The journey of Lebanese theater, just as any cultural art form, did not emerge in a vacuum. Understanding its roots requires delving into the broader Arab world. The turn of the 20th century witnessed a renaissance in Arab theater. Arabic drama, while borrowing elements from Western theatrical traditions, started to develop a distinct style and language. Productions of Shakespeare and Molière were re-contextualized for Arabic audiences, laying the foundation for an era of rich theatrical experimentation in the region. The Lebanese theater scene was instrumental in this development, as pioneers like Mounir Abou Debs, Antoine Moultaka, and Jalal Khoury, to name a few, played a pivotal role in shaping modern Arab theater.

Renaissance: Arabic Theater from Beirut to Cairo

Amidst this surge of interest and cultural renaissance, there is a debate that underlies the history of Arab theater. While some renowned figures in the Arab world argue against the existence of a pre-mid-19th century Arab theater, others contend that the roots of Arab drama can be traced back to ancient traditions and practices. Arab intellectuals like Egyptian literary critic Abbas Mahmud al-Aqqad, Egyptian novelist Najib Mahfouz, and scholar Muhammad Mustafa Badawi discard the theory that an Arab theater existed before the mid-19th century. Others, such as theater art critic Ali al-Rai, drama professor Ibrahim Hamada, and Arabic literature professor Shmuel Moreh, believe that there were elements of dramatic manifestations in the Arab literary heritage. These include folktales (al-Hakawati), shadow plays (khayal al-zill)or mourning rituals (al-Ta’ziyah). Other informal performances included folkloric celebrations and farces. One thing for sure is that before the mid-19th century, Molière, Sophocles, and Shakespeare were strange to the Arab public.

It seems that the Arabic theater, we know today, emerged in the mid-19th century. It began with drama transformation after Aristotelian theater came to the Arab world with commissary voyagers returning from Europe. Following the model of prominent European playwrights, theater performances were staged in private circles and were based on literary texts.

Maroun Al-Naqqash, Abu Khalil Qabbani, and Ya'qub Sannu' were the three leading dramatists of 19th-century Arabic drama. They came from Greater Syria or Egypt. During the 1850s, Greater Syria included modern-day Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria. At the time, Egypt and Greater Syria were becoming centers for European cultural exchange and missionary education, especially in Beirut and Alexandria.

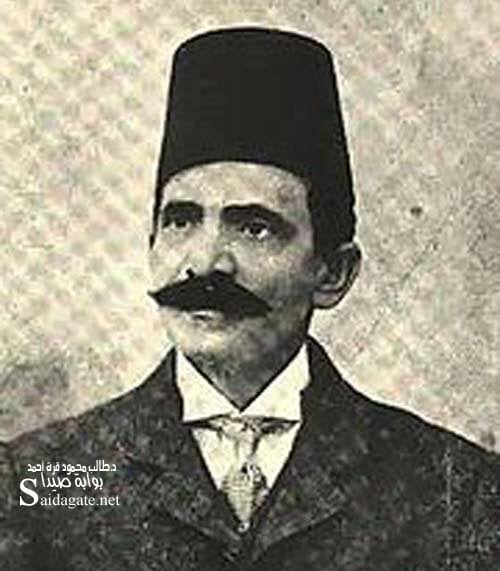

Maroun al-Naqqash, the first Arabic playwright, received his formal missionary education in Lebanon. Born in Sidon in 1917, Al-Naqqash moved to Beirut in 1925 and became a trader. He frequently traveled to Europe. During one of his journeys to Italy, in 1847, al-Naqqash became inspired by the Italian operetta, and wrote his first musical play, al-Bakhil. It was an adaptation of Moliere’s play L’Avare, meaning stingy. Al-Naqqash staged his play at his Beirut house, which was later transformed into a church. He introduced ninety popular musical rhythms, from across Lebanon and the region, into the play. The popular musical element which Al-Naqqash introduced in al Bakhil would later become a cornerstone of Arabic theater.

After his untimely death in 1855, Al-Naqqash’s brother Nicolas and his nephew Salim continued his legacy. In recognition of Maroun’s work, Nicolas wrote several Arab-history themed plays, such as al-Shaykh al-Jahil, al-Musi, and Rabi’a ibn Ziyad al-Muqaddam. As for Salim, he was widely received as a creative writer. Salim produced various adaptations of European plays like Pierre Corneille's Horace in 1868. His writings were widely circulated and more polished than those of his uncle. As a renowned advocate of Arabic theater, Salim and his troupe moved from Beirut to Cairo, to overcome the financial hurdles of running a theater in his home country. Moreover, the Khedive of Egypt provided a more flexible setting, allowing Salim to remain a key advocate of Arabic theater.

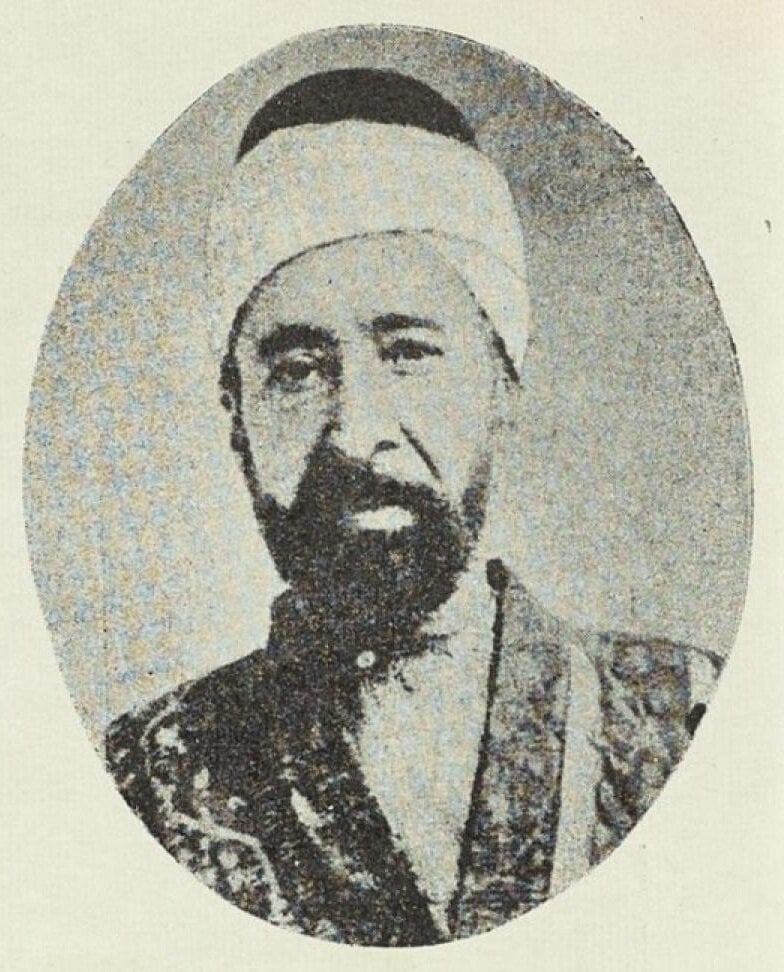

Another noteworthy dramatist of the late 19th century Arabic theater was the Syrian Abu Khalil Qabbani (1833-1902). Qabbani followed Salim Naqqash to Egypt, where he successfully directed several of his works and other playwrights' works. The third drama pioneer of the 19th century was Ya’qub Sannu’ (1839-1912), an Egyptian Jew. Sannu’ had a significant role in the Egyptian nationalist movement and was the founder of Egyptian theater.

