Introduction: Bridging the Personal and Political

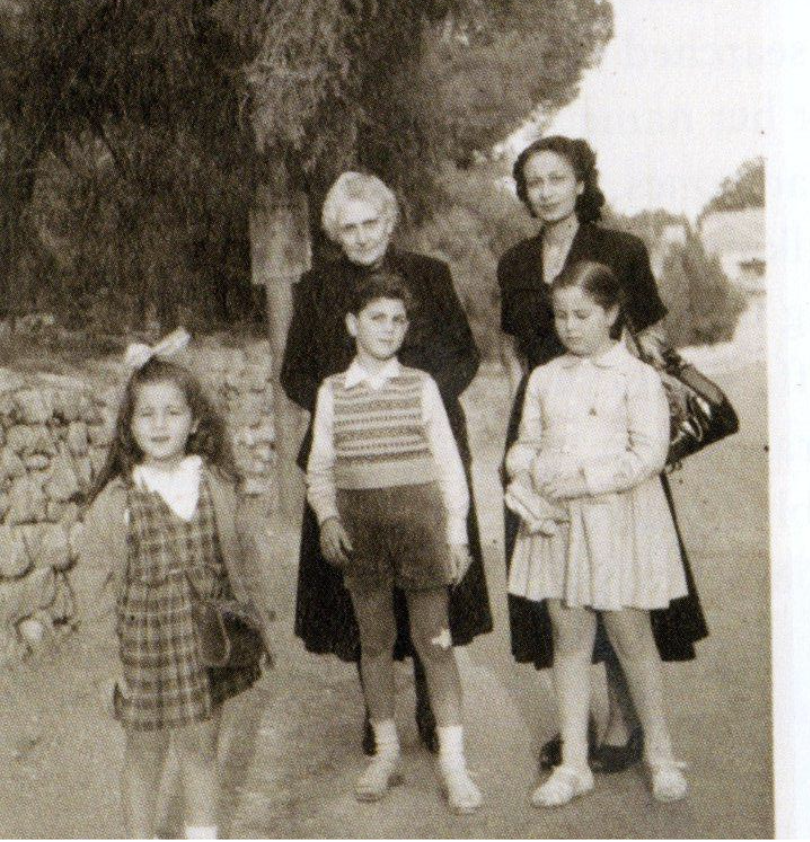

Vera Tamari, a Palestinian artist, educator, and curator, introduced a deeply personal perspective in her artistic portrayal of Palestinian identity. Born in Jerusalem in 1945, she experienced displacement during the Nakba, when her family was exiled from their ancestral home in Jaffa. Her work reflects the complexities of Palestinian identity through themes of exile, fragility, family bonds, and resilience, offering an intimate and personal counterpoint to broader narratives.

As a co-founder of the New Vision Movement, a collective formed after the First Intifada in 1987, Tamari played a key role in redefining Palestinian art. The New Vision Movement, which included Sliman Mansour, Nabil Anani, and Tayseer Barakat, sought to transcend traditional forms by embracing modern techniques and global art discourses while remaining rooted in Palestinian culture and politics. Central to their practice was the use of local materials like clay, wood, and natural pigments to ground their art in the land and heritage of Palestine instead of using imported material from Israel. While Palestinian art often used bold, nationalistic imagery tied to resistance, such as the incorporation of armed resistance, symbols like iron fists or barbed wire, elements like the cactus, or the olive tree, or Palestinian women in traditional garb, etc.; in response, the New Vision Movement explored and incorporated different languages and materials that could communicate their narratives with a broader public. Tamari’s contributions to the movement were distinctive in her focus on the intimate and familial aspects of Palestinian identity. Her work offered a deeply personal commentary on the intergenerational impacts of exile and the deep personal connections to homeland, blending universal themes with intimate narratives rooted in memory, family bonds, nature, and the land. Her preferred medium of ceramics, historically linked to women and domestic crafts, set Tamari apart from other Palestinian artists who predominantly worked with painting , thus positioning her as a pioneer in Palestinian ceramic art.

An innovator in ceramics, Tamari earned her master’s degree in Florence and established the first ceramics studio in the West Bank. She described clay as both a physical and spiritual extension of herself, fragile yet strong. Unlike painting, which is static, ceramics require direct interaction with material, reinforcing ideas of transformation and endurance. This reflects the broader Palestinian experience of displacement, adaptation, and perseverance.

