Living between brutal wars and sanctions, Iraqi artists of the 1980’s generation produced art that echoed the political and historical events over the past four decades. The vicious cycle of war and destruction became a dominant theme in their work and in Iraq’s material culture. It is reflected in the experiences of Iraq’s artistic production from the 1990’s to present day. The 1980’s generation of Iraqi artists continued to produce work that is a powerful and poignant testimony to their experiences and humanity.

Often, their art presents a manifestation of their personal experiences, from their everyday lives to the intimate spaces they inhabited. Through their work, the 1980’s generation of Iraqi artists remind us that violence generates complexities on multiple scales, including the legacies and structures of colonialism, capitalist imperialism, and militarization, within which lies the delicate nuances of everyday life. They can be found in the intimate spaces of a household, memories, conceptions of communities, forgotten places, and the relationship we have with the land.

Prominent Iraqi artist Hanaa Malallah belonged to the ‘Generation of the 1980’s’ – a generation that experienced a series of crises in Iraq. The generation bore witness to: the Iran-Iraq war, which was fought from 1980 to 1988, with devastating human loss for both countries; the first Gulf War, fought from 1990 to 1991, between Iraq and a coalition of countries led by the United States, after Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990. This was followed by the United Nations imposing a series of comprehensive economic sanctions on Iraq, placed from 1990 to 2003. Amongst other issues, the sanctions limited Iraq’s access to cultural resources and made it difficult for artists to produce and exhibit their work. Eventually the sanctions were lifted in 2003, and the United States-led invasion and occupation ‘officially’ ended in 2011. This was followed by the infiltration of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), the group’s rapid territorial gain, brutally violent tactics including but not limited to mass executions and enslavement.

Malallah was born and raised in Iraq, amidst the unrest. Born in Thi Qar, southern Iraq in 1958, she moved with her family to the central city of Baghdad at the age of five. Graduating from the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad in the 1980’s, where she studied both painting and graphic design under artists Faik Hassan and Shaker Hassan Al-Said. She spent many years producing art that reflected her homeland and its people’s experiences, before leaving Iraq in 2006, during the height of societal unrest. She first moved to Paris and later received a fellowship at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London, where she currently resides.

Inspired by her upbringing, Hanaa Malallah’s artwork encompasses the everyday realities of war, exploring fragmentations, chaos, grief, and renewal, caused by destruction of spaces, cities, and society. Her work delicately and thoughtfully presents the complexities of violence and human existence. As Gordon states “even those who live in the direst circumstances, possess a complex and oftentimes contradictory humanity and subjectivity that is never adequately glimpsed by viewing them as victims or, on the other hand, as superhuman agents”1.

This dichotomy is often imposed on societies whose experiences are reduced to the status of mere victims, where their agency and self-determination is disregarded. Conversely, portraying them as superhuman agents placing unrealistic expectations and distancing them from their own humanity. Malallah’s art challenges these dichotomies by portraying the contradictions and complexities that exist within the state of destruction. She recognizes the capacity for both resilience and vulnerability, as well as challenges the orientalist characterization of a ‘backwards Middle East’ by the West.

Artists and the Making of the Modern Iraqi State

In the case of Iraq, war-making and war-enduring cannot be divorced from their past nor present day ramifications. Such impacts have extended across all aspects of people’s lives, memories, choices, and waves of displacement. Wars have long occupied the Iraqi people’s lives and imaginations. The making of the modern Iraqi state in 1921 by the colonial British Mandate was itself a conflict over land and resources, modernity, and nationalism, depending on expropriation and (re)producing inequalities2. At the same time, resistance, art, poetry, and the cultural spirit of Iraq had long been foundational to the modernist, nationalist, and leftist projects in its cities – particularly in the central city of Baghdad in the mid-20th century. The famous Iraqi-Palestinian writer and artist Jabra Ibrahim Jabra described a vibrant Baghdad’s cultural and artistic scene in the 1950’s and 1960’s:

“There were the young women who were itching for their freedom, and I knew many of them. There were the powers and short-story writers who were seeking to create new forms in everything they wrote. There were the painters who had returned from their study abroad and who, despite their small numbers, were able to create new theories for Arab art everywhere, out the expression of their experiences in line and colors”3.

