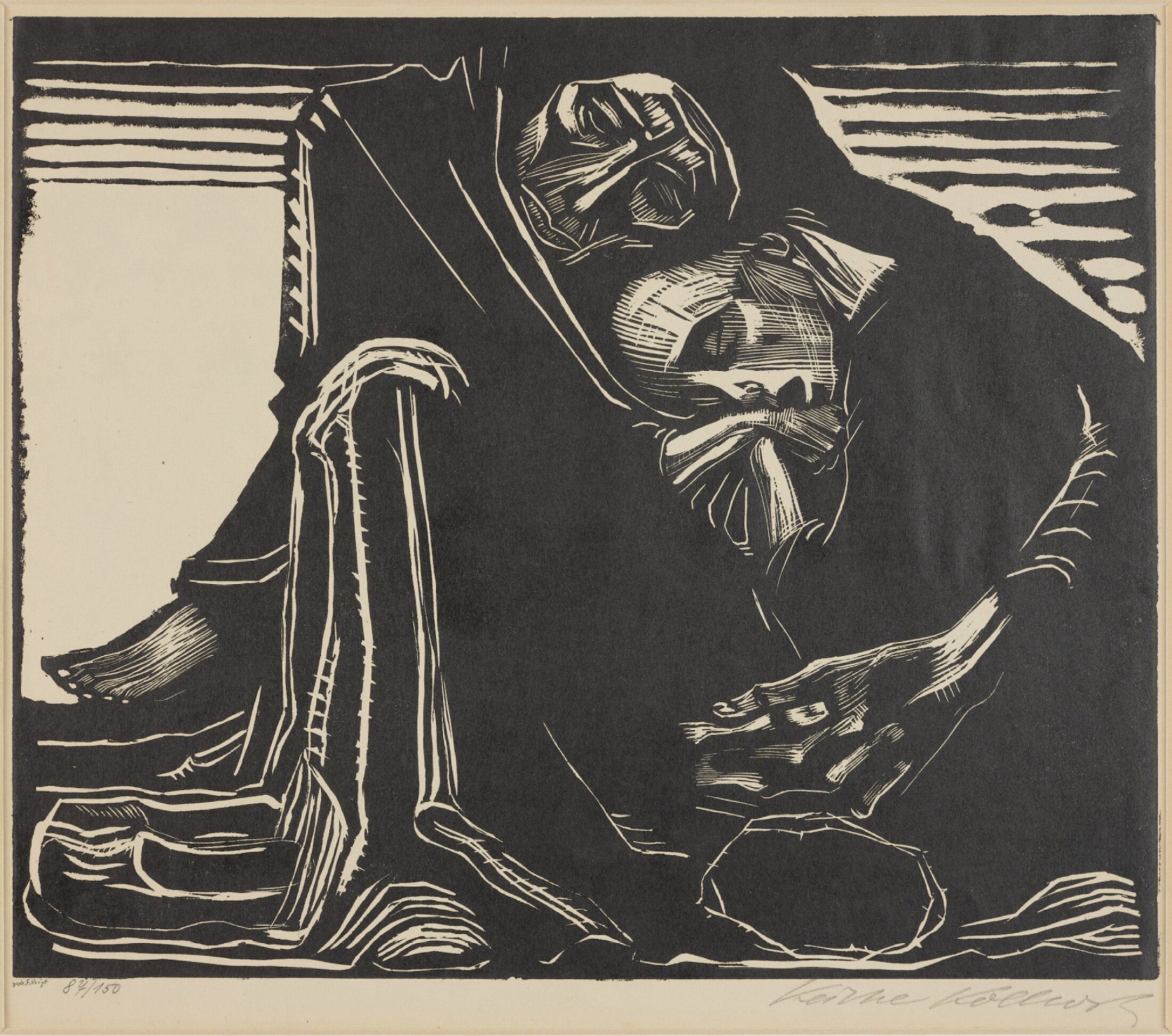

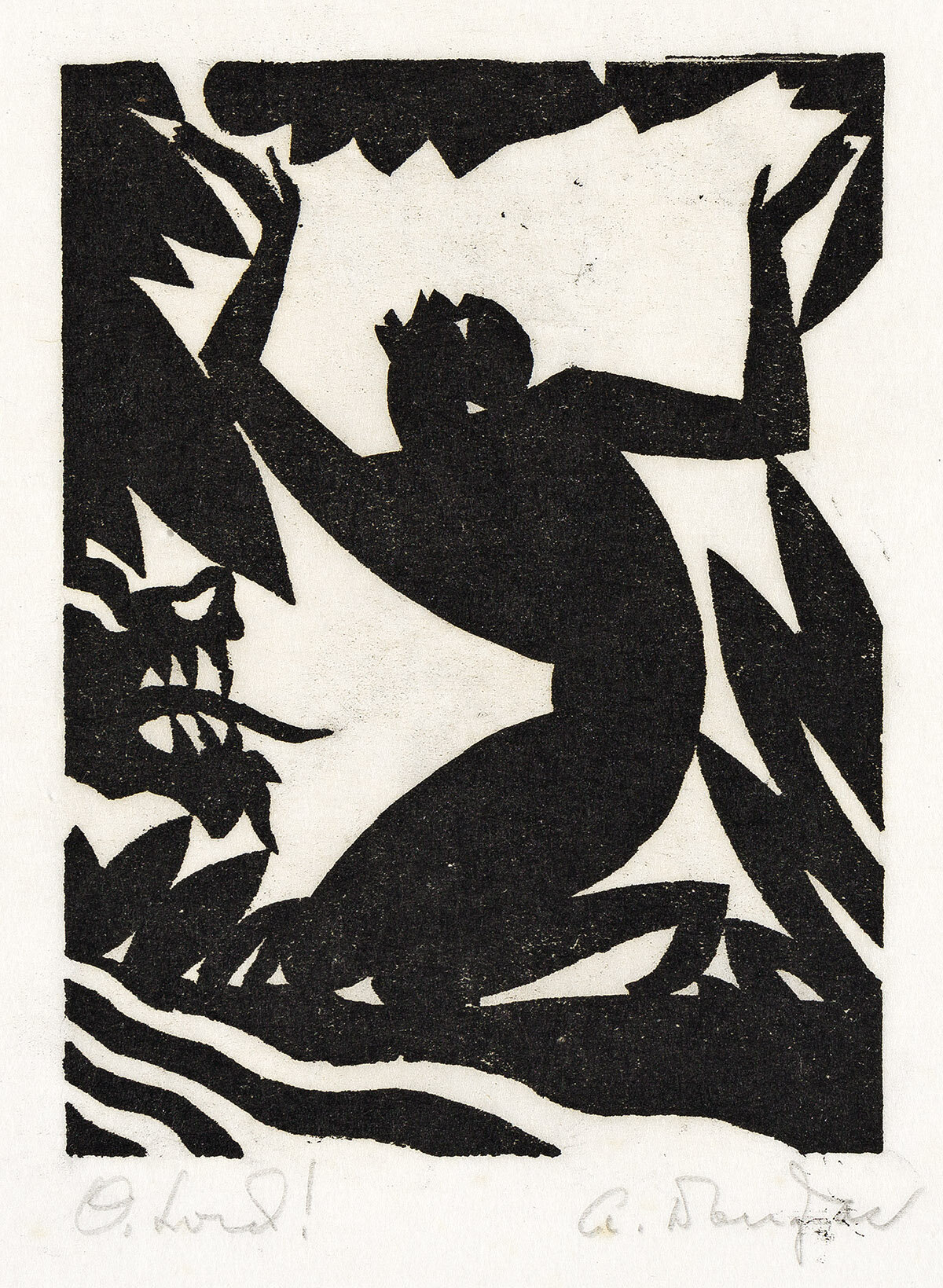

Many avant-garde European artists and movements explored and experimented with printmaking. German art movements from the turn of the century until the Second World War[3][4] gave special importance to woodcut, lithography, and etching often to depict the horrors of war in expressionist simplicity.