Tamari’s artistic approach exemplifies the idea that the personal is political, a principle deeply resonant in the theoretical work of Whitney Chadwick, Lucy Lippard, and Griselda Pollock. Whitney Chadwick is an art historian and scholar known for her pioneering work in feminist art history, particularly through her book Women, Art, and Society, where she examines how women artists transform personal experiences into broader cultural critiques, asserting the importance of gender and identity in shaping artistic expression. This is evident in Tamari's work, where her reflections on family history and personal displacement become powerful tools of political commentary, embodying Chadwick's theory of the personal as political. Lucy Lippard is a renowned art critic, curator, and activist who developed the theory of materiality, suggesting that natural materials carry cultural memory. This theory deeply informs Tamari's use of clay, as the material becomes a symbolic conduit connecting her personal experiences with the broader Palestinian narrative of resilience and rootedness. Griselda Pollock, an art historian and cultural theorist, introduced the concept of "spaces of femininity," exploring how women reclaim spaces traditionally shaped by patriarchal narratives. Tamari embodies this in her transformation of domestic and natural spaces into acts of memory and resistance, asserting agency within both personal and cultural landscapes.

Chadwick’s theories highlight how Tamari’s intimate reflections on family and memory serve as powerful political statements against cultural erasure, positioning personal narrative as a form of resistance. Building on Chadwick’s theory that women artists use personal experience to critique societal structures, Lippard’s materiality theory suggests that natural materials carry cultural memory. Tamari’s use of clay physically and symbolically connects her to Palestinian history. Clay, shaped by external forces such as the hands of the artist, the heat of the kiln, and environmental conditions during its creation, yet retaining its inherent properties, mirrors the resilience of Palestinian identity. Despite being molded, fired, and sometimes weathered, clay maintains its essence, much like how cultural identity persists through displacement and adversity. Similarly, Pollock’s "spaces of femininity" theory explores how women reclaim spaces traditionally shaped by patriarchal narratives. Tamari transforms domestic and natural spaces into acts of memory and resistance.

By analyzing three of Tamari’s works, Oracles from the Sea, 1998, Tale of a Tree, 2002, and Emperors, 2014, through the aforementioned theoretical lenses, this article will demonstrate how her unique sensitivity and introspection contributed to a broader understanding of exile, displacement, and the enduring bonds between family and homeland.

Oracles from the Sea: Memory, Displacement, and Resistance

Tamari’s Oracles from the Sea, 1998, consists of sculpted clay faces that represent her ancestors, attached to metal rods and planted on the shores of Jaffa. These faces interact with the natural elements: wind, sand, and waves of the Mediterranean Sea, transforming the coastline into a living memorial. The term "living memorial" captures how the installation’s interaction with natural forces, such as erosion, weathering, and transformation, symbolizes the ongoing struggle to preserve Palestinian identity against forces of displacement and cultural erasure. Tamari described clay as a "malleable, still-forming material that solidifies into something unbreakable," a metaphor for the resilience of Palestinian identity in the face of displacement. She noted the risk-taking involved in working with clay, as pieces often break in the firing process or in their transportation to exhibitions, reinforcing the precarity yet persistence of Palestinian heritage.

The installation exemplifies how Tamari’s work reflects her deeply personal perspective on displacement and resilience by embodying her emotional and familial connection to her ancestral homeland, Jaffa. Although physically separated from Jaffa at only three years old, the stories of her homeland passed down by her family sustained her connection. In Oracles from the Sea, Tamari intertwines these personal memories with broader collective experiences of displacement, symbolically reconnecting her ancestors to their homeland and reaffirming her own enduring connection.

Lippard’s exploration of earthy materials as vessels of cultural and spiritual significance offers a valuable framework for understanding Tamari’s use of clay. Lippard emphasizes that materials like clay are not just passive mediums but active carriers of meaning, embedded with the histories, environments, and cultures from which they originate. In her view, natural materials extracted from one's land have an inherent narrative quality, capable of embodying memory, identity, and socio-political context. Tamari explained that while sometimes she imported her clay, she always associated it with Palestinian mud and earth, reinforcing her deep-rooted connection to the landscape.

The clay made faces’ placement along the coastline is particularly poignant. As they weather and erode, they reflect the ever-changing yet enduring connection between Palestinians and their homeland. This interplay between permanence and impermanence mirrors the dynamic struggle for cultural and historical preservation. Through this materiality, Tamari not only honors her ancestors but also asserts the resilience and strength of Palestinian heritage, redefining the shoreline as a symbolic space of resistance, memory, and reclamation.