.jpeg)

Nearing the end of the 19th century and after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, in WWI, Egypt regained its independence from the British in 1922, and became the pioneer of Arabic drama. It was not until the withdrawal of European powers from the region, that other countries would begin to see the revival of their own Arabic drama. Several distinguished playwrights and directors emerged outside of Egypt. The cultural exchange between the Arabic literary scene and western drama would continue over a long period, from the mid-19th century until the mid-20th century. This long exchange would have a considerable effect on Arabic drama.

Amidst the cultural exchange and transformative phase of Arabic drama in the broader region, Lebanon began to chart its unique trajectory in the theatrical realm. The nation's rich multilingual heritage and cosmopolitan spirit positioned it as a melting pot for theatrical experimentation and innovation. This transition was not merely about embracing Western influences, but rather about redefining and adapting these influences to resonate with the Lebanese identity and context.

Modern Theater in Lebanon

During the 1960s, Beirut was lively, filled with theater-makers and theatrical experimentation. The theater in Lebanon was active in four languages: Arabic, English, French, and Armenian. Work in the theater was initially based on European play adaptations and Classical Western drama translations. With time, it reached the growing Arabic literary market. Author Khaleda Said attributes the maturity of the Lebanese theater to the late 1960s. She explains, “the Lebanese theater matured after 1965, benefiting from the democratic atmosphere that existed at the time, which enabled it to diversify and develop.” Said defines the year 1965 as "a turning point" in Lebanese theater. After that year, three theaters opened: Theater of Achrafieh, Beirut Theater, and the National Theater. These openings coincided with establishing a School of Fine Arts at the Lebanese University (UL) with a specialized theater division.

However, the late 1950s and early 1960s were as crucial for the development of theater in Lebanon as the post-1965 era. In those previous years, individual initiatives led to the establishment of drama schools, art and theater movements, and modern art groups that paved the way for a generation of dramatists, theater directors, playwrights, art directors, and set designers. This earlier period of the late 1950s and early 1960s is best known through its theater-makers. The works and careers of several talented theater makers truly shaped theater in Lebanon as we know it today. These individuals included: Mounir Abou Debs, Antoine Moultaka, Jalal Khoury, Roger Assaf, Nidal Ashkar, and David Kurani. Each of these theater-makers (directors and playwrights) collaborated with several set designers, some of whom were visual artists. They opened up the world of theater to a burgeoning Beirut art scene. The theater-makers and their initiatives to build Lebanese Theater are not limited to the names presented. However, these five theater-makers, alongside the visual artists they collaborated with, and the drama institutes they founded, would later constitute the foundation of 1960s Lebanese theater. They would also come to be regarded as some of Lebanon’s key modernists.

The Baalbek International Festivals

Building upon this rich foundation set by these pioneering theater-makers, a significant landmark emerged in the mid-1950s that would further revolutionize the Lebanese theater scene: The Baalbek International Festivals. These festivals were the beginning of the era of theater in Lebanon. In 1956, President Camille Chamoun inaugurated the first Baalbek International Festival in the Roman temples of Northern Lebanon. It was said that the splendor of the Roman temples surrounding the festival would be a unique setting that can bring in cultural and economic capital into the country. The festival gathered hundreds of thousands of people every year, hosting renowned international artists and some of the best Lebanese theater groups. The festival continues to this day.

It should be noted that the Roman temples saw performances before the official establishment of the Baalbek International Festivals. In 1922, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis, by Georges Vayssie, was performed in French at the temple of Jupiter in Baalbek. The show was inaugurated by lawyer Charles Debbas, who later became President of Lebanon under the French mandate, from 1926 to 1933. Similarly, in 1944, The National Association for the Development of Lebanese Culture presented an adaptation of a tragedy by the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus titled The Persians, in French. The play was performed at the temple of Bacchus in Baalbek and inaugurated under the auspices of President Bechara El Khoury, the first president of independent Lebanon. Furthermore, before the Baalbeck Festival’s inauguration in 1956, President Camille Chamoun inaugurated four theatrical classics organized and performed by Jean Marchat’s troupe, in 1955.