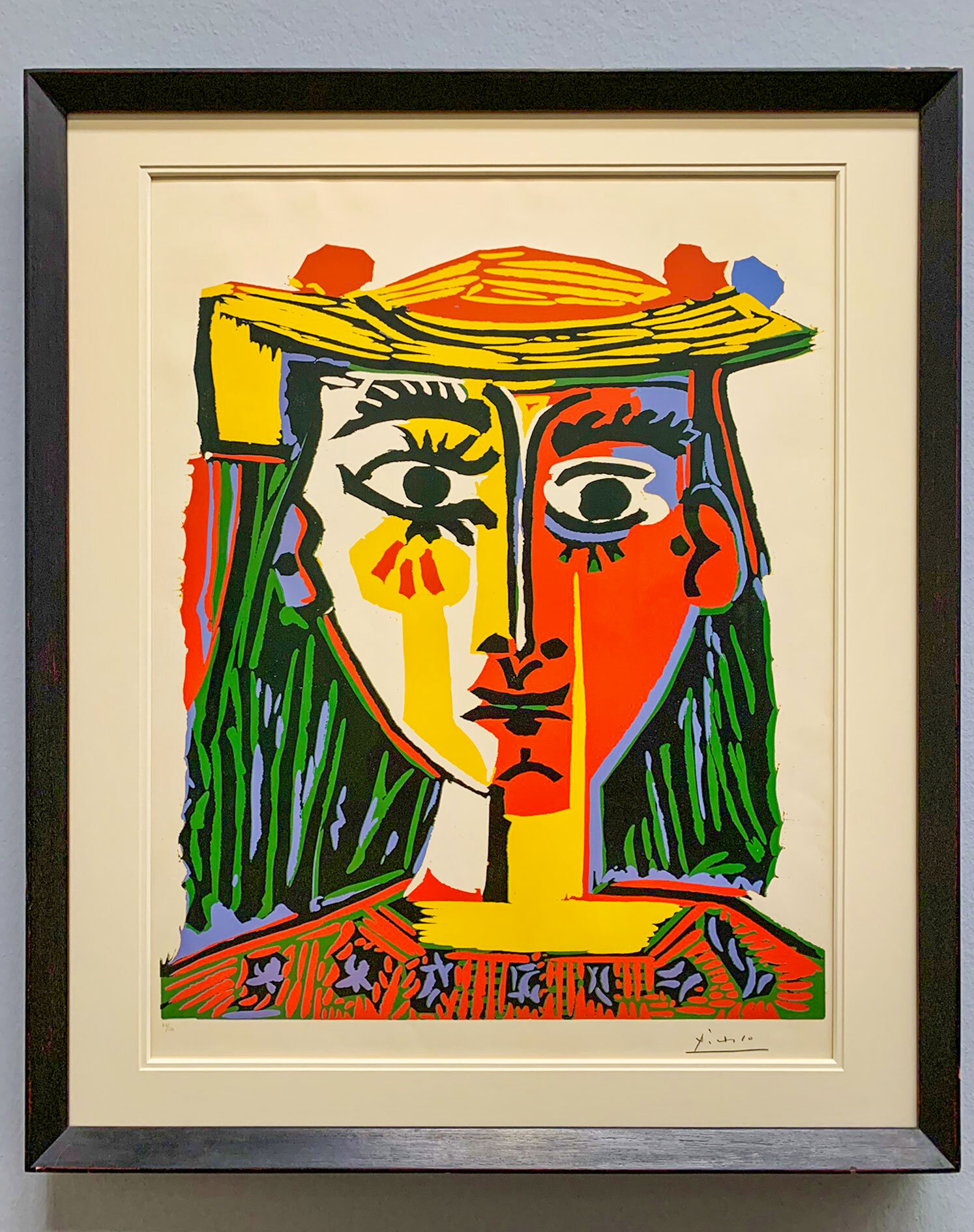

French artist Jean Dubuffet rebelled against high fine art by working in print as a popular medium, where he would radically experiment with techniques, attacking lithography stones with sandpaper, chemicals, and flaming rags.[5] Despite never being formally trained, Spanish artist Pablo Picasso was a prolific printmaker, producing over 2,000 prints in lithography, etching, drypoint, and woodcut throughout his life.[6] His work solidified printmaking as a thoroughly modern fine art medium.