Challenging the traditional boundaries of political expression, Chadwick's concept of the personal and domestic as potent arenas for resistance offers a profound lens through which to interpret Oracles from the Sea. Rather than relying on overt symbols of political defiance, Tamari infuses her work with intimate, everyday experiences, transforming personal histories into powerful acts of resistance. By centering her family’s narratives of exile and loss, she redefines the domestic not as a private retreat but as a critical space for political engagement. Her use of clay, a material rooted in domestic craft and historically dismissed as feminine, further amplifies this resistance. Tamari reclaims this "feminine" medium, elevating it to convey deeply personal yet universally resonant stories of displacement and resilience, thus blurring the lines between the personal and the political in profoundly transformative ways.

Pollock’s "spaces of femininity" theory further enhances our understanding of Tamari’s placement of the work in Jaffa. Pollock argues that women artists often incorporate spatial elements informed by their gendered experiences, embedding their works with layers of personal and collective meaning. By situating her work in public and contested spaces like the Jaffa coastline, Tamari reclaims these sites from political narratives, infusing them with personal histories that challenge dominant patriarchal and colonial discourses. By placing the fragile yet enduring clay faces in the natural environment of Jaffa, Tamari transforms the coastline into a living testament to resilience and cultural survival.

The personal dimension of Oracles from the Sea deepens when considered alongside the story of Tamari’s grandmother, Adele Zarifeh, as recounted in her book Returning. Adele, displaced during the Nakba, was buried in Damascus, far from her beloved Jaffa. Tamari reflects on the profound alienation Adele must have felt, resting in a cemetery surrounded by unfamiliar family names, disconnected from her community and roots. Tamari also recalls her own sense of dislocation during her visit, feeling out of place far from Jaffa and the familial ties that once centered their lives. This experience amplifies the emotional depth of Tamari’s work, as it not only honors her grandmother’s memory but also addresses a shared familial struggle. Adele’s story is emblematic of a broader reality: Tamari’s immediate family has graves scattered across Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Morocco, and Australia, with none in Jaffa, the land that once united them. In Oracles from the Sea, Tamari symbolically returns her ancestors to their rightful home. This act of remembrance transforms personal grief into a universal narrative of resilience and survival, underscoring the enduring struggle to maintain cultural and familial connections despite displacement.

The oracle, a central motif in the installation, intertwines femininity with ancestral wisdom. In many cultures, oracles are depicted as women, vessels of insight and connection to the divine. Through her work, Tamari assumes the role of preserver and transmitter of familial and cultural memory. The clay faces function as oracles, embodying the stories and resilience of Tamari’s ancestors while engaging in an ongoing dialogue with the land and environment. This interplay highlights the centrality of women in maintaining and passing on cultural identity. By positioning these faces along the shores of Jaffa, Tamari elevates her ancestors as custodians of history and culture, while simultaneously positioning herself as their contemporary counterpart.

Rather than serving as a mere backdrop, nature plays an active role in Oracles from the Sea. The interaction between the clay faces and natural elements, wind, sand, and sea, reflects the evolving relationship between people and their environment. This dynamic symbolizes the inseparable bond between Palestinians and their homeland. The faces appear to “communicate” with their surroundings, becoming part of the landscape rather than separate from it. By using materials that respond to nature, Tamari creates a sense of continuity, reinforcing the idea that the land itself carries the stories of the displaced. This underscores the permanence of memory and identity, even amid exile.

Ultimately, Oracles from the Sea is both an artistic and political act of reclamation. By embedding the likenesses of her ancestors in the shores of Jaffa, Tamari asserts ownership of a land that has been physically and symbolically taken from her. The work resists the erasure of Palestinian history and identity, transforming the coastline into a space of collective memory and resilience. Drawing on the theories of Whitney Chadwick, Lucy Lippard, and Griselda Pollock, Tamari’s focus on intergenerational memory, the personal as political, and the transformative power of materials offers a distinct perspective on exile and return. The installation exemplifies the potential of art to navigate complex histories, reclaim lost spaces, and challenge dominant narratives.

Emperors: Deconstructing Power through Fragile Forms

While Oracles from the Sea draws on personal memory and ancestral connection to reclaim a sense of belonging, Emperors, 2014, turns outward, offering a critique of how power is constructed, mythologized, and visually sustained. Together, these works reflect Tamari’s dual impulse: to recover what has been erased and to question the structures that enforce that erasure. If Oracles from the Sea is an act of return, Emperors is an act of deconstruction.