In a newly independent Iraq, modernists were highly influenced by nationalist and anti-colonial sentiments. They contemplated alternative visions of the future, freedom, and modernity, challenging the liberal notions that had attempted to define them.

Even though most artists during the 1950s and 1960s were male, female artists also made significant contributions to cultural production and the creation of new social and political spaces. Informed by their historical context, artists were experimenting with new aesthetic and cultural expressions, as well as providing space and visions of freedom4. Coffee shops bustled with visual artists, architects, writers, and scholars who had gathered to drink coffee, discuss politics, and exchange philosophical ideas. The locations were also a cite of resistance where people would exchange hidden political messages – a practice that continues to exist in Iraq today5. The young modernists collectively formed associations and established formal institutions which supported their work and collaborations.

Shakir Hassan Al-Said and the Baghdad Group for Modern Art

One of the pioneering artists and philosophers of this period, Shaker Hassan Al-Said (1925-2004), played a significant role in shaping the Baghdad Group for Modern Art in 1951, alongside its founding member artist Jewad Selim (1919-1961). The group brought together extraordinary members like Lorna Selim, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Mahmoud Sabri, and Mohammad al-Husni. It also played a crucial role at institutionalizing art in postcolonial Iraq.

The Baghdad Group for Modern Art championed the concept of istilham al-turath, meaning ‘drawing inspiration from cultural heritage’ in Arabic. They proclaimed the emergence of a new school of painting that derived and drew from contemporary civilizations6. It encompassed various styles and schools of plastic art, along with the unique character of Eastern Civilizations. The group advocated the 13th century Mesopotamian school of painting, such as that of Yahia Bin Mahmoud Al-Wasiti’s7, as well as Islamic art, to serve as a foundation for modern art in Iraq, rather than relying on European art. Whereas previous art culture in Iraq had revolved largely around European models, the Baghdad Group positioned istilham al-turath, or ‘the inspiration of cultural heritage’, as the foremost guideline for the elaboration of Iraqi modern art.

Revisiting Akkadian empire and Sumerian civilization8 sources served two crucial purposes for Selim and his contemporaries. Firstly, it provided Iraqi artists with a model that was intrinsically ‘theirs’, originating from the work of their ancestors rather than that of Western artists. Secondly, it served to connect and use as a continuation of an ancient art form through the language and institutions of modern art. The members of the Baghdad Group argued that these sources were already modern masterpieces, “their abstract forms, simplified lines, and geometric emphasis laid the foundation for modern art thousands of years before Picasso ever held a paintbrush”9.

Shakir Hassan Al-Said’s influence on Hanaa Malallah

Al-Said’s art is representative of his rural upbringing and anti-colonial struggles. His nationalism, closely tied to his philosophical explorations, bridged the gap between modernity and heritage. Al-Said became an influential figure in Iraq’s modern art movement. He inspired and taught generations of Iraqi artists, amongst whom was Hanaa Malallah. In 1971, he founded the One Dimension Group, or Al bu’d al Wahad in Arabic, an art collective which reflects on time and space, particularly, the concept of eternity, al-Azal in Arabic, in relation to spirituality. Members of the One Dimension Group manifested their search for the spiritual in art through abstraction; art thus becomes an act of meditation rather than being simply a form of creation.

Figure 1. Shaker Hassan Al Said, The Number 30, 1985, @ DAF

Al-Said’s approach merged Mesopotamian and Islamic heritage, particularly the philosophical understandings of life and humanity rooted in Sufism – a mystical branch of Islam. This informed his artistic practice and his exploration of calligraphic forms. He was inspired by traditional Islamic calligraphy, which he believed was a powerful visual language that could connect the present to the past. Al-Said investigated the formal characteristics of Arabic letters, and the Eastern Arabic numerals such as in his work The Number 30 (fig.1). His work focused on creating a distinctive Iraqi identity in contemporary art, pushing artists to draw from their heritage and seek inspiration from it.