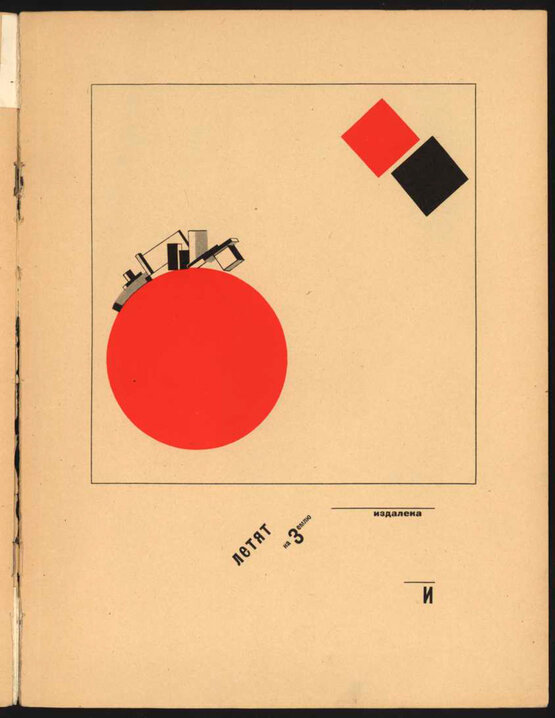

Globally, politically conscious artists of the 20th century also found refuge in printmaking as an accessible art of the people. Russian avant-garde artists such as El Lissitsky taught printmaking to emerging artists as a revolutionary and working-class art form.[7] Though better known for their mural work, Mexican post-revolutionary artists such as Diego Rivera were equally engaged in printmaking, with both murals and prints accessible to the public.[8][9]