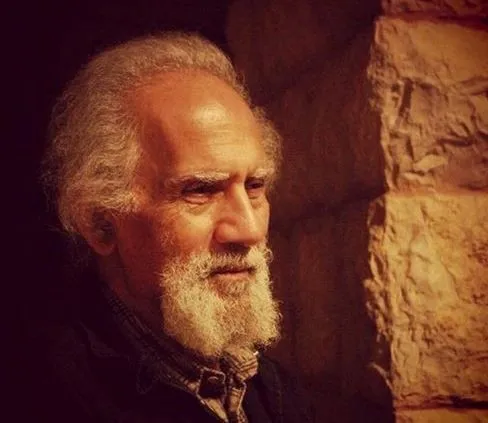

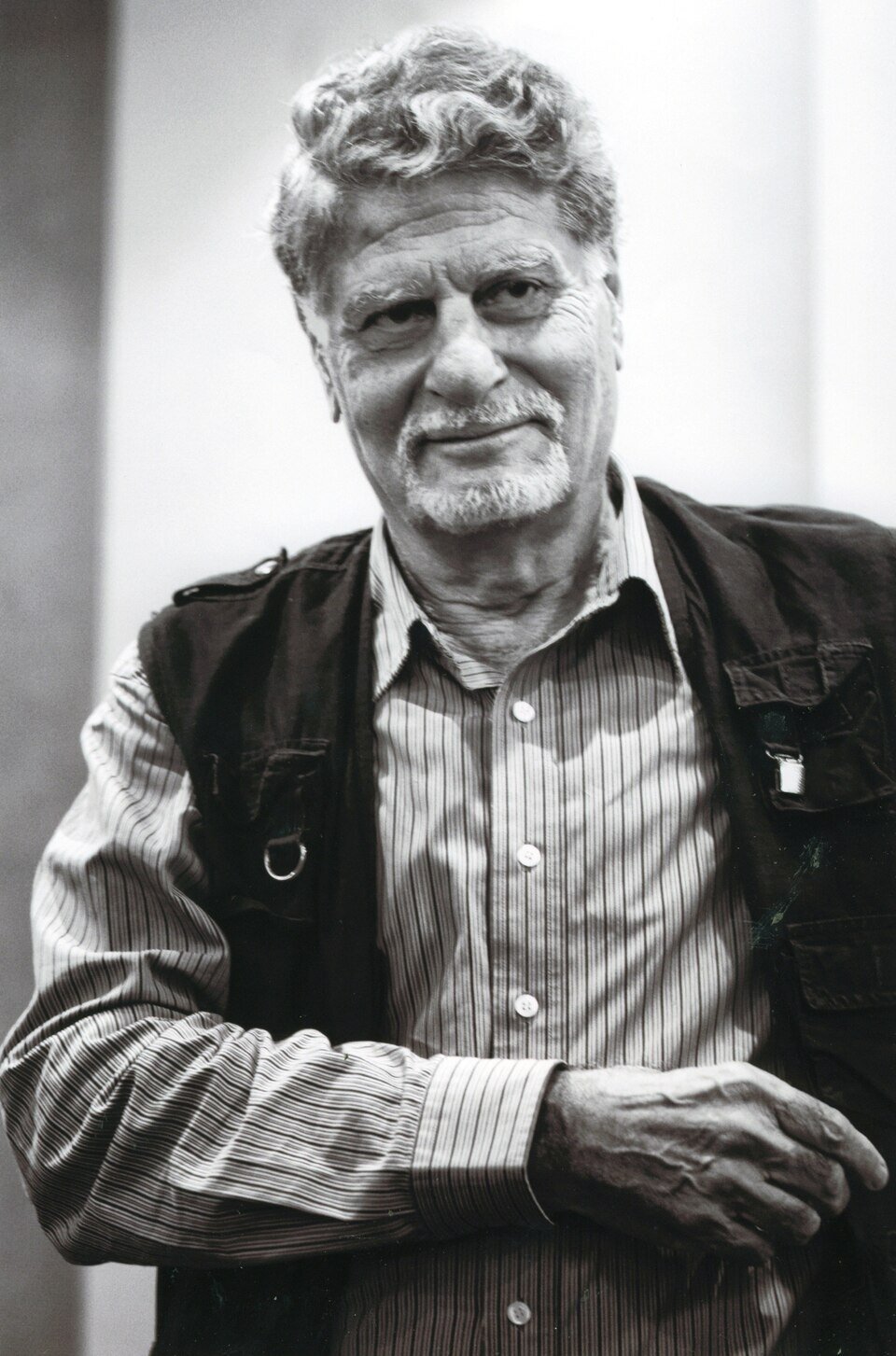

Mounir Abou Debs and The Modern Theater Group

Building on the rich tapestry of Lebanon's theatrical history, the contributions of individuals like Mounir Abou Debs stand as testaments to the country's continuous evolution in the world of drama and performance. Abou Debs (1932-2018) was a director and playwright who, with the help of key individuals who dominated the Baalbeck International Festivals, founded the “Modern Theater Group”, in 1961. Abou Debs worked on Arabic adaptations of western dramas, and along with other set designers, he particularly worked with painter Aref Rayess. In 1958, Mounir Abou Debs was working at the Office de Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (ORTF) in France, when he met engineer René Hury. Rene Hury was working on establishing the first television station in Lebanon through the ORTF, and asked Abou Debs to participate in the project. The Lebanese television station was established in 1959, as La Compagnie Libanaise de Télévision, later known as Tele Liban. In 1959, through the newly established Tele Liban, Abou Debs presented a weekly television play. Along with his old schoolmate, Antoine Moultaka, Abou Debs showed his first theatrical adaptation of Macbeth. Moultaka, a philosophy teacher back then, translated the script from English to Arabic and played Macbeth's role. His wife, Latifa Chamoun Moultaka, played the role of lady Macbeth. Abou Debs directed the play and staged it at the newly founded space of Télé Liban.

Following Macbeth's success, the famous Lebanese writer, and composer Assi al-Rahbani, asked Abou Debs to join the Rahbani Brothers' theater team. The Rahbani Brothers – Assi and Mansour – were composers, songwriters, authors, and dramatists who exercised a lot of power over the Baalbeck International Festivals. The Rahbani Brothers' musical plays were performed at Baalbek's temples during the Baalbek Festivals and almost always featured the legendary Lebanese singer Fairouz, Assi Al Rahbani's wife. They were revered by audiences across the Arab world and hailed as a symbol of Lebanese nationalism. Through the Rahbanis, Mounir Abou Debs became Lebanon's leading theater maker. Although Abou Debs and Moultaka started as partners, they then separated. Each went on to adopt a distinct approach to theater and play directing.

Mounir Abou Debs, who studied plastic arts, theater, and classic literature, worked with people from different artistic backgrounds. During his first visit to Lebanon, in 1959, Abou Debs met with several artists at Café La Palette, in Beirut. Some of these artists, such as Jalal Khoury, Antoine Moultaka, Latifa Moultaka, Madonna Ghazi, and Rida Khoury, later became significant to Beirut's theater scene. Abou Debs also encountered painter and sculptor Aref Rayess, whom he had befriended while in Paris. As a progressive and imaginative artist, Aref Rayess created the stage design of one of Abou Debs’s early plays, al-Izmil (The Chisel), written in Arabic by Lebanese playwright Antoine Maalouf. The play was first staged in West Hall at the American University of Beirut, in March 1964, then at the Bacchus temples of Baalbek during that same year.

Abou Debs believed that the development of theater must rely on proper, professional training. Therefore, he moved to institutionalize the practice. Salwa Said, the head of folklore at the Baalbeck Festivals, helped Abou Debs establish the Modern Theater Institute in 1959. Placed at the Daouk house in Ras-Beirut, the institute launched its classes in 1960, and in 1961, it was acknowledged as the first academic institution to teach drama in Lebanon. Along with Suad Najjar, Salwa Said, and Fouad Sarraf, Abou Debs co-founded the Modern Theater Group, a subsidize of the Baalbeck International Festivals. Within two years, cultural activist Janine Rubeiz, and the architect Wasek Adib, had joined the group. In 1967, Janine Rubeiz left the group to establish a cultural space that brought artists from different artistic backgrounds together. The space became known as Dar el Fan, or The House of Art.

Abou Debs continued to work under the management of the Baalbeck Festival until 1971. In 1976, he fled the Lebanese civil war, and went to Paris. Nearly two decades later, Abou Debs returned to Lebanon to revive his theater legacy. He opened a theater and a drama school at his newly renovated silkworm farm in his native village of Freikeh.

Antoine Moultaka and Le Cercle du Théâtre Libanais

.jpeg)