Malallah’s work builds upon Al-Said's legacy, while creating a distinct style and approach of her own. Like Al-Said, Malallah draws from the heritage of Mesopotamia and Islamic art, but also uses materials rooted and rooted in that heritage. Reflected in her PhD thesis, which focused on the philosophy of painting, her work continues to integrate philosophical and spiritual explorations of Mesopotamian heritage and the nature of existence. Her compositions utilize handmade paper, natural pigments, birds’ feathers, and traditional Iraqi calligraphy tools. Using these materials draws connections between the artist and traditions of the homeland, giving her work a sense of authenticity and depth.

In an interview with Art Asia Pacific, Malallah explained: “I feel a deep connection to the materials I use. I think they have their own stories to tell, and by using them, I’m connecting to a larger narrative of Iraqi history and culture”10. This connection to heritage materials is significant in art, particularly, in a postcolonial context, where the dominant narratives of the region and aesthetics are often Western-oriented11. By using traditional materials and techniques, Malallah points to transformations, contradictions, nuances, as well as reclaims the cultural heritage of Iraq, and asserts its importance in the contemporary world.

The Cyclical Nature of Life and Death: The Ruins Technique

Hanaa Malallah was amongst the artists and professionals who continued to live in Iraq during unprecedented social and economic transformations. Three years into the American-led occupation of Iraq, Saddam’s Baathist government collapsed in 2003. Due to economic depletion and infrastructural destruction12, civil unrest and sectarian tensions reached an all-time high. Malallah is delicately intertwined with these realities of war – her work is not merely impacted by them, it is actively rooted and inseparable from them.