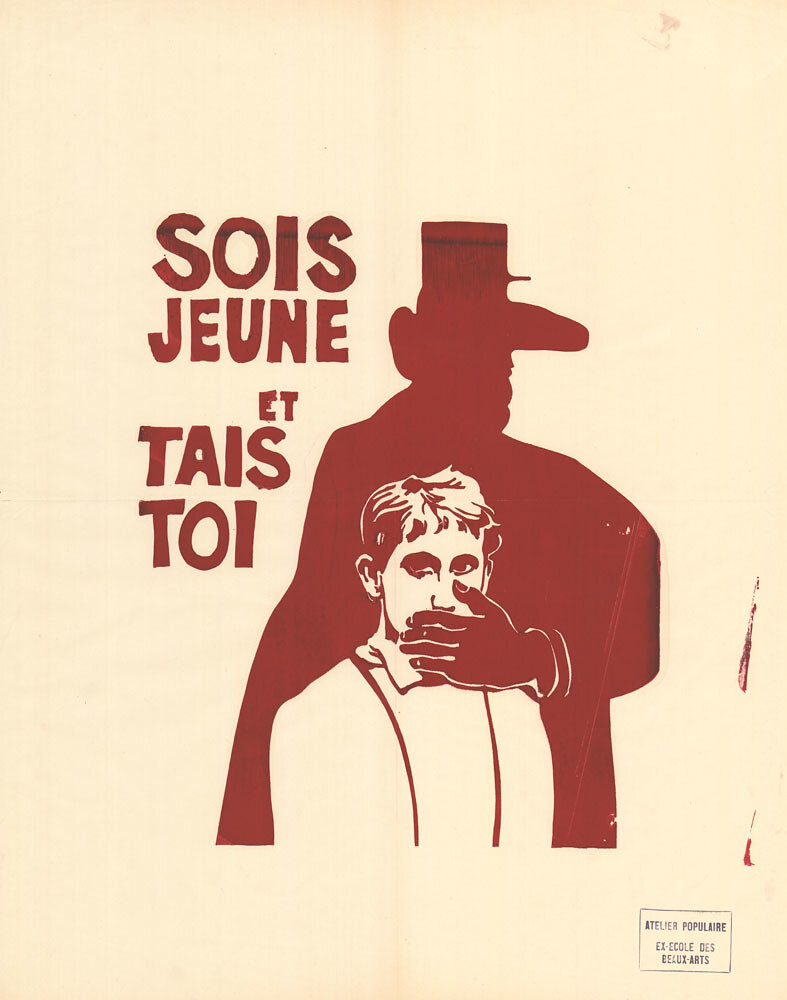

Social realist artists such as Max Beckman, also favored printmaking for its simplicity to depict daily lives, and its accessibility to working people.[10] Significantly, during the May '68 student protests[11] the Atelier Populaire was formed at the Paris School of Fine Arts. This group of art students created anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist silkscreen print posters transforming the city into an open-air exhibition.[12]

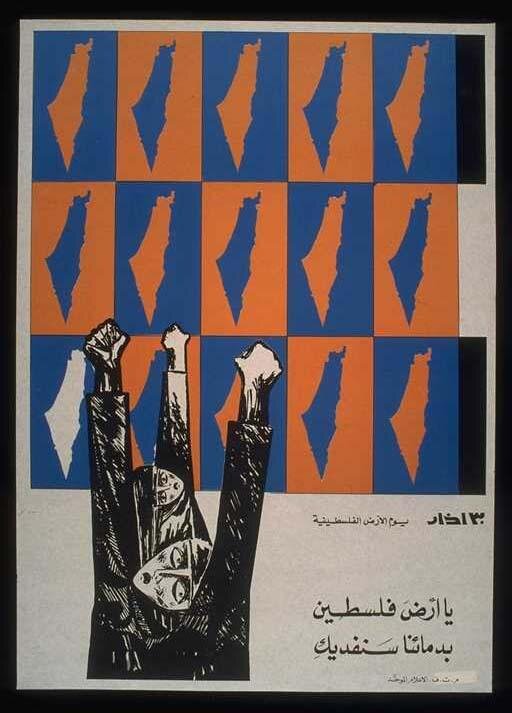

The proliferation of artist prints as posters for a political cause would have a huge impact in spreading printmaking expertise and influence globally through anti-imperialist networks. In this context, artist printmaking culture on the streets materialized new aesthetic modes of transnational resistance,[13] and connected art and political movements from Cuba, Algeria, Palestine, and Vietnam.[14]

Throughout the century, artists used printmaking to critique Western cultural and political norms. In New York, establishing a modern Afrocentric avant-garde in the visual arts against a largely white art scene, the Harlem Renaissance (1918-1935) used printmaking, particularly woodcuts, to combine African and European influences. The later Black Art Movement would utilize silkscreen posters influenced by the Harlem Renaissance as their primary medium for artistic innovation and visual communication.[15]