The installation consists of 100 miniature terracotta busts mounted on white resin cylinders. These are not dignified representations of rulers, but caricatured and grotesque figures: some smirking, others staring blankly. They are not rendered with grandeur, instead they appear exaggerated and theatrical, exposing the illusion behind political authority. Tamari does not depict these figures as specific individuals, but as symbolic echoes of leadership across time. In doing so, she shifts attention away from individual rulers toward a broader reflection on how power is visually encoded and perpetuated.

Tamari’s use of clay is central to this critique. Lucy Lippard argues that natural materials, like clay, are not neutral, rather, they carry cultural associations and histories. Clay is earthly, organic, and shaped by the hand, it resists permanence. While rulers may attempt to inscribe their legacies in stone or bronze, Tamari reminds us that power, like clay, is mutable, vulnerable to time, circumstance, and rupture. The material becomes metaphor: political power may appear solid, but it is always provisional, shaped by external forces and ultimately breakable.

Chadwick’s discussion of how women artists often transform personal experience into a lens for rethinking power structures offers insights into Emperors. While this work may not appear personal at first glance, its foundation lies in Tamari’s lived experience under occupation and her awareness of how authority is enacted and remembered. By avoiding specific likenesses, Tamari presents leadership not as individual, but as a repeated visual type, endlessly reproduced, stripped of character, and exposed in its theatricality.

Griselda Pollock’s concept of “spaces of femininity” further enhances our reading of Emperors. Pollock emphasizes that women artists often define how we experience and interpret space, not through grand statements, but through shifting the frame. Tamari does this by altering scale and perspective: Emperors is not a monumental display, but a dense field of small forms, each stripped of authority. Their repetition, uniformity, and fragility remove the aura of command. The display becomes not a place of tribute, but a place of reflection, a site where the viewer must confront how images of power are constructed.

Tamari’s pedagogical practice also resonates here. During her two decades as an architecture professor at Birzeit University, she fostered critical thinking among students, urging them to engage with materiality and meaning beyond aesthetics. One of her signature teaching exercises involved using frames with cut-out centers as windows to focus on specific details within the Palestinian landscape. By isolating sections of the environment, textures of stone, shifting light on terraces, or the organic patterns of tree branches, students learned to see with greater intention. But observation was only the first step: Tamari encouraged them to take what they saw and manipulate it, transforming their focused study into creative reinterpretations. This emphasis on deconstructing, reconstructing, and questioning dominant narratives also informs Emperors. Rather than merely portraying rulers, she dismantles their authority, uncovering the fragility and deception that sustain power while urging viewers to contemplate its inevitable rise and fall.

In Emperors, Tamari offers a slow and deliberate dismantling of how power is constructed, visually, materially, and historically. Through the use of clay and repetition, she questions the idea of permanence, showing instead how authority is subject to distortion, erosion, and loss.

Tale of a Tree: Loss and Renewal through Feminine Perspective

Tamari’s Tale of a Tree, 2002, blends personal grief with collective resistance, responding to the widespread destruction of olive trees during the Israeli incursion in Ramallah. The installation consists of 660 miniature terracotta trees, each representing an uprooted olive tree, arranged beneath a photo-transferred image of an olive tree on plexiglass. Olive trees, central to Palestinian culture, symbolize resilience, rootedness, and continuity. Their deep roots and long lifespan are metaphors for the steadfastness of the Palestinian people in the face of displacement. Beyond their symbolic power, olive trees are vital for Palestinian livelihoods, with olive oil production playing a critical role in trade and sustenance. Tamari’s choice to focus on this culturally significant tree reinforces the connection between people and the land, making its destruction both a personal and collective tragedy.

Continuing her exploration of displacement and resilience, Tamari uses the olive tree, a powerful symbol of Palestinian identity and livelihood, to express not only loss and endurance but also hope. She revealed in her interview that she crafted each miniature terracotta tree in Tale of a Tree while under curfew, sneaking out to her underground workshop after the Israeli tanks passed. Each piece, shaped by her own hands, was an act of defiance and preservation, reinforcing the artwork as both a personal and political statement.

As Chadwick suggests, women artists often transform personal experiences into acts of resistance, using intimate themes to confront broader societal and political issues. Tamari’s work embodies this approach, turning her personal sense of loss into a powerful statement against the erasure of Palestinian identity and heritage.