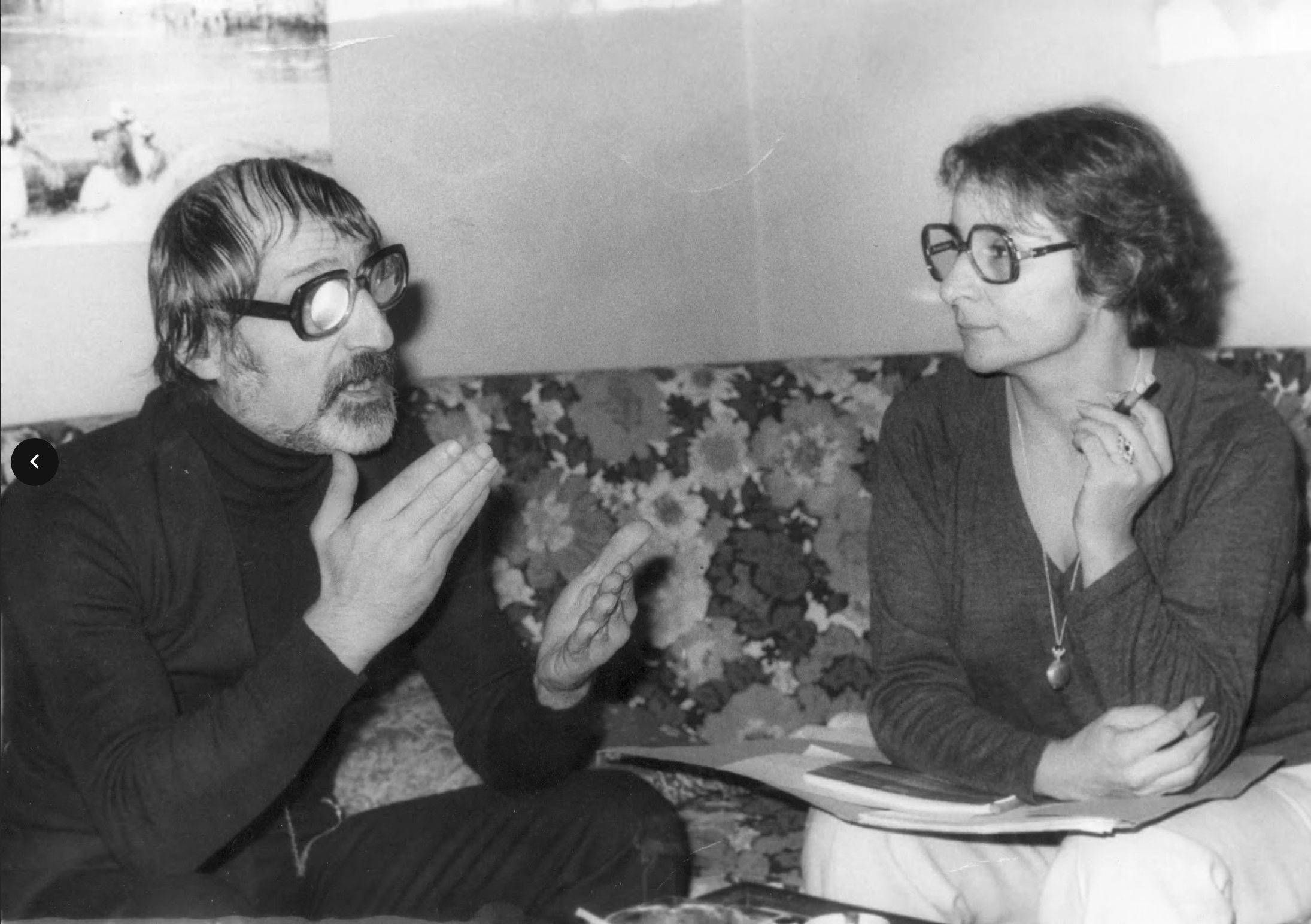

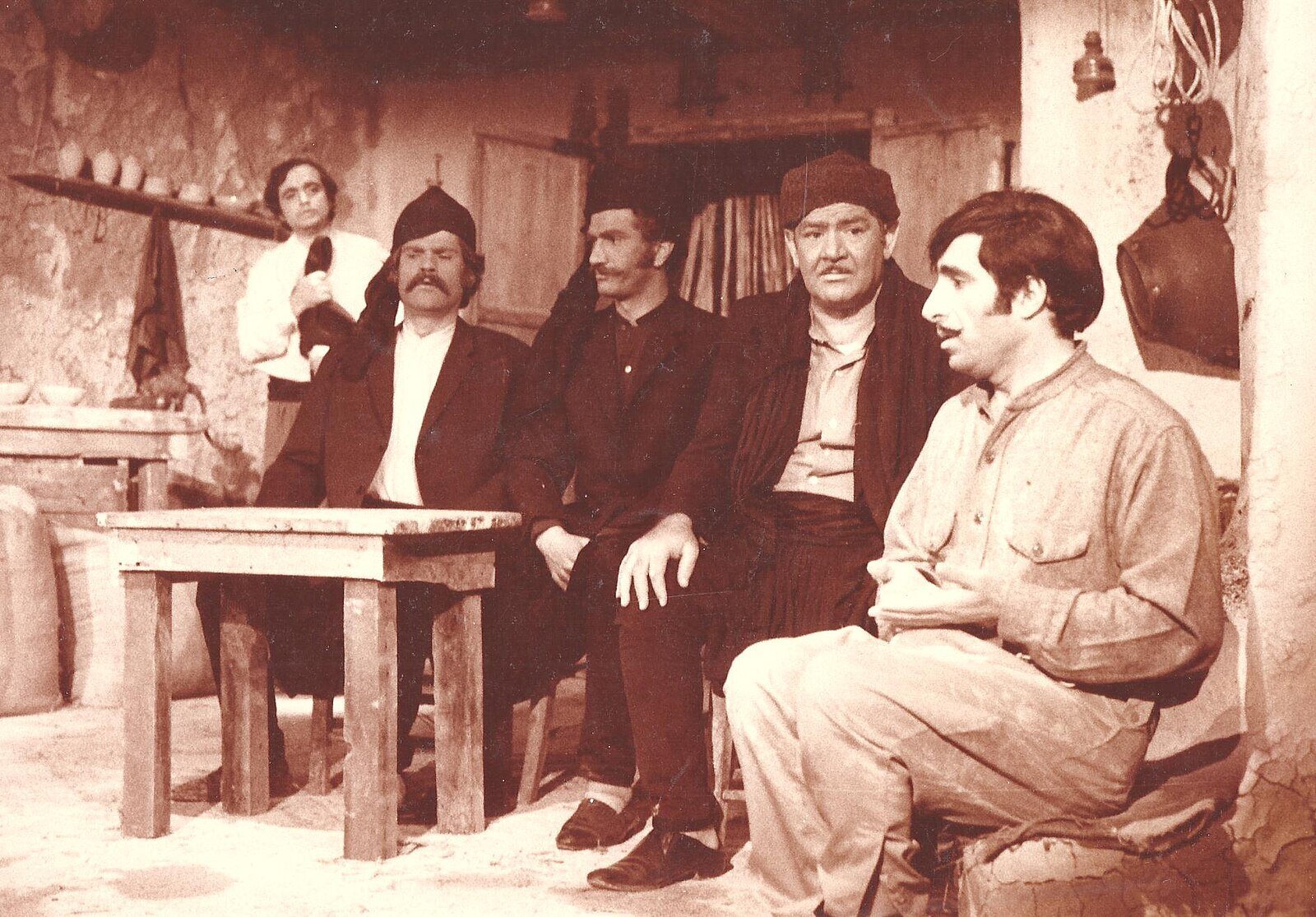

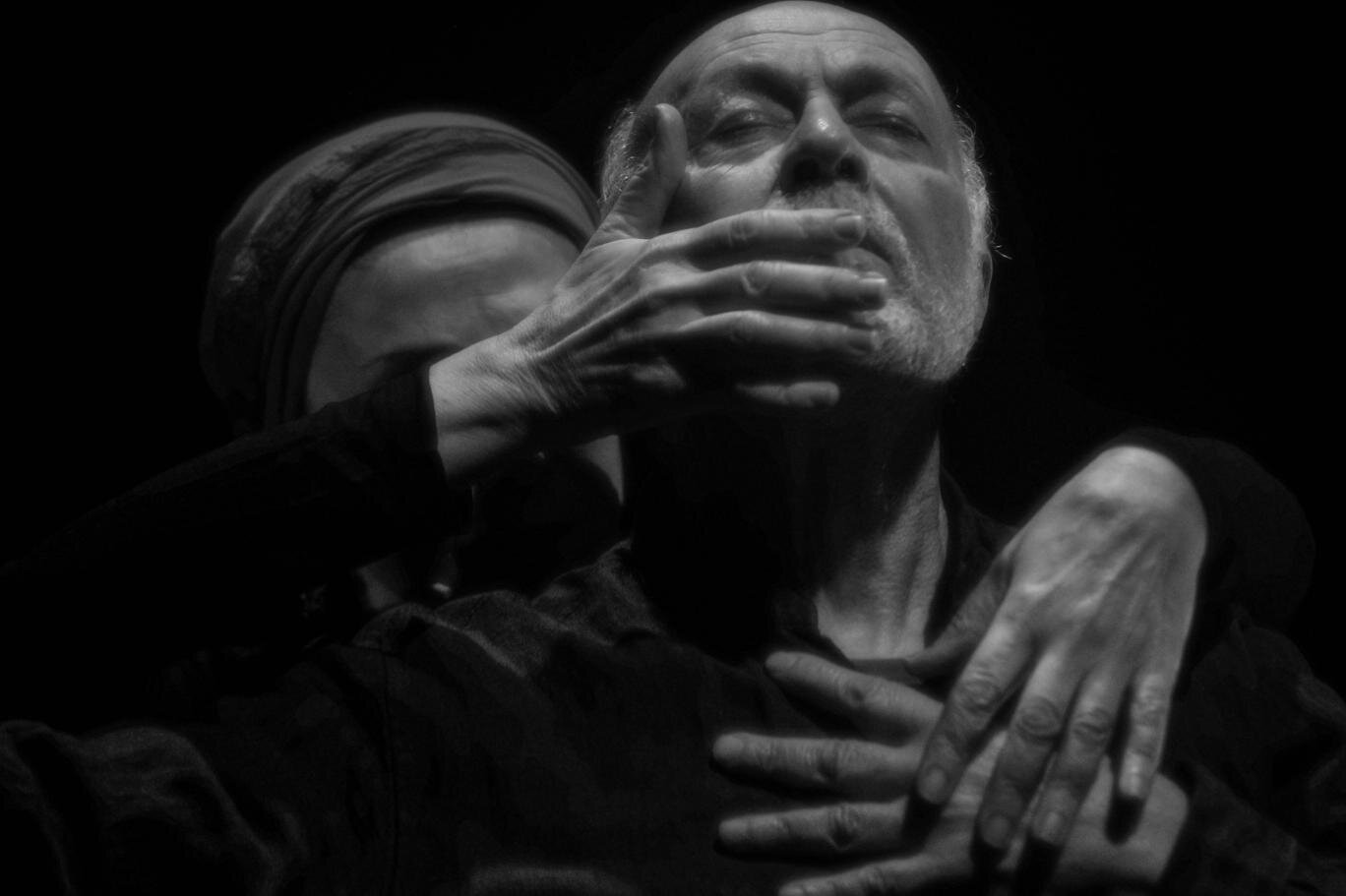

As mentioned earlier, Antoine Moultaka and Mounir Abou Debs began working as a team but then parted ways after Abou Debs formed the Modern Theater Group. Antoine Moultaka (b.1933) was a philosophy teacher and theater specialist. Like Abou Debs, Moultaka directed Arabic adaptations of classic western dramas such as those written by Sophocles and Shakespeare. However, Moultaka had a different approach to theater directing and theater production. While Abou Debs preferred taking command of what actors are supposed to do to achieve his vision, Moultaka concentrated on the actors and prized their individuality. He encouraged his actors to unleash their emotions and trained them in breathing techniques from Hatha yoga. His productions usually addressed themes that revolved around societal and psychological concerns.

In 1961, Antoine Moultaka co-founded Le Cercle du Théâtre Libanais (The Lebanese Theater Circle) with his wife Latifa Moultaka, sculptor Michel Basbous, author Edouard Amin al Boustani, Joseph Abu Chahine, and Francois Khoury. From this group of artists came the Rashana Festivals. The Rashana Festival was the first annual summer festival for Lebanese open-air theater. The Basbous Brothers, Michel and Alfred, who were both sculptors, offered their property in the Rashana mountains to the Lebanese Theater Circle’s open-air Rashana Festivals. The festivals ran from 1961 till 1965.

The notions of place and space were central to Antoine Moultaka's theater, explaining why he chose the open-air theater for his works. The open-air was inspiring and conducive for experimentation. Most of Moultaka's plays, during the short-lived Rashana Festivals, were staged amidst the majestic sculptures of both Michel and Alfred Basbous. In preparation for his theater set design, Moultaka worked closely with Michel Basbous.