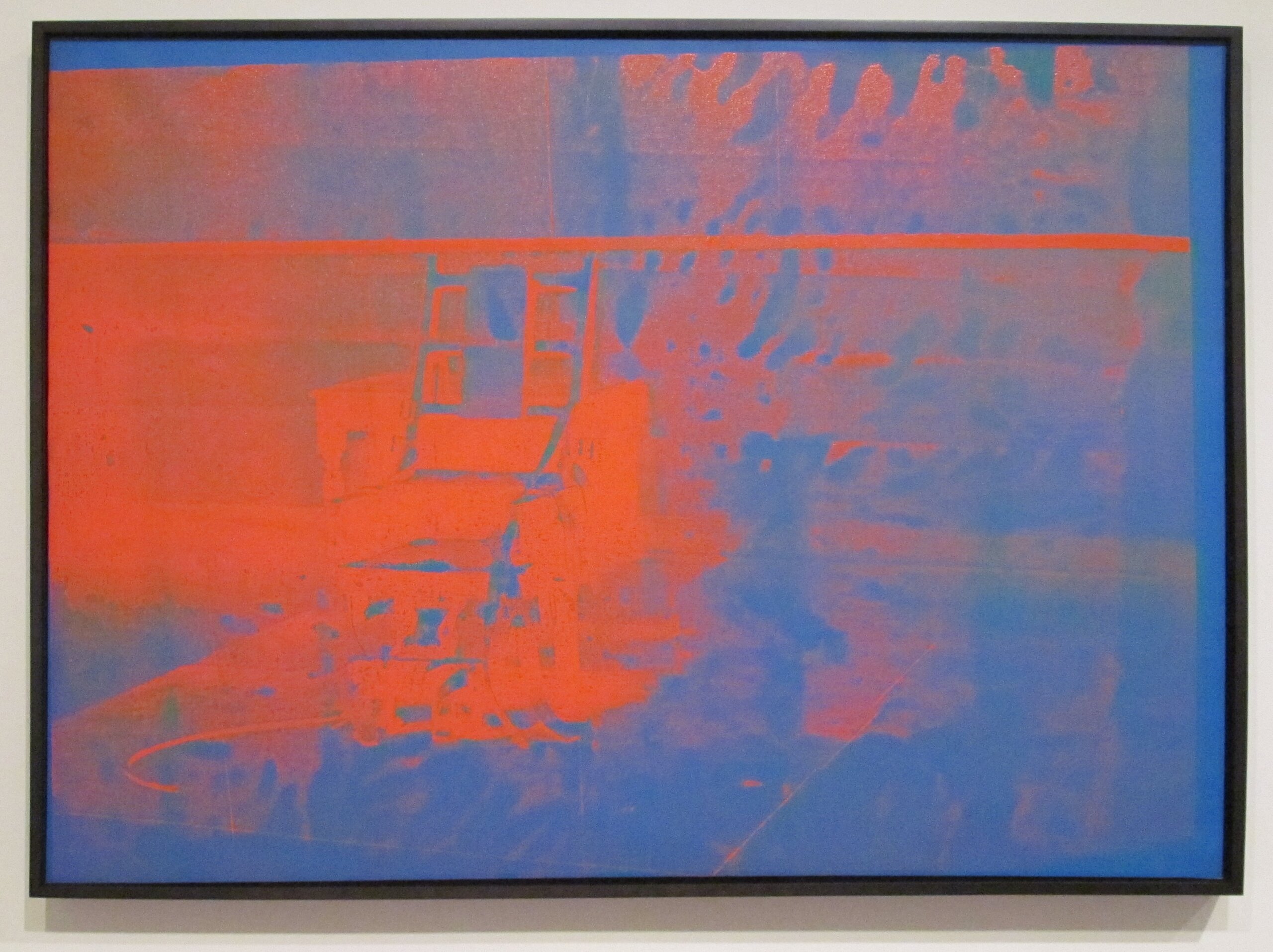

In the 1960s, Pop art emerged in the United States as a garish critique of mass media and a mechanized, detached society driven by consumption. Andy Warhol used silkscreen, a stencil printing technique through a fine mesh, which was then a medium dominated by advertising, to proliferate his message and art. The group of New York feminist artists, The Guerrilla Girls, also used silkscreen to address the underrepresentation of women in art.[16]

Throughout the century, printmakers across the globe combined and experimented with the chemical and physical possibilities of integrating different elements of the various traditional printmaking techniques, pushing the boundaries of the medium and often reflecting the political upheavals and causes of their time. Printmaking was at the forefront of both avant-garde and revolutionary art as well as artistic experimentation, where the new challenges and global issues of their time called for direct physical engagement with tools and materials.

Conclusion

The history of printmaking attests to the relentless creative and technological experimentation of humans throughout history. Although printmaking is accessible and widespread, printmaking as a medium has never been simply about reproduction. Throughout time, the medium of printmaking has facilitated radical artistic innovation, leading to the creation of unexpected new forms. From its ancient origins in Mesopotamia with stamp and cylinder seal printing, through the forgotten chapter of medieval tarsh printing, to the highly specialized and experimental printmakers of the 20th century, printmaking has evolved through various physical and chemical innovations, shaping the dissemination of image and text across cultures and continents.