Tamari’s choice of terracotta as her medium is deeply meaningful, because it embodies both a symbolic and material connection to the land, reflecting themes of endurance, memory, and resilience central to her work. Lippard highlights how earthy materials like clay evoke memory and cultural connection. Terracotta, tied intrinsically to the land, mirrors the duality of fragility and resilience. While delicate and easily broken, fired terracotta achieves a lasting permanence, much like the endurance of Palestinian heritage despite efforts to uproot it. The pastel hues of the miniature trees add another layer of meaning, symbolizing hope amidst destruction. By placing these fragile, handcrafted sculptures beneath the image of a full-grown olive tree, Tamari bridges the physical devastation of the land with its potential for renewal, suggesting that hope and regeneration remain possible.

Tamari’s engagement with the olive tree motif highlights its nurturing and enduring qualities, aligning it with themes of care and regeneration. She describes olive trees as "motherly, sensuous figures," emphasizing their nurturing role in Palestinian heritage. Like mothers, olive trees sustain, protect, and provide, embodying qualities of care and resilience. Tamari’s language of motherhood highlights the tree’s symbolic connection to life, strength, and endurance, much like a mother sustaining her family through adversity. Her depiction of olive trees as "storytellers" and "twirling slowly in [...] a Sufi trance" emphasizes their role as witnesses to history, bearing the weight of collective memory while continuing to thrive despite displacement and destruction. Tamari also noted that Palestinian women have historically been central to preserving cultural heritage, from craft traditions to contemporary art. This preservation extends beyond artistic expression to encompass the safeguarding of collective memory, identity, and resistance against cultural erasure. Palestinian women’s contributions to embroidery, basket weaving, and pottery were crucial in maintaining Palestinian identity. Tamari’s own ceramic practice can be seen as a continuation of this tradition.

Through her artistic process, Tamari assumes the role of a mother herself, shaping each of the 660 miniature trees with care and intention. This labor-intensive creation reflects maternal values of care, preservation, and protective love for her homeland. Her connection to nature was ingrained in her from childhood, as her mother encouraged her to look closely at colors and textures in the Palestinian landscape. This meticulous attention to detail shaped her artistic approach, where every tree, every fingerprint on the clay, carried an emotional weight. By crafting these delicate trees, she positions herself not just as an artist but as a custodian of Palestinian heritage, reclaiming the spirit of the land through her art. By shaping each tree herself, Tamari mirrors the maternal qualities of the olive tree, transforming personal loss into a broader narrative of renewal and resistance, emphasizing the importance of nurturing and preserving cultural identity in the face of its destruction.

Conclusion:

Vera Tamari’s art exemplifies the transformative power of blending personal and collective narratives. By focusing on themes of exile, memory, and resilience, she challenges dominant political structures and reclaims Palestinian identity through deeply intimate and personal perspectives. Her use of earthy materials such as clay and her depictions of ancestral and natural connections underscores the enduring bond between people and their homeland, resisting erasure and asserting continuity. Tamari affirmed that Palestinian women have played a crucial role in preserving cultural heritage, from craft traditions to contemporary art. She viewed herself as part of this lineage, preserving memory and history through her ceramic practice.

Analyzed through the lenses of theories articulated by scholars focused on female art, Tamari’s work transforms private grief and familial bonds into universal statements of resilience. As both an innovator and a custodian of heritage, Tamari bridges the gaps between past and present, personal and collective, individual and universal, positioning her as a vital voice in Palestinian art discourse.

Notes

1 Wafa Roz, "Vera Tamari," Dalloul Art Foundation, 2018, accessed December 30, 2024, https://dafbeirut.org/en/vera-... Samar Kadi, "How Palestinian Art Evolved under Siege," The Arab Weekly, May 12, 2019, accessed December 30, 2024, https://thearabweekly.com/how-... Ibid.

4 Vera Tamari, interview by Aliya Beyhum, January 23, 2025.

5 Rose Courteau, "Vera Tamari’s Art of Resourcefulness," Family Style, February 12, 2024, accessed December 30, 2024, https://www.family.style/slow-... Vera Tamari, interview by Aliya Beyhum, January 23, 2025.

7 Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art, and Society (London: Thames & Hudson, 1990).

8 Lucy Lippard, The Pink Glass Swan: Selected Essays on Feminist Art (New York: New Press, 1995).

9 Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity, and the Histories of Art (London: Routledge, 1988).