In 1964, Moultaka and his wife founded a drama department at the Fine Arts school at the Lebanese University. In 1967, Antoine Moultaka collaborated with Alfred Basbous to create the set design of Semsem, a play written in Arabic by Edouard Amin al-Boustani. The play was a subtle critique of a government authority. It was staged at the Achrafieh Theater, an accessible indoors space established by Moultaka and his colleagues in 1965. Unfortunately, the theater shut down in 1967, due to financial difficulties.

Jalal Khoury and Le Centre Universitaire d’Études Dramatiques

Transitioning from Moultaka's influence, another pivotal institution and a set of key figures emerge in the Lebanese theater scene. In 1961, a group of enthusiasts and theater lovers founded Le Centre Universitaire d’Études Dramatiques (CUED), a French Drama School at the University of École Superieure des Lettres in Beirut. Three people led the center: Jacques Metra, director of École Superieure des Lettres, playwright Georges Schéhadé, and theater director Anne-Marie Deshayes. Moreover, Jalal Khoury and Roger Assaf were central founding members of the CUED, as were directors Sharif Khaznadar and Yves Turkya. Others had a significant role as art critics, like Andres Bercoff and Joseph Tarrab. Tarrab, who had joined the group after two years from its establishment, participated in several plays as an actor and often as a director.

All the names mentioned above were progressives and experimental theater lovers, and had a radical and revolutionary approach to theater. They directed plays by European avant-garde playwrights such as Eugène Ionesco, Samuel Beckett, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, John Millington Synge, Carlo Goldoni, and Witold Gombrowicz. They were open to cultural, religious, and political diversity. Although most of the group members were Francophone, they welcomed Anglophones, such as Sharif Khaznadar, a graduate of the American University of Beirut.