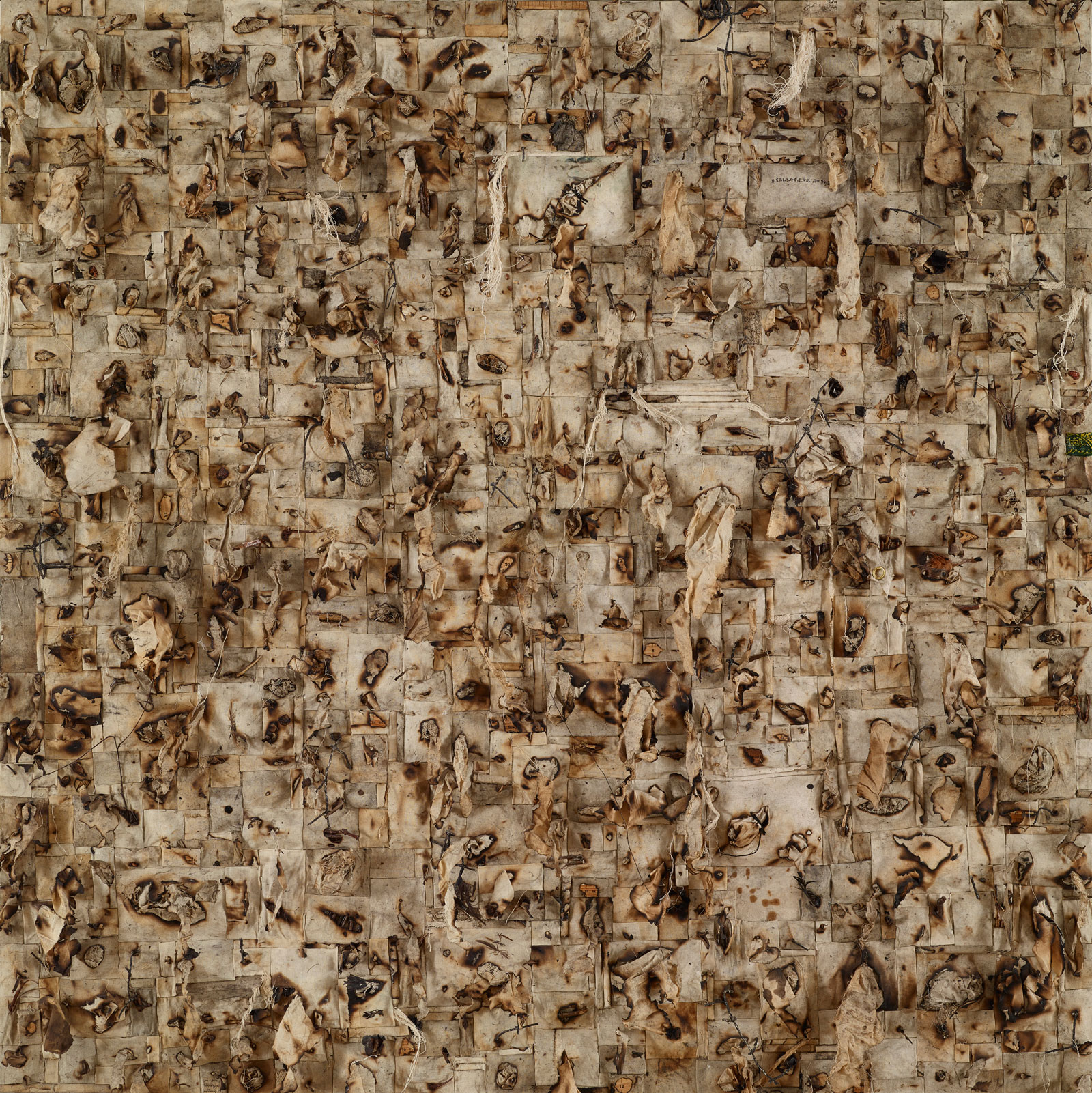

Through her artwork, Malallah engages in a dialogue with the social and physical devastation caused by conflict, with the scars of war prominently featured in every aspect of her creations. Her pieces serve as a reminder that the destructive power of war can reduce beauty to rubble, leaving nothingness in its wake. Living through Iraq’s past and present, Malallah developed the Ruins Technique, where she reincorporates raw materials found in war-scarred Iraq. In a 2016 interview conducted by Ruba Asfahani, Malallah stated “with this method I am not creating an image of ruins, but I am re-creating the process by which a material becomes a ruin”13.