10 Vera Tamari, interview by Aliya Beyhum, January 23, 2025.

11 Lucy Lippard, The Pink Glass Swan: Selected Essays on Feminist Art (New York: New Press, 1995).

12 Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity, and the Histories of Art (London: Routledge, 1988).

13 Vera Tamari, Returning: Palestinian Family Memories in Clay Reliefs, Photographs and Text (Arab Image Foundation (AIF) and Educational Bookshop, 2022), 30.

14 "[Palestine] Vera Tamari / Yazid Anani (Eng)," YouTube video, November 14, 2017, accessed December 30, 2024, https://youtube.com.

15 Lucy Lippard, The Pink Glass Swan: Selected Essays on Feminist Art (New York: New Press, 1995).

16 Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art, and Society (London: Thames & Hudson, 1990).

17 Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity, and the Histories of Art (London: Routledge, 1988).

18 Vera Tamari, interview by Aliya Beyhum, January 23, 2025

19 Vera Tamari, interview by Aliya Beyhum, January 23, 2025.

20 Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art, and Society (London: Thames & Hudson, 1990).

21 Lucy Lippard, The Pink Glass Swan: Selected Essays on Feminist Art (New York: New Press, 1995).

22 Penny Johnson and Anita Vhullo, eds., Intimate Reflections: The Art of Vera Tamari (A. M. Qattan Foundation, 2021), 10.

23 Penny Johnson and Anita Vhullo, eds., Intimate Reflections: The Art of Vera Tamari (A. M. Qattan Foundation, 2021), 10.

24 Vera Tamari, interview by Aliya Beyhum, January 23, 2025.

25 Vera Tamari, interview by Aliya Beyhum, January 23, 2025 .

26 Vera Tamari, interview by Aliya Beyhum, January 23, 2025.

27 Vera Tamari, interview by Aliya Beyhum, January 23, 2025 .

Sources

Ankori, Gannit. Palestinian Art. London: Reaktion Books, 2006.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. London: Thames & Hudson, 1990.

Creative Palestinian Art: Competition, Exhibition, Publication. Dubai: Art Sawa, 2010.

Courteau, Rose. "Vera Tamari’s Art of Resourcefulness." Family Style, February 12, 2024. Accessed December 30, 2024, https://www.family.style/slow-burn/vera-tamari-palestine-art.

Friends of Birzeit University (FOBZU). "Land, Memory and Belonging: A Conversation about Art and Education in Palestine with Vera Tamari." YouTube video, July 6, 2023. Accessed December 30, 2024. https://youtube.com.

Johnson, Penny, and Anita Vhullo, eds. Intimate Reflections: The Art of Vera Tamari. A. M. Qattan Foundation, 2021.

Kadi, Samar. "How Palestinian Art Evolved under Siege." The Arab Weekly, May 12, 2019. Accessed December 30, 2024. https://thearabweekly.com/how-palestinian-art-evolved-under-siege

Lippard, Lucy. The Pink Glass Swan: Selected Essays on Feminist Art. New York: New Press, 1995.

Moberg, Ulf Thomas. Palestinian Art. Stockholm: Cinclus, 1998.

Pollock, Griselda. Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity, and the Histories of Art. London: Routledge, 1988.

Roz, Wafa. "Vera Tamari." Dalloul Art Foundation, 2018. Accessed December 30, 2024. https://dafbeirut.org/en/vera-tamari.

Tamari, Vera. Interview by Aliya Beyhum, January 23, 2025.

Tamari, Vera. Returning: Palestinian Family Memories in Clay Reliefs, Photographs and Text. Arab Image Foundation (AIF) and Educational Bookshop, 2022.

"[Palestine] Vera Tamari / Yazid Anani (Eng)." YouTube video, November 14, 2017. Accessed December 30, 2024. https://youtube.com.

Voskeritchian, Taline. "Vera Tamari’s Lifetime of Palestinian Art." The Markaz, October 16, 2023. Accessed December 30, 2024. https://themarkaz.org/vera-tamaris-lifetime-of-palestinian-art/.

Zaki, Rula Alami, and Charles Pocock, eds. Art Palestine: Nabil Anani, Tayseer Barakat, Sliman Mansour. Dubai: Meem Gallery, 2011.

Comments on Lines of Memory, Layers of Clay: Vera Tamari’s Personal and Political Landscape