Bibliography

“A Short History of the Poster.” Victoria and Albert Museum. Accessed August 31, 2024. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/a-short-history-of-the-poster?srsltid=AfmBOopl2Miq37LgSOF-vVrAHyOItiJQyiHTZ165s_4F82PVlPG_zFkg.

Abrams, Harry. Impressions of the 20th Century: Fine Art Prints from the V&A Collection. Victoria and Albert Museum, 2001.

Carter, Thomas Francis. The Invention of Printing in China and its Spread Westward. Columbia University Press, 1925.

Christensen, Thomas. “Guttenberg and the Koreans.” In River of Ink: An Illustrated History of Literacy. Counterpoint, 2014.

“Diamond Sutra Frontispiece.” Dunhuang. Accessed May 31, 2024. http://idp.bl.uk/collection/9C9BE31B79574FC88CEC5569171D8177/?return=%2Fcollection%2F%3Fterm%3Ddiamond%2Bsutra.

Finlay, Nancy. “American Printmaking in the Twentieth Century.” The Princeton University Library Chronicle 42, no. 2 (1981): 104–12. https://doi.org/10.2307/26402233.

Freeman, Nigel. “The Art of the Harlem Renaissance, in Print and Plaster.” Swann Galleries. March 25, 2024. https://www.swanngalleries.com/news/african-american-art/2024/03/the-art-of-the-harlem-renaissance-in-print-and-plaster/.

German Expressionist Prints. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1995.

Hnaihen, Kadim Hasson. "The appearance of bricks in ancient mesopotamia." Athens Journal of History 6, no. 1 (2020): 73-96.

Hoe, Robert. A Short History of the Printing Press. Good Press, 2021.

Maasri, Zeina. Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut's Global Sixties. Vol. 13. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

MacPhee, Josh, ed. Paper politics: Socially engaged printmaking today. PM Press, 2009.

McDonald, Mark. “Printmaking in Mexico, 1900–1950.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. September 2016. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/prmx/hd_prmx.htm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Cylinder Seal and Modern Impression. Accessed August 31, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/329090.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Stamp Seals of the Hittite Old Kingdom. Accessed August 31, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/327799.

Mayer, Ralph. The HarperCollins Dictionary of Art Terms and Techniques. 2nd ed. New York: HarperCollins, 1991.

Oregon State Library. “Gutenburg Press.” Special Collections & Archives McDonald Collection. Accessed May 31, 2024. https://scarc.library.oregonstate.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/mcdonald/incunabula/gutenberg/.

The Museum of Modern Art. “German Expressionism Techniques.” Accessed May 31, 2024. https://www.moma.org/s/ge/curated_ge/techniques/index.html.

The Museum of Modern Art. “Three Masters of the Bauhaus: Lyonel Feininger, Vasily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee.” Accessed May 31, 2024. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/417.

Roper, Geoffrey. ‘Arabic Printing Culture’. Encyclopedia of Mediterranean Humanism, 2014. https://encyclopedie-humanisme.com/?Arabic-printing.

Samudzi, Zoé. “Dindga McCannon and the Fabric of the Black Arts Movement.” BlackStar Film Festival, Issue 004, Summer 2022. https://www.blackstarfest.org/seen/read/issue004/dindga-mccannon-zoe-samudzi/.

Sanders, Phil. Prints and Their Makers. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2020.

Seri, Andrea. "Adaptation of cuneiform to write Akkadian." Visible language. inventions of writing in the Ancient Middle East and beyond 32 (2010): 85-98.

Shatzmiller, Maya. "The adoption of paper in the Middle East, 700-1300 AD." Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 61, no. 3 (2018): 461-492.

“Social Realism Prints, Works on Paper and Multiples.” Printed Editions. Accessed May 31, 2024. https://www.printed-editions.com/art-movement/social-realism/.

Stijnman, Ad. Engraving and etching 1400-2000: a history of the development of manual Intaglio printmaking processes. Archetype Publ., 2012.

Suzuki, Sarah. “Jean Dubuffet.” The Museum of Modern Art. Accessed May 31, 2024. https://www.moma.org/artists/1633.