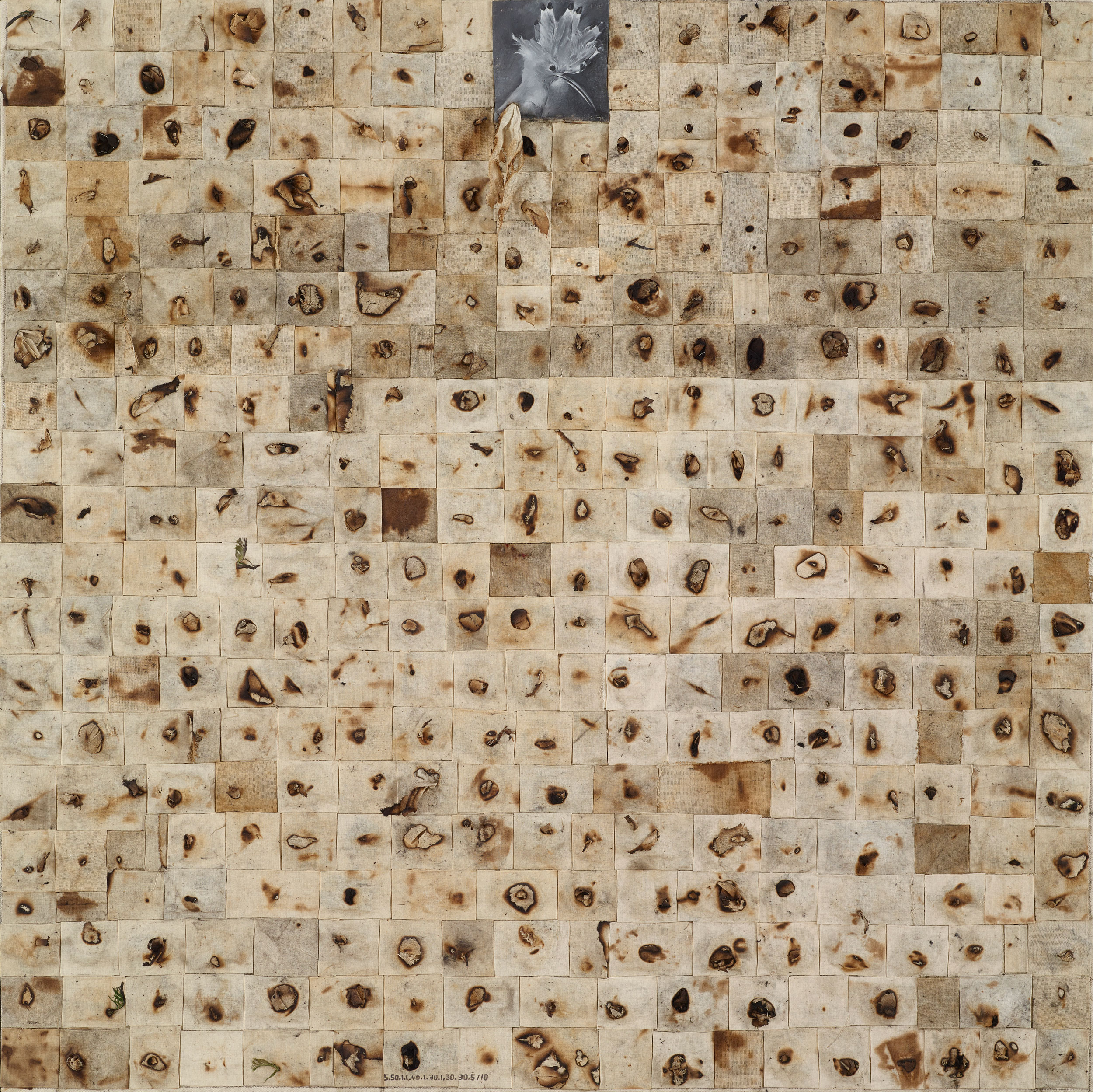

The Ruin’s Technique repurposes the materials, such as ones left behind by the destruction of places. Taking control of the material – a combination of wires, traditional handmade paper, natural pigments, and ropes – she burns, scratches, and combines it with the canvas’s material. The result is a palette of grey and brown colors, which appear lifeless yet earthy and loud, offering us a snapshot of the violence caused by the imperialist and capitalist destruction that had unfolded in Iraq.

Figure 2. Hanaa Malallah, Portrait (HOOPOE), 2010, @ DAF

Figure 3. Hanaa Malallah, Shroud V, 2012, @ DAF

Figure 4. Hanaa Malallah, Abstract Figurative, 2011, @ DAF

Malallah grapples with the intimate relationship between life and death as she reclaims the ruins of her homeland and recreates them into an indeterminate, interpretive piece of art. This is demonstrated in artworks such as: Portrait (HOOPOE), 2010, (fig.2), Shroud V, 2012, (fig.3) and Abstract Figurative, 2011, (fig.4) which are all part of the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF) in Beirut14.

With great detail, the technique leaves behind intricate figures, stains, and fragmentations that capture the essence of grief and chaos. These material and physical realities illustrate the hardships that individuals experience during and post war times, emphasizing that there is no sharp distinction between peace and war, nor between pre-war and post-war. Rather, echoes of destruction manifest through people’s everyday lives, affecting social and gendered relations, both in war and peace15.

Although Malallah’s art explores the destruction caused by war, it is not one-dimensional. Through the destruction she pushes us to recognize the generative aspects and the way death coexists with life. The dialectics of the Ruins Technique capture the fragility and beauty of life, even in the most violent of times. This theme is beautifully presented in her abstract piece Shroud V. ‘Shroud’ is a garment that is traditionally used to wrap dead bodies before burial, signifying the end of one stage of life and the beginning of another.

While the connection between shroud and women in Shroud V likely reflects the central role that women play in the process of mourning and remembrance, there is an underscoring theme of loss, grief, and trauma. The garment also signifies the cycle of life and rebirth. Women are the symbol of life, and birth, reproducing their communities not only in terms of reproduction through birth but also through their physical and emotional labour, particularly during times of unrest. This is showcased in the piece through the delicate lines and formation of obscured figures and faces.