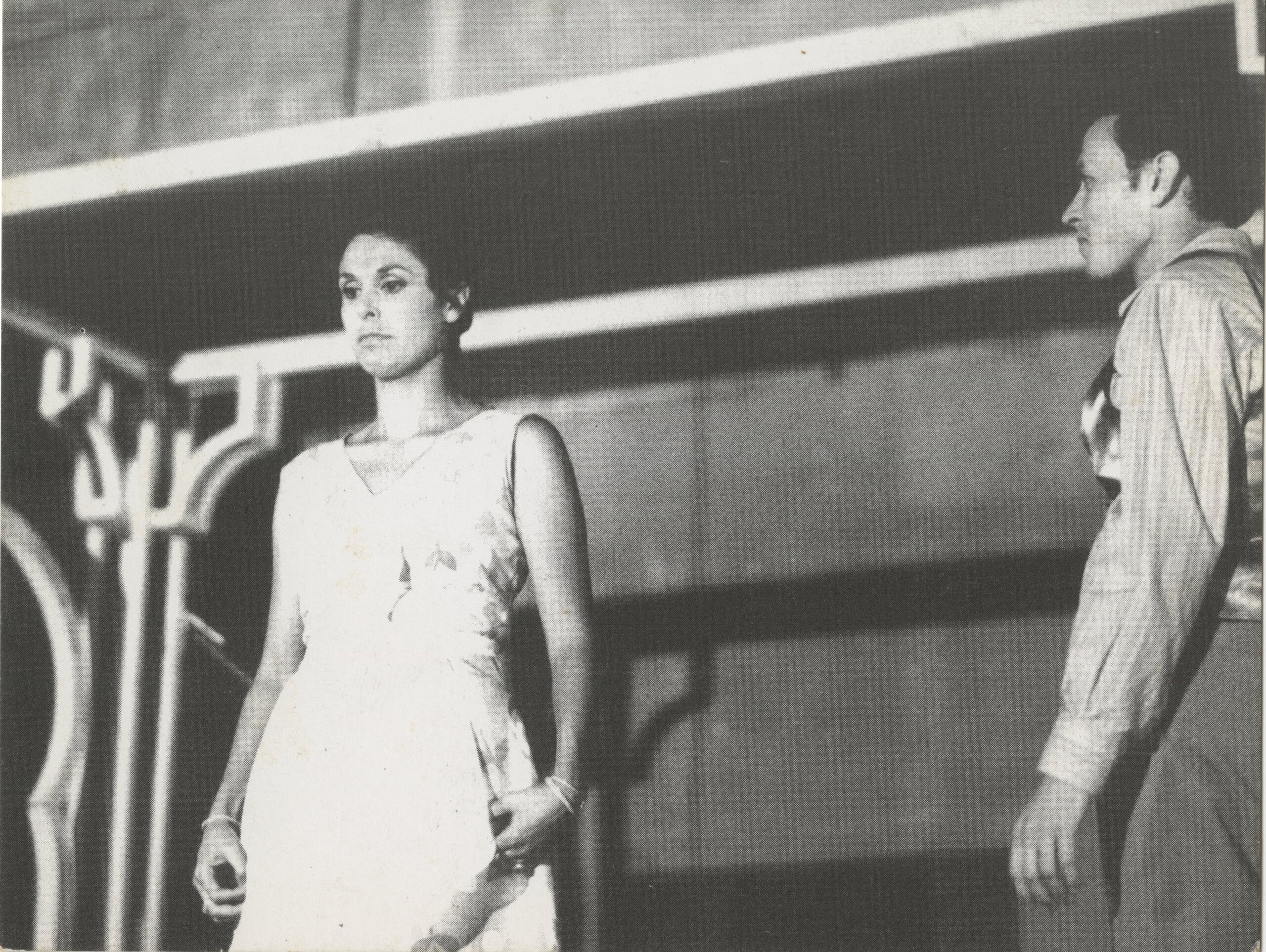

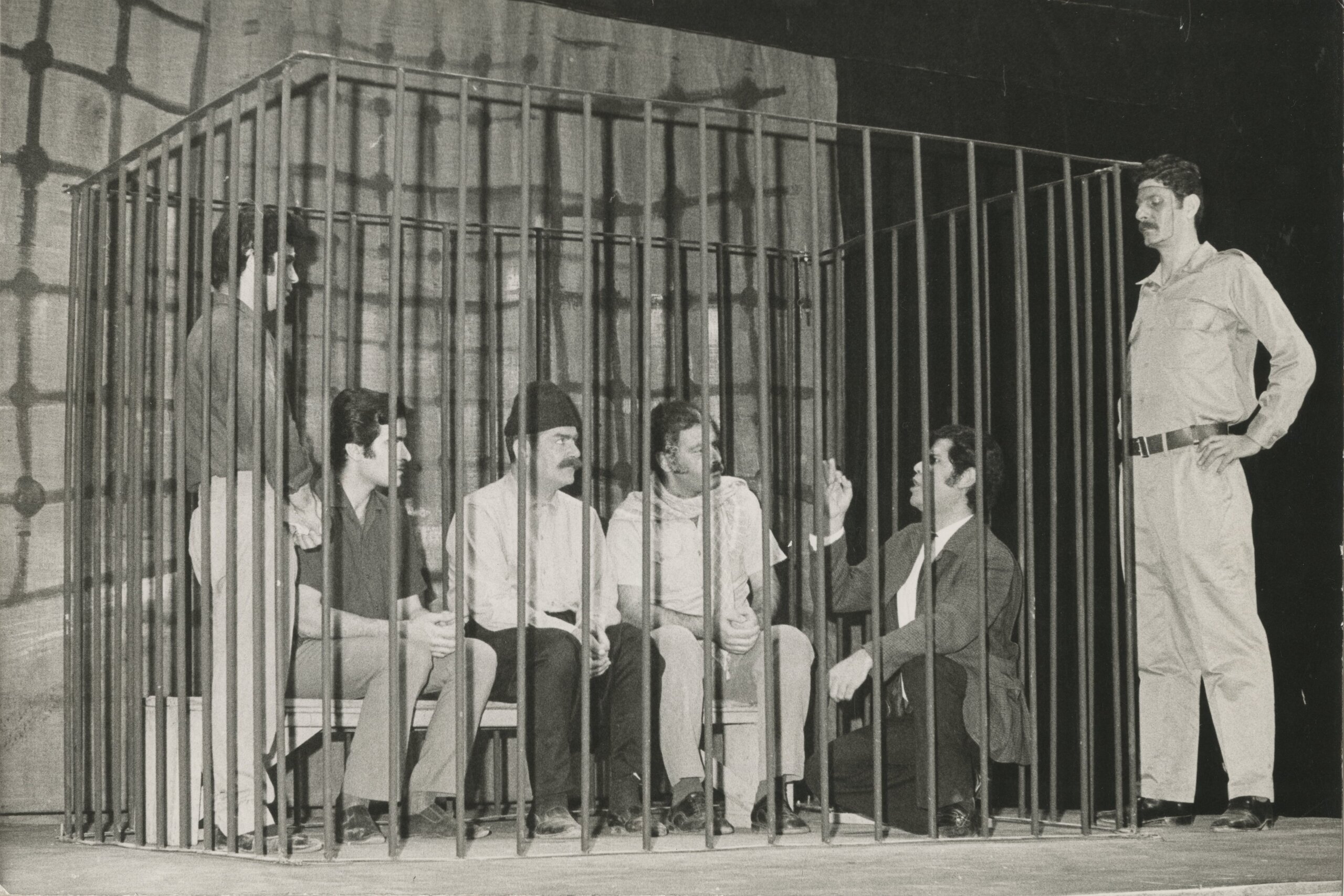

Playing a leading role in the development of theater in Lebanon, Jalal Khoury (1934-2018), was a self-taught dramatist and director. He adopted a provocative approach to theater. A fan of Brechtian theater, he favored plays that were concerned with moral dilemmas. For nearly a decade, Khoury drew from Bertlot Brecht’s epic theater plays. In 1964, he staged his first Brechtian play in French, Les Visions de Simone Machard (The Visions of Simon Machard) at the Gulbenkian Theater in Zkak el-Blat, in Beirut. In 1966, he presented his second Brechtian play, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, which was translated to Arabic. At this stage, Khoury, a well-trained writer for both Le Soir and L’Orient newspapers, started producing adaptations of modern European plays in Arabic. Ultimately, Khoury, a playwright sensitive to diction, ended up creating and writing his own scripts in Arabic.