"The Invention of Woodblock Printing in the Tang and Song Dynasties." Asian Art Museum. Accessed August 31, 2024. https://education.asianart.org/resources/the-invention-of-woodblock-printing-in-the-tang-and-song-dynasties/.

Thompson, Wendy. “The Printed Image in the West: History and Techniques.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2003. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/prnt/hd_prnt.htm.

Tikannen, Amy. “Offset Printing.” Britannica. Accessed May 31, 2024.

Topçuoğlu, Oya. Iconography of Protoliterate Seals. na, 2010.

[1] Josh MacPhee, ed., Paper Politics: Socially Engaged Printmaking Today (Oakland: PM Press, 2009); Amy Tikannen, “Offset Printing,” Britannica, accessed May 31, 2024.

[2] The Silk Road network is generally thought of as stretching from an eastern terminus at the ancient Chinese capital city of Chang’an (now Xi’an) to westward end-points at Byzantium (Constantinople), Antioch, Damascus, and other Middle Eastern cities.

[3] The Museum of Modern Art, “Three Masters of the Bauhaus: Lyonel Feininger, Vasily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee,” accessed May 31, 2024, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/417; The Museum of Modern Art, “German Expressionism Techniques,” accessed May 31, 2024, https://www.moma.org/s/ge/curated_ge/techniques/index.html. German Expressionist Prints (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1995).

[4] Including expressionist art movements such as Die Brücke (1905-1913), Der Blaue Reiter (1912-1914), reactions against expressionism such as New Objectivity (1923-1933), and the craft and fine art Bauhaus movement (1919-1933)

[5] Sarah Suzuki, “Jean Dubuffet,” The Museum of Modern Art, accessed May 31, 2024, https://www.moma.org/artists/1633.

[6] For instance, in 1937 Picasso made a set of 18 engravings, as a denunciation against Franco and the Spanish Civil War, printing 1000 editions.

[7] EL Lissitsky taught printmaking alongside Marc Chagall and Kazimir Malevich at the ‘people’s art school’ in Vitebsk, Belarus

[8] Jose Vasconcelos’ belief in accessible art for all inspired the 1920s muralist movement and modern printmaking, emphasizing community empathy and defining Mexican identity through affordable, quick, and widely understandable prints.

[9] Mark McDonald, “Printmaking in Mexico, 1900–1950,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 2016, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/prmx/hd_prmx.htm.

[10] “Social Realism Prints, Works on Paper and Multiples,” Printed Editions, Accessed May 31, 2024, https://www.printed-editions.com/art-movement/social-realism/.

[11] A series of far-left student occupation protests that challenged the social, political, and economic structures, including the authoritarian government, traditional educational system, and capitalist economy.

[12] “A Short History of the Poster,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed August 31, 2024, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/a-short-history-of-the-poster?srsltid=AfmBOopl2Miq37LgSOF-vVrAHyOItiJQyiHTZ165s_4F82PVlPG_zFkg.

[13] Art historian Zeina Maasri refers to this as translocal visuality

[14] MacPhee, Paper Politics; Zeina Maasri, Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut's Global Sixties, vol. 13 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

[15] Zoé Samudzi, “Dindga McCannon and the Fabric of the Black Arts Movement,” BlackStar Film Festival, Issue 004, Summer 2022, https://www.blackstarfest.org/seen/read/issue004/dindga-mccannon-zoe-samudzi/; Nigel Freeman, “The Art of the Harlem Renaissance, in Print and Plaster,” Swann Galleries, March 25, 2024, https://www.swanngalleries.com/news/african-american-art/2024/03/the-art-of-the-harlem-renaissance-in-print-and-plaster/.

[16]

Nancy Finlay, “American Printmaking in the Twentieth Century,” The Princeton University Library Chronicle

42, no. 2 (1981): 104–12, https://doi.org/10.2307/26402233; Harry Abrams, Impressions of the 20th Century: Fine Art Prints from the V&A Collection (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2001).

Comments on General History and Evolution of Printmaking: Part 2