Women often bear the disproportionate burden of caring for the wounded and mourning of the dead. In Iraq, for example, women have played a central role in mourning the many lives lost due to war and violence. Women have also borne the burden of economic depletion and social unrest, and faced significant psychological and social challenges as a result. In a New York Times article, Rubin quotes an Iraqi woman who described the ongoing conflict as a “never-ending funeral”16. Despite the manifestation of destruction on women’s lives, they have continued to play a vital role in their communities, as they re-produced and rebuilt – the ongoing contributions they make to the processes of life and rebirth through the everyday.

Figure 5. Hanaa Malallah, 17002 Landscape, 2014, @ DAF

The powerful realization that amidst death and grief, the everyday still unfolds is thoughtfully presented in Malallah’s painting 1700² landscape, 2014, at DAF, (fig.5) symbolizes the Camp Speicher massacre that took place in 2014, where 1,700 Shia cadets were massacred by ISIS17. It brings the process of grief to the forefront, where amid the destruction of the land and the death of Iraqi peoples, something else blooms, signified through red roses. Out of that grief and death, comes hope, revolution, or other visions of an indeterminate future.

Amidst the slaughter and deep pain, the cycle of life continues. The roses that consume the painting symbolize the continuation of life and the existence of people, their histories, and their hopes enduring within the rubbles of war. It is not merely a dead land – or a space that fosters sectarianism. Malallah’s artistry insists on representing the life and dignity of the people, bringing together the interconnectedness of land, politics, geography, and history together into art. This idea is reflected in Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry: “Upon this Land There is That Which Deserves Life; the hesitance of April, the scent of bread at dawn, an amulet made by a woman for men, Aeschylus’s work, the beginnings of love...”18.

Malallah shows us how destruction is the true face of war, and how the occupation of Iraq was not rooted in ideas of democracy nor freedom. Regardless of the reasons, the manifestation of war affects nature and societies, while always being informed by geopolitics. However, through Malallah’s art, the close relationship between life and death, and the normalization of this mode of necropolitical existence in the Iraqi experience, is challenged. Showcasing the cyclical relationship of life, where something ends and another begins, the technique provides a space for reflection. Viewers can explore the complexities of war and its impact on space or nature, and societies.

Confronting the violence of imperial and capitalist processes of accumulation and destruction is integral in bringing to light an alternative history. Malallah’s art attempts to accumulate history, and is a collection that stretches our understanding of art, destruction, and war. Using haunting as an invisible dialogue throughout her work, she aims to locate violence that possesses a long genealogy and historiography. Malallah confronts violence and what haunts Iraq, outside of both the forced ‘liberation’ imperial accounts, and beyond the ‘secular’ vs. ‘religious’ dichotomy that serves both imperial, capitalist, and fundamentalist religious projects.

Iraqi people’s narratives, art, poetry, and experiences are rich with emotional and material knowledge. They are rooted in both past and present, and illuminate on what fear, desire, hope, and resistance looks like. Their lives, collective struggles, and ways in which they conceptualize, navigate, and flow through violence challenges mainstream understandings of war, and of the Middle Eastern peoples. Malallah’s art and narrations show us the importance of a collective community’s knowledge production. Through her art, we can come to understand the making of the Iraqi State and its entanglements with violence – in the past, present, and future.

Hanaa Malallah carries the experiences of war with her and it goes beyond being a mere intellectual exploration. Rather, her art is an effort to translate the realities of destruction that are deeply intertwined with her personal experiences of war and displacement. Through her work, and in conversation with the past, she has developed a new philosophical vision around the sacredness of life and death. Iraqi bodies have become cheap and disregarded, in a process that violates the sacredness of death. Her work, particularly her Ruins Technique, involves a creative remaking of ruins into a new assemblage that tells a story of lives ensconced in loss. This makes her work different from abstract – for it brings the reality of life to art.

Edited by Wafa Roz & Elsie Labban.

Notes

Sources:

Comments on Hanaa Malallah's Art: Investigating Life and Death