Khoury, who was critical of classical theater and its extravagant setting, adopted a realistic and innovative approach to set design. He introduced simple furniture pieces and external elements such as paintings or written texts displayed as stage-backdrops. For that, Khoury asked his close friend Paul Guiragossian, a rising painter and a talented scenographer, to handle the set design of several of his plays. This included Les Visions de Simone Machard, in 1964, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, in 1966, Souk el-Fa’aleh in 1969, and Jeha fil Qoura al-Amamiyyah, which was staged at the temples of Baalbeck during the Baalbeck International Festivals in 1971.

Roger Assaf, Nidal Ashkar, and Mouhtaraf Beirut

While Khoury's influence was transformative, the vibrant theater scene of Lebanon was also shaped by dynamic talents like Roger Assaf. Assaf (b.1941) thrived for discovery and invention. His restless search for a genuine Lebanese Theater identity strongly reflected in his productions. After studying medicine for four years, Assaf shifted to theater and studied acting at L’Ecole Superieure d’Art Dramatiques du Théâtre National de Strasbourg from 1963 to 1965. Born to a French mother and a Lebanese father, his mother tongue was French. In 1967, Assaf committed to learning Arabic from scratch when he was offered to play a role in Jalal Khoury’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui. Assaf worked as an actor with Mounir Abou Debs, Antoine Moultaka, and other Lebanese directors before becoming a director himself.

In 1965, Roger Assaf co-founded the Beirut Theater and assumed the role of artistic director from the day of its inception till 1968. Dramatist Gabriel Boustani was the one who led to the establishment of the Beirut Theater in Ain el-Mreisseh. Boustani persuaded his friend, Said Sino, co-owner of Cinema Hilton, to render the place into a permanent theater – an indoor space much needed for all troupes in Beirut back then.

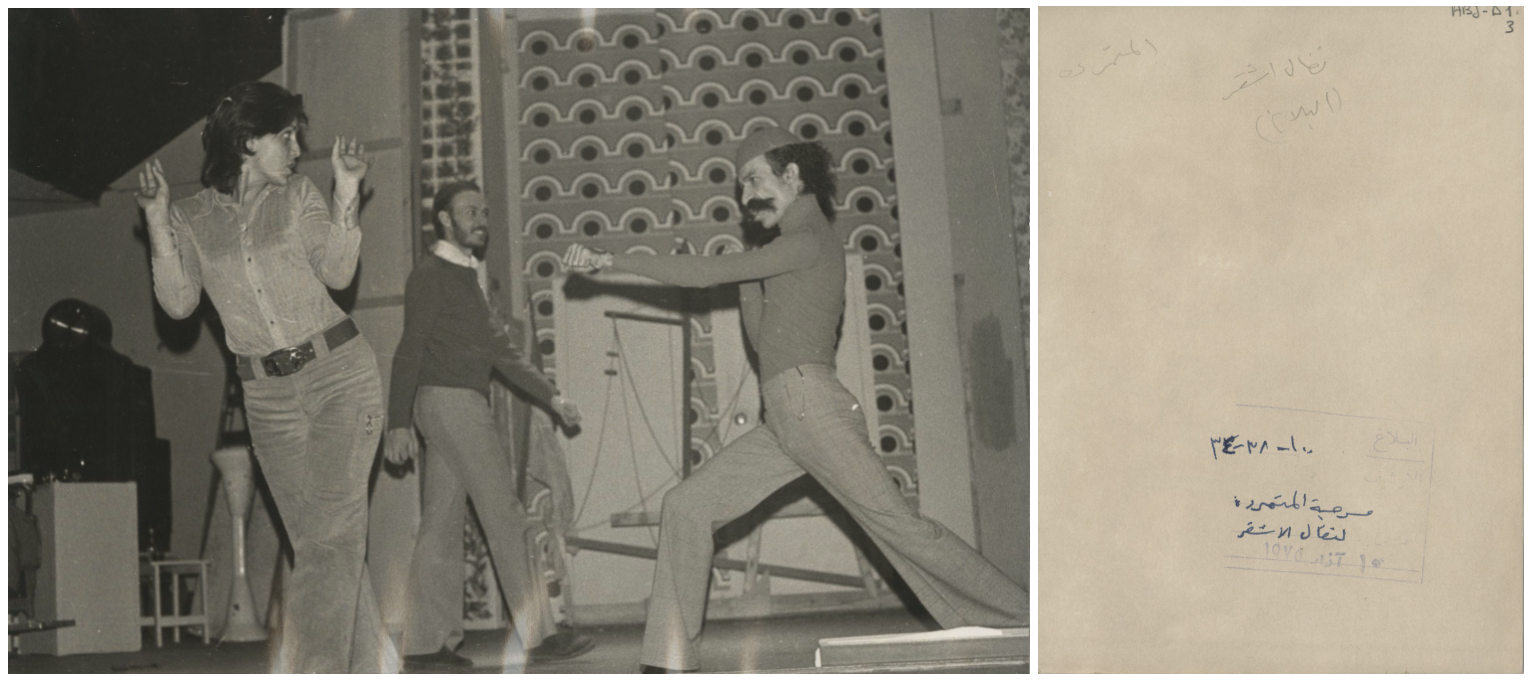

In 1968, actress and director Nidal Ashkar and Roger Assaf founded Mouhtaraf Beirut Lil Masrah (The Beirut Theater Workshop). Ashkar studied at the Royal Academy for Dramatic Art in London, and trained under late British director Joan Littlewood. As such, Ashkar drew the name of The Beirut Theater Workshop from Littlewood’s theater group known as Theatre Workshop, founded in 1945 for the working-class audiences. Similarly, Ashkar and Assaf wanted theater to be an extension of popular culture and society. They coached actors to engage with the audience and to challenge authority. In line with their leftist ideals, they addressed political concerns by adopting narratives that the popular masses understood. In 1969, Roger Assaf and Nidal Ashkar created, directed, and performed in one of the most controversial plays of the time: Majdaloun written by Henry Hamati. The play encouraged domestic revolution and addressed the Palestinian armed presence in South Lebanon – a direct result of the Israeli occupation of Palestine. Three days after its debut at The Beirut Theater, the play was censored, and the production was interrupted by the Lebanese military and Lebanese general security. Assaf, Ashkar, and the actors walked with the audience to Hamra street and resumed the performance at a famous intellectual hangout cafe, known as the Horseshoe.

This interactive spirit between audience and actors reached its climax in Idrab al-Haramieh, a play written by dramatist Ousama Aref, and directed by Assaf and Ashkar in 1970. In a highly creative setting, the play was staged at the ballroom of the Hotel Normandy, in Beirut. To amass such a vast space with creative stage backdrops, Roger Assaf and Nidal Ashkar collaborated with their dear friend and painter, Paul Guiragossian, who produced more than forty paintings for this occasion. Later, in 1979, Roger Assaf and his wife, actress Hanane Hajj-Ali, established Al-Hakawati theater to revive classical Arabic theater traditions.

David Kurani, Theater at AUB, and the Berytus Theater Ensemble

Building on the momentum set by influential figures, another pivotal institution in the Lebanese theater scene was the American University of Beirut (AUB). Since the 1950s, professors and students at AUB have been active theater-makers. Key people who developed the theater at this institution were Nabil Ashkar, David Kurani, and Peter Shbay’aa. Nabil Ashkar was a member of one of AUB’s earliest theater groups, the English Drama Players, founded by director Christopher Henry Oldham Scaife. Nabil Ashkar and his colleagues established the New Theater Group and, between 1951 and 1956, produced plays in English, French, and Russian. In 1958, with the help of the Anglophone community in Lebanon and abroad, the American Repertoire Theater (ART) was founded. They staged their plays at West Hall in AUB, the Beirut Theater, and Gulbenkian Theater in Beirut. At times, they even showed at the Baalbeck International Festivals.

A crucial figure in AUB’s evolution of theater in Lebanon was David Kurani. He studied Fine Arts at AUB, and theater at Bristol Old Vic Theater School in London. Kurani is a painter, actor, playwright, and director. He oversaw the development of the AUB Drama Club, founded in the 1960s by English director Joy Curnow. In 1968, David Kurani, Peter Shbay'aa, and Krikor Satamian established the Berytus Theater Ensemble, which lasted till 1972. They produced plays by classical playwrights (Sophocles, and Shakespeare), Russian playwrights (Alexander Ostrovsky and Anton Chekhov), and modernist Bertlot Brecht. As part of the Berytus Theater Ensemble, Kurani’s first play to direct was Shakespeare's The Twelfth Knight. The next was The Liar by Goldoni.

The multitalented David Kurani was not only a theater maker but also a set designer. He designed the sets for over thirty-six stages, the earliest of which was that of Oedipus The King by Sophocles. Through his diverse talents and multifaceted contributions, David Kurani truly left an indelible mark on the Lebanese theater scene, exemplifying the fusion of classical and modern elements in his productions.

The journey of Lebanese theater is a testament to the dynamic interplay between heritage, global influences, and innovative creativity. Stemming from the broader canvas of Arab theatrical renaissance at the turn of the 20th century, Lebanese theater has carved its distinct narrative. By re-contextualizing Western productions and integrating them with Arabic sensibilities, pioneers laid the groundwork for an enriching era of Arab theater. This momentum found its peak in the 1960s in Beirut, a vibrant hub of multilingual theatrical expressions. The significance of this period, especially post-1965, marked a transformative phase for Lebanese theater. With the opening of key theaters and the establishment of specialized institutions, Lebanese theater matured and flourished.

In conclusion, the evolution of Lebanese theater is a mirror to the broader socio-cultural shifts and artistic currents within the Arab world and beyond. From its formative years, shaped by the region's collective theatrical renaissance, to its maturation, it reflects a story of resilience, adaptation, and innovation. As we celebrate the legacies of its pioneers and acknowledge its rich tapestry of influences, the journey of Lebanese theater stands as a beacon of cultural evolution and an inspiration for future artistic endeavors.

Sources

Alabdullah, Abdulaziz H. “Original or Western Imitation: The Case of Arab Theater.” Journal of Literature and Art Studies 4, no. 9 (2014). https://doi.org/10.17265/2159-5836/2014.09.008.

Assaf, Roger. Les multiples naissances du Theater libanais. Accessed September 6, 2020. https://alba.edu.lb/AR/FR/thea... News, Lebanon News, Middle East News & World News. Accessed September 6, 2020. https://www.dailystar.com.lb/P... of Drama in Arabic Literature.” Accessed September 6, 2020. http://ijmas.com/upcomingissue/14.04.2016.pdf.

“Home.” Imaginary Theater. Accessed September 6, 2020. http://www.imaginarytheater.or... AMERICAN UNIVERSITY.” Accessed September 6, 2020. https://laur.lau.edu.lb:8443/x... AMERICAN UNIVERSITY.” Accessed September 6, 2020. https://laur.lau.edu.lb:8443/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10725/6551/Mira_Teeny_Thesis_Redacted.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Maleh, Ghassan. “The Birth of Modern Arab Theater.” Questia. Accessed September 7, 2020. https://www.questia.com/magazi... - De La Sorbonne Au Festival De Freikeh, plus De Cinquante Ans De Passion Pour Un Théâtre Total Mounir Abou Debs En ‘État De Présence’ (Photos).” L'Orient-Le Jour, September 14, 2004. https://www.lorientlejour.com/article/481739/RENCONTRE_-_De_la_Sorbonne_au_Festival_de_Freikeh,_plus_de_cinquante_ans_de_passion_pour_un…

Saeed, Ahmoud. “Khalida Said Documents Golden Period of Lebanese Theater.” Khalida Said Documents Golden Period of Lebanese Theater | Al Jadid. Accessed September 7, 2020. https://www.aljadid.com/content/khalida-said-documents-golden-period-lebanese-theater.

Saiid, Khalida. Al-Haraka-Al-Massrahiya-Fi-Libnan. Baalbek Festivals Committee. Arayia, Baabda: Catholic Publishers, 1998.

Saiid, Khalida. Al-Haraka-Al-Massrahiya-Fi-Libnan. Baalbek Festivals Committee. Arayia, Baabda : Catholic Publishers, 1998.

Teeny, Mira. “Origins of Arabic Theater: A Transcultural Theatrical Relation Between Arabic and European Theater.” Thesis, LAU, 2017.

Teeny, Mira. “Origins of Arabic Theater: A Transcultural Theatrical Relation Between Arabic and European Theater.” Thesis, LAU, 2017.

“Theater and Performance Landscapes in Lebanon.” PrintFriendly & PDF. Accessed September 6, 2020. https://www.printfriendly.com/... in the Arab world. Accessed September 6, 2020. https://al-bab.com/albab-orig/albab/arab/visual/theater.htm.

الدين روان عز. “متى كان المسرح جزءاً من النسيج المدني لبيروت؟.” Accessed September 6, 2020. https://al-akhbar.com/Literature_Arts/247064.

“-.” Accessed September 6, 2020. http://www.ahewar.org/debat/show.art.asp?aid=275227.

Comments on The Evolution of Lebanese Theater: Tracing Roots and Charting